Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Plan C: How Makerspaces are Providing a Stopgap for COVID-19 Supply Shortages

Mar 30, 2020

One of the participants in the Think Global Make Local product development workshop, sponsored by our Cambodia Development Innovations project in 2016, created a design for a toy called Doy Doy. With Doy Doy’s silicone straws and plastic connectors, kids can build complex structures. The product has gone on to achieve modest commercial success locally. I found Doy Doy instructive because of the way its creator, Em Chanrithykol, ended up manufacturing the toy’s plastic connectors. Because of a lack of local injection-molding capacity and administrative barriers to importing parts made by contract manufacturers outside of Cambodia, Chanrithykol turned to a less traditional method: He contracted a local firm to churn out the parts on a battery of 3D printers.

3D printing is slow, expensive, and inefficient. It is great for small runs of one-off items or prototypes, but it is a terrible way to mass manufacture a product. But the lesson of Doy Doy is that a bad way to mass manufacture a product can still be better than having no way to mass manufacture a product. This is why I am currently manufacturing personal protective face shields for Baltimore-area hospitals in my basement.

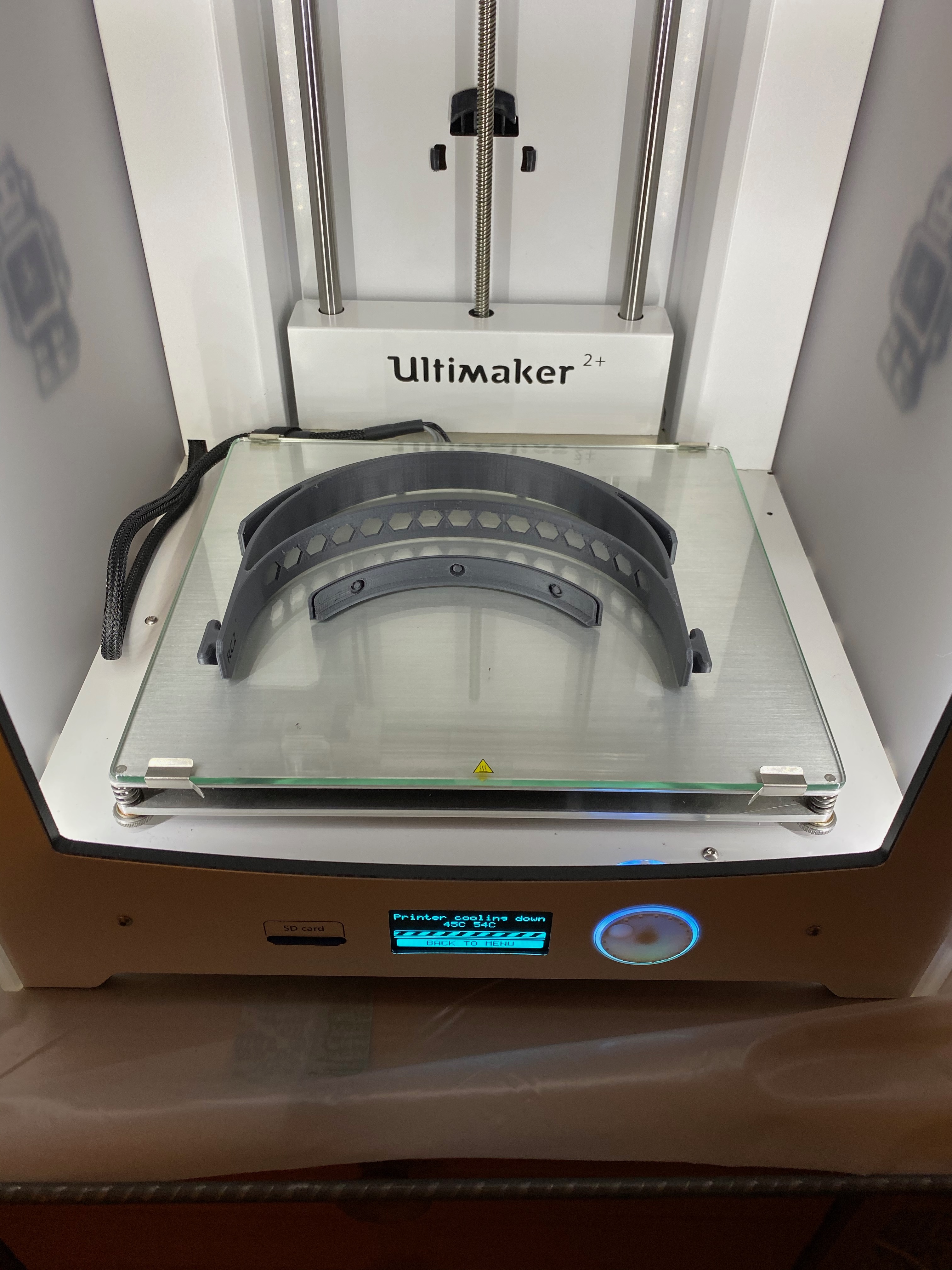

DAI's 3D printer in author's home. Photo courtesy of author.

As I described in my last post, the maker community has been energized around producing goods that face critical shortages, such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and ventilators. But getting these products applied in clinical settings requires much more than printing a clever design. DAI’s printer—temporarily relocated to my basement work-from-home space—is producing parts for Open Works, a Baltimore makerspace, which has addressed some of these issues. Here is how it works:

- Design Validation: Few goods have more stringent criteria for validation than those for medical applications. Design, build quality, safety, and sterility are among the criteria, and clinical operations—and their lawyers—will generally insist on items built to the highest standards in these areas.

The face shield design we are currently producing for Open Works was developed by Prusa Research, a Czech printer manufacturer founded by Josef Prusa, who commands a great deal of respect in the hardware community. The design was prototyped and iterated in collaboration with the Czech Ministry of Health, which gives the design some credibility, though obviously far short of an official certification.

-

Production: As noted, 3D printing is not a volume-oriented process. Working around the clock, the DAI printer can produce four to five units per day. So Open Works is crowdsourcing the process, working with makers around Maryland and the region to produce parts. As of this writing, DAI is among 68 makers actively producing parts for the Open Works network.

-

Quality Control: Build quality will vary from printer to printer, and some cheap feedstock—the material you put into the printer—can also degrade quality. Open Works has specified the settings that should be used by those supporting the development of some of these parts. These standardized settings are the biggest factor determining quality. But it is difficult to verify that crowdsourced producers have correctly dialed in these settings.

The Open Works project also has a set of disinfection protocols intended to ensure reasonably sterile parts, but they are quite basic, certainly fall well short of being medically sterile, and are also difficult to verify.

- Manufacturing Process Control: In more placid times, the Baltimore organization We The Builders coordinated the distributed printing of sculptures for events. DAI has previously participated in We The Builders projects, such as printing a number of pieces of the crowdsourced Nefertiti statue at the Fab15 conference in Egypt this past summer, for example. The software that We The Builders created around this task has been cleverly repurposed for Open Works’ PPE effort, assigning parts to makers and tracking them through the process.

Image of 3D-printed mask on display in Egypt.

- Customers: Finally, what the Open Works project has that many of the efforts online lack is a relationship with customers who want the printed PPE. The Baltimore-area facilities that Open Works is working with will likely not be giving these PPE to doctors and nurses, but assigning them to other staff to free up more traditional units for frontline clinical staff. Other, similar efforts from organizations around the country, including Nova Labs in Reston, Virginia, and NextFab in Philadelphia, also have identified pipelines to local users in those areas.

The truth is, 3D printing is a terrible way to produce medical equipment at scale, but it is still better than having no way to produce medical equipment at all.

This effort to crowdsource the production of face shields, cloth masks, and even ventilators, is being labeled Plan C. It is a weak stopgap while traditional high-volume supply chains gear up to provide the necessary equipment to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. I fully expect that those supplies will become available quickly. But when we inevitably rethink supply chains in the wake of this crisis, the lessons learned during Plan C may well come into their own.