Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

COVID-19 Data Analysis, Part 3: Rethinking the Global Health Security Index

This post is one of a series of posts on COVID-19 Data.

Apr 16, 2020

The next installment in our COVID-19 analysis series connects the dots between the datasets we have explored in our previous posts and brings in a new dataset that came to our attention over the past couple of weeks. In this paper, we look at the relationship between country scores from the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI)’s Global Health Security Index and levels of response by country governments measured using the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. You can read more about our initial exploratory analysis of the Global Health Security Index here in our previous blog post. Oxford University has provided an initial report of its data on its website.

Key Findings

-

Countries that score lower in the Global Health Security Index Response category have mobilized more quickly against the spread of COVID-19 than countries that score higher.

-

For every additional point achieved on the Global Health Security Index Response score, countries take an additional ~0.60 days to act.

If you have been following our posts, you may have noticed that we have not included COVID-19 case data in our work. This has been intentional. Our analyses compare countries around the world—each of these countries, however, have different methods and resources to measure COVID-19 cases and deaths. In the United States, there is a severe shortage of tests for the virus and, as a result, the reported case numbers are understating the real case numbers. Different countries are also measuring deaths differently. Deaths in some countries are counted as COVID-19 deaths if the patient died from a health condition unrelated to COVID-19 (a heart attack, for example) but was diagnosed with the virus. Some COVID-19 deaths are also never counted because of the testing shortage we just mentioned. Officially, a person cannot die from COVID-19 if they never had it. We have chosen to look at other data because of these issues.

Data

This analysis uses data from two datasets: NTI’s Global Health Security Index and Oxford University’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT). The Global Health Security Index is a comprehensive assessment of global health security capabilities for country-level preparedness and response. It is made up of multiple categories, one of which—Response—attempts to capture country-level capacity to respond to global health outbreaks, like whether a country has a national public health preparedness and response plan. The OxCGRT measures actual country response by tracking 13 different indicators. These indicators include closing public transportation, cancelling public events, and enacting international travel restrictions. The tracker uses these measures to calculate a cumulative response score known as the Stringency Index. Specific details on how this score is calculated can be found here.

Hypothesis

The Global Health Security Index Response score is meant to measure “rapid response to, and mitigation of, the spread of an epidemic” but does not factor in time. We believe that there may be different relationships between actual government response and country response scores at different milestones of the pandemic. Here, we test our hypothesis that countries that score higher in the Response category will respond more quickly to an epidemic or pandemic than those that score lower.

Analysis

To measure the speed of government response, we calculated the amount of time of first action by measuring the number of days between a country’s first confirmed case of COVID-19 and its first action taken. We define the date of first action as the date that a country has taken any measures, regardless of what those measures are. For example, a country that takes first action by restricting international travel on January 1 has the same date of first action as a country that takes first action by closing schools on January 1.

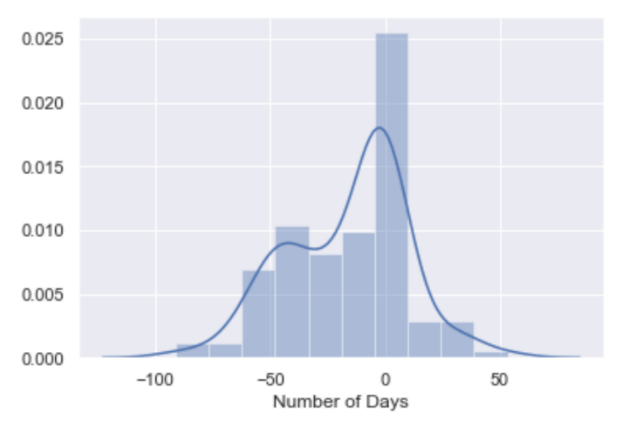

In the histogram below, we can see that the number of days it took countries to act is distributed relatively normally, with a peak and center around 0 days. This means that of the 120 countries recorded in our dataset, most mobilized on the same day that their first case of COVID-19 was confirmed. The number of days to first action ranges from 91 days prior (Botswana) to 53 days after (Thailand) the country’s first confirmed case.

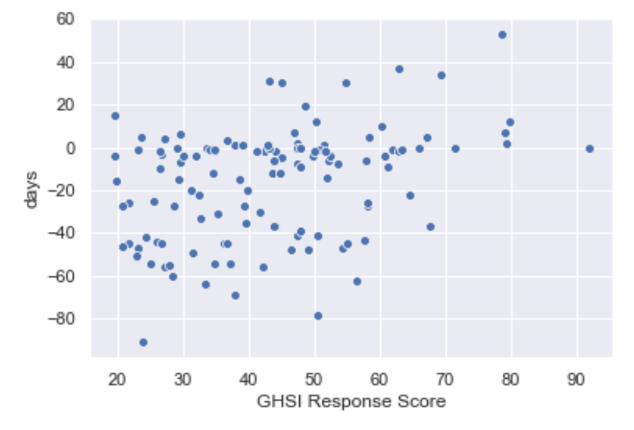

Next, we compared the Response score of the Global Health Security Index to the number of days to first action. Surprisingly, we can see a slight positive correlation between the two measures, seen in the scatter plot below.

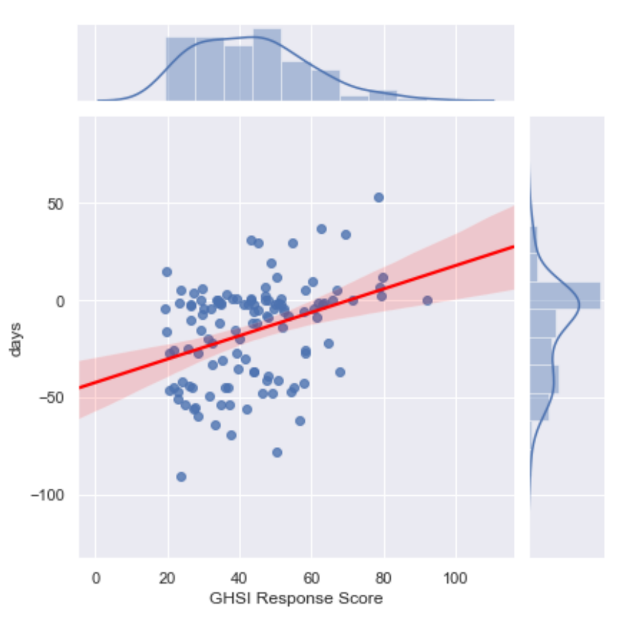

To put this another way, countries that scored lower in the Response category implemented measures more quickly than those that scored higher on the index. We conducted a simple linear regression analysis to determine the strength of this relationship. The plot below shows our linear model plotted with our data, in addition to the distributions of our independent and dependent variables.

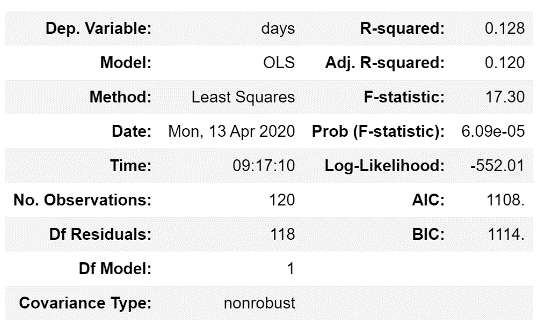

From our model output below, we can see that this model explains a small percentage (about 12.8 percent) of the variance in our data. However, this is not extremely surprising—human behavior is often unreliable and difficult to predict. We also included only one variable in this model and believe that additional variables can be used to explain speed of response that are not included in the Response score—possibly including government type (eg. democratic vs autocratic) and historical experience with pandemics and epidemics. We will discuss these variables in future blog posts.

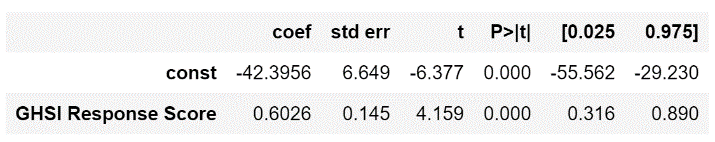

Our regression co-efficient provides us with a specific measure of this relationship. This value (0.6026) indicates that for every additional point on the Global Health Security Index Response score, you can expect the number of days between first case and first action to increase by an average of 0.60 days. Our p-value, ~0.00, indicates that this relationship is statistically significant—that is, that the differences in the Global Health Security Index Response score are associated with differences in the speed of action.

Conclusion

Ultimately, our model has shown us that this assessment for evaluating country response capacity for a pandemic is not indicative of the speed of actual response, as measured by the number of days between a country’s first confirmed COVID-19 case and its first action. In this pandemic, countries that score lower on the index have acted more quickly than countries that score higher. To be clear, this analysis does not invalidate the Global Health Security Index score for Response, but rather identifies a gap in measurement. While certain countries may have, for example, robust response plans in place, there is no measure in the index to evaluate whether these plans will be enacted quickly or properly.

In addition to this index, we believe that there are many other factors that contribute to a country’s robust and swift response. Strong leadership, for example, that takes quick and decisive action may enable countries to overcome some structural barriers that are measured in the Global Health Security Index. Weak leadership, on the other hand, may not use all a country’s resources and therefore weaken response. From our analysis, we can gain some hope for what is to come. Various global health experts and media outlets have highlighted African countries, many which score low on the Global Health Security Index, that will likely experience high case numbers and deaths due to COVID-19 based on a severe lack of resources. However, the quick action that many African leaders and countries have already taken to contain the virus may indicate that they may not be as severely impacted as some may think. This is only one factor that we will continue to explore in future analyses.

We note that this analysis examines only speed of response and does not explore what types of action was taken or whether these actions have proven successful. This analysis does not consider quality of response and is not indicative of response outcomes. Just because a country acted more swiftly does not mean that they will experience fewer (or greater) COVID-19 cases. We also looked only at overall response scores and did not compare the specific indicators that make up these cumulative scores. We will continue to dig into this data to pull out more insights that will help the global health community better understand and act against this pandemic.