Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

COVID-19 Data Analysis, Part 2: Health Capacity and Preparedness

This post is one of a series of posts on COVID-19 Data.

Apr 2, 2020

- This analysis is Part 2 of a series on known risk factors associated with COVID-19. We aim to use publicly available data sets to identify national and subnational populations most at risk for infection and case fatality. The analysis will be updated as we receive additional data.*

The observed cross-country differences in the number of tests and infection and mortality rates as it relates to COVID-19 have provided a source for theorizing about factors that may lead to different outcomes across the globe. The first part of this series focused on the demographic and behavioral factors at the country-level that may cause increased stress on health systems in responding to COVID-19. Although demographic and behavioral factors clearly are important pieces of the puzzle in explaining the degree of risk countries face, they also bring into question the level of preparedness and capacity of countries in dealing with pandemics.

The post examines health capacity and preparedness at the country level to comparatively assess the resources available in combating COVID-19. First, we will focus on general health systems capacity, assessed by reviewing health input indicators such as hospital beds, doctors, and nurses, per 10,000 inhabitants. The second part addresses the concept of preparedness and response to outbreaks, giving particular emphasis to the Global Health Security Index.

Structural Capacity

Defining system capacity for any realm of public policy is difficult given the numerous actors and the multiple levels of government involved. This is particularly true concerning health systems, which incorporate a complex set of issues and dimensions of governance. As it relates to comparative assessment of country health systems, the structural capacity of countries refers to the informational, organizational, physical, human, and fiscal resources available.

While there are many measures of health system capacity, the most immediate ones as they relate to assessing the risk countries face in the COVID-19 pandemic, and for which there is systemic and complete data, are hospital beds, doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 inhabitants, as collected by the World Health Organization.

Factor 1: Hospital Beds

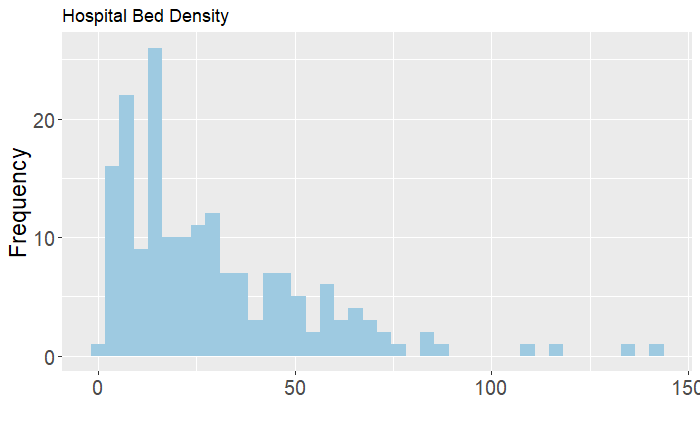

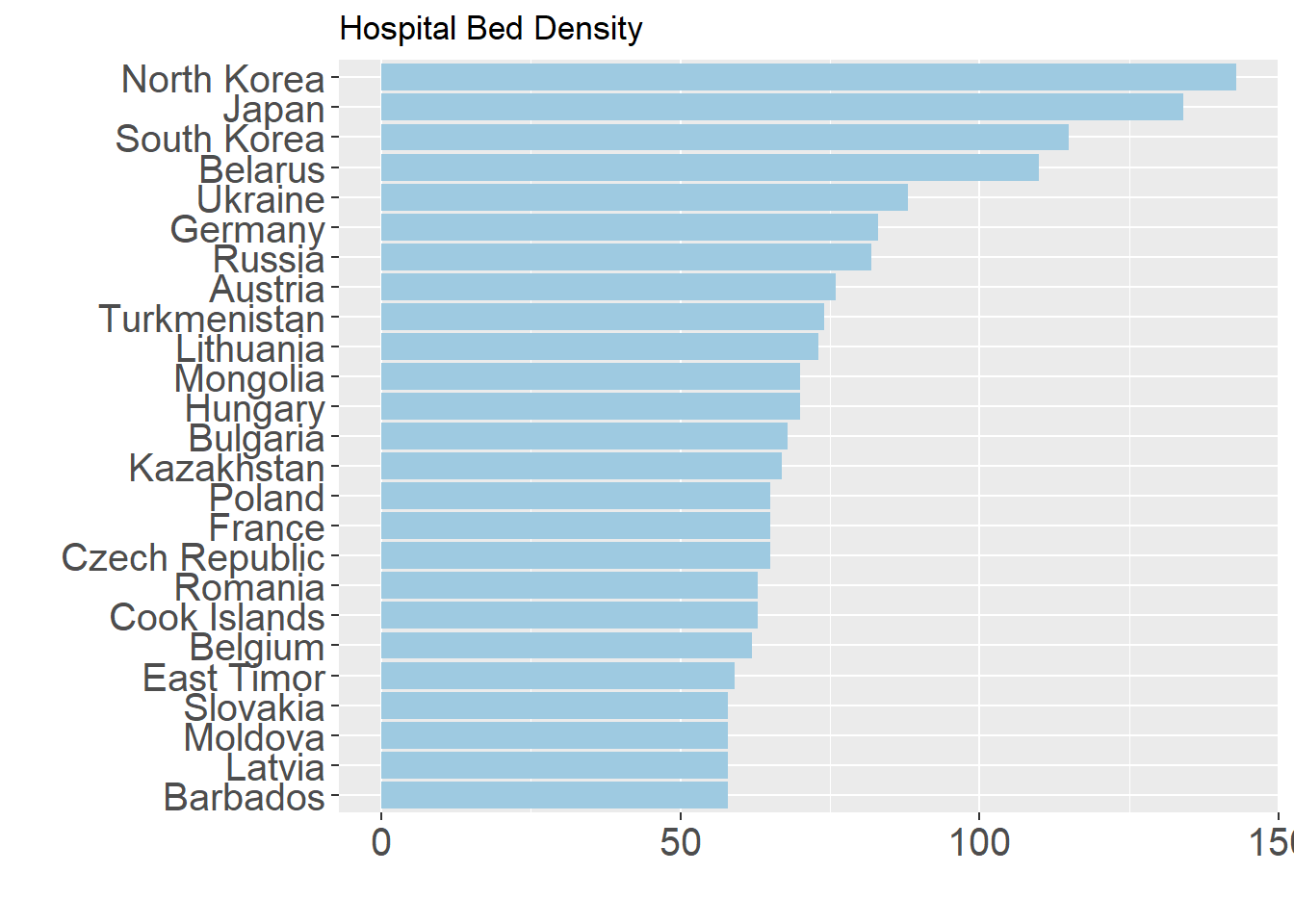

Much attention has been paid to the capacity of countries and regions to adequately provide attention to severe and critical cases of COVID-19. While the sheer numbers will likely overwhelm every health system in the world, the number of hospital beds serves as an important proxy to assess capacity to provide care to patients.

The most recent data from the World Health Organization suggests significant path dependency and political legacy in hospital bed density. In total, 17 of the top 25 countries are former Soviet republics or allied countries, and one country (Germany) that reunified after the fall of the Soviet Union. Beyond these, the data is naturally more heavily skewed towards countries with lower population totals such as Timor-Leste, the Cook Islands, and Barbados, along with several higher-income countries, including Austria, France, Japan, and South Korea.

It is worth noting that this indicator only tells us one small part of the larger equation in assessing health system capacity. As greater emphasis in recent years has been placed on more effective use of existing resources and less reliance on secondary care, hospital bed density rates have been declining in many of these top countries and many of the former Soviet republics. This indicator also does not take into account the capacity of countries to establish makeshift hospitals and thereby increasing the overall availability during times of high stress. Despite these shifts in the focus of public health system strengthening, hospital beds are a crucial resource in providing care in response to COVID-19 as the number of severe and critical cases inundate health systems. The immediate availability of these resources will play an important part in the battle against COVID-19.

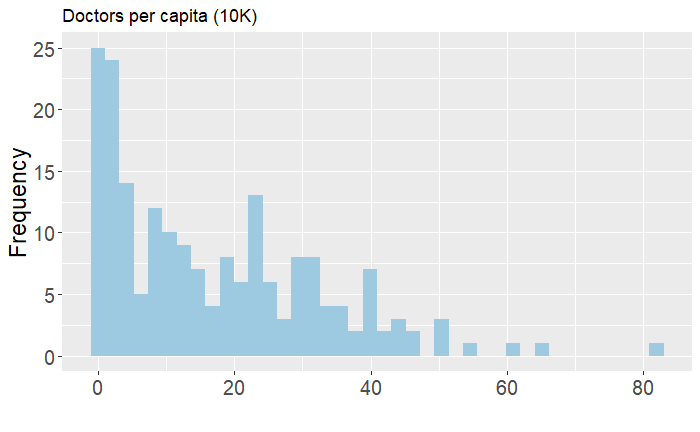

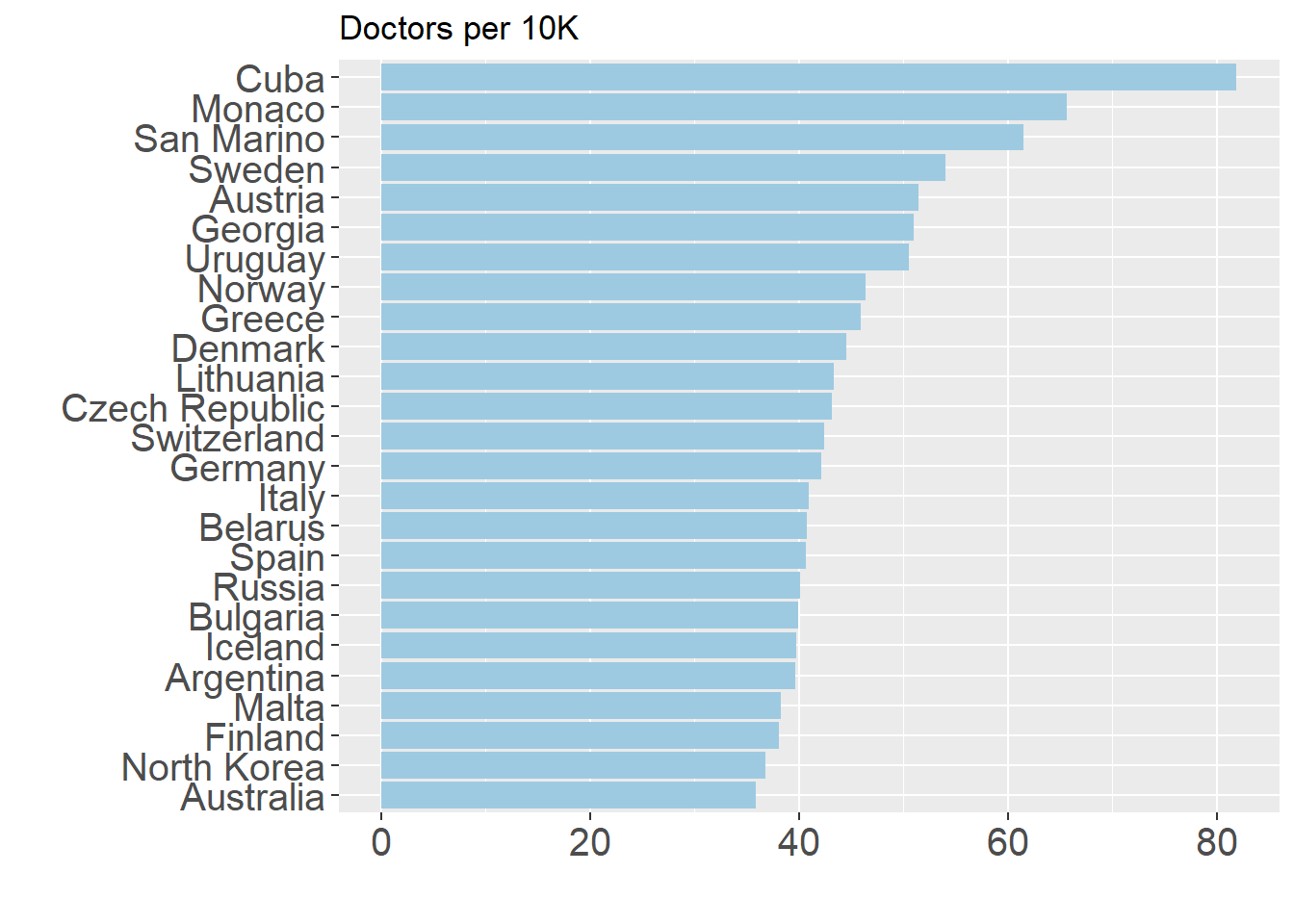

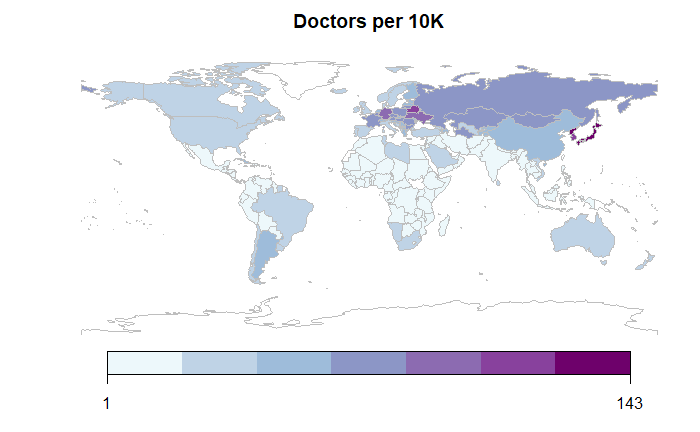

Factor 2: Medical Doctors

The importance of doctors per capita in measuring health system capacity is quite intuitive. Even in normal times, low supply of doctors directly implies limited access to care and higher overall prices, problems that are exacerbated in situations of disease outbreak. Unfortunately, 30 percent of countries have a supply of doctors below the recommended number of 10 per 10,000 people. The histogram below shows a similar trend to hospital bed density, with few outliers and a heavily left-skewed distribution.

Similar to hospital bed density, the doctors indicator also shows a lasting legacy of communist and socialist rule, with the presence of Cuba and Russia, amongst others. Beyond these, countries with strong historical emphases on social protection systems unsurprisingly figure heavily in this graph, such as Scandinavian countries and Argentina and Uruguay. It is worth noting that the Mediterranean countries, such as Italy and Spain, have suffered greatly due to COVID-19 figure highly on this list.

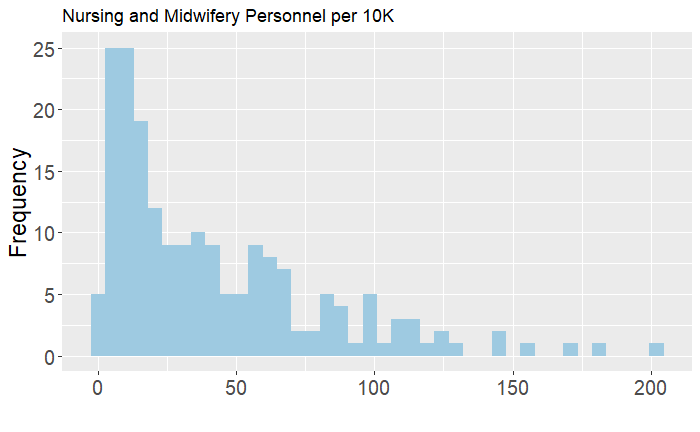

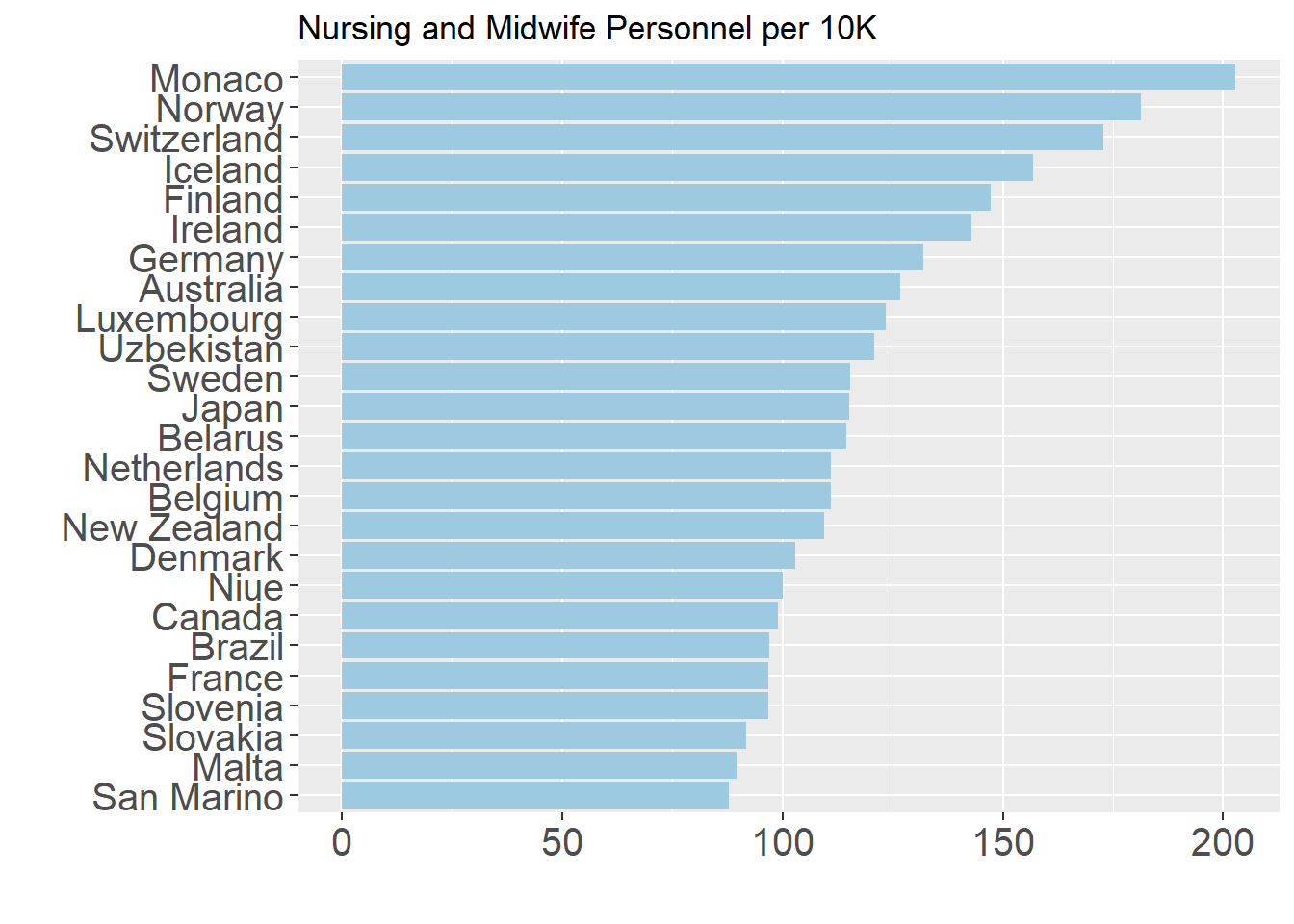

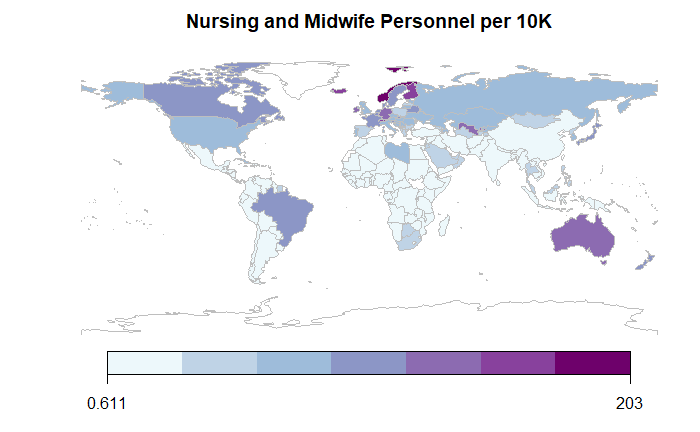

Factor 3: Nursing and Midwifery

Nurses are a critical part of any health system and historically have played a vital role during pandemics. The role of nurses in pandemics has also been transformed in terms of providing care, monitoring cases, administering and educating on use of medication, and serving as communicators between patients, doctors, and administrators.

In more recent times, as countries have moved towards lower-cost solutions and greater focus on preventive and primary care, the number of nurses per capita has increased for many countries, particularly in the low- to middle-income ones. While these numbers in time-series have increased, the top countries in per capita terms are quite similar to countries emphasized previously, although there are relatively fewer post-Soviet republics highlighted here.

Preparedness

While the principal elements of structural capacity provide a solid foundation in response to pandemics, there are many other factors in which countries must develop know-how and resources to effectively respond to infectious disease outbreaks. The Global Health Security (GHS) Index—developed by the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHU), and Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)—is a comprehensive assessment of health security and capabilities in preventing, detecting, and responding to public health emergencies, which includes 195 countries. Given the emphasis on information being publicly available, the index scores favor countries that are more transparent in providing data and evidence of processes.

On the whole, the GHS Index makes clear that preparedness can be improved for every country. As the 2019 report states, “National health security is fundamentally weak around the world… The average overall GHS Index score among all 195 countries evaluated is 40.2 of a possible score of 100. Among the 60 high-income countries, the average GHS Index score is 51.9. In addition, 116 high- and middle-income countries do not score above 50.” There are six indices related to: prevention, detection, response, health, norms, and risk. These categories are collectively based on 35 indicators, 85 sub indicators, and 140 questions. While we include each of these six principal scores in the dataset highlighted above, this post focuses on the parts that will be most important in determining health system challenges and successes going forward.

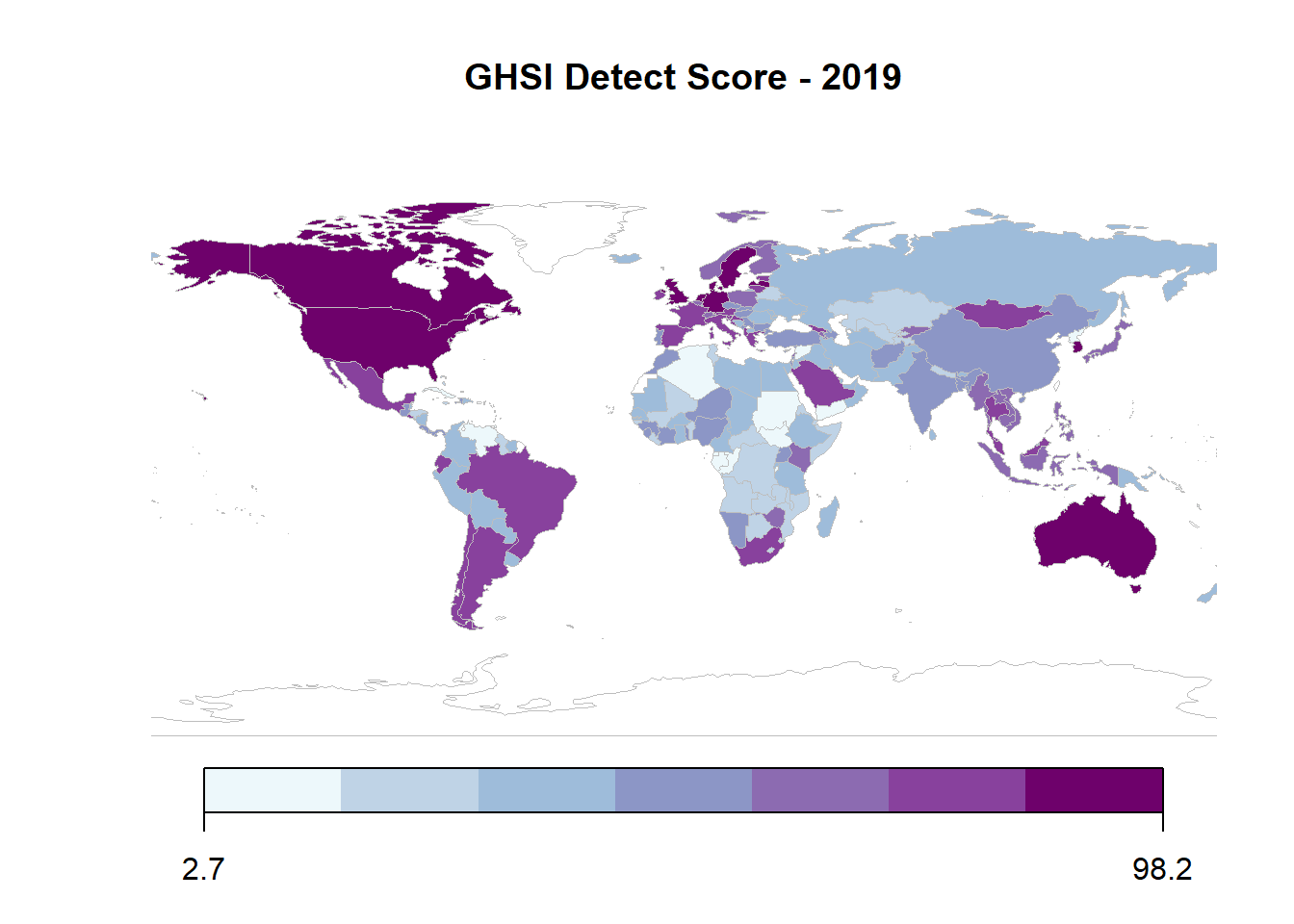

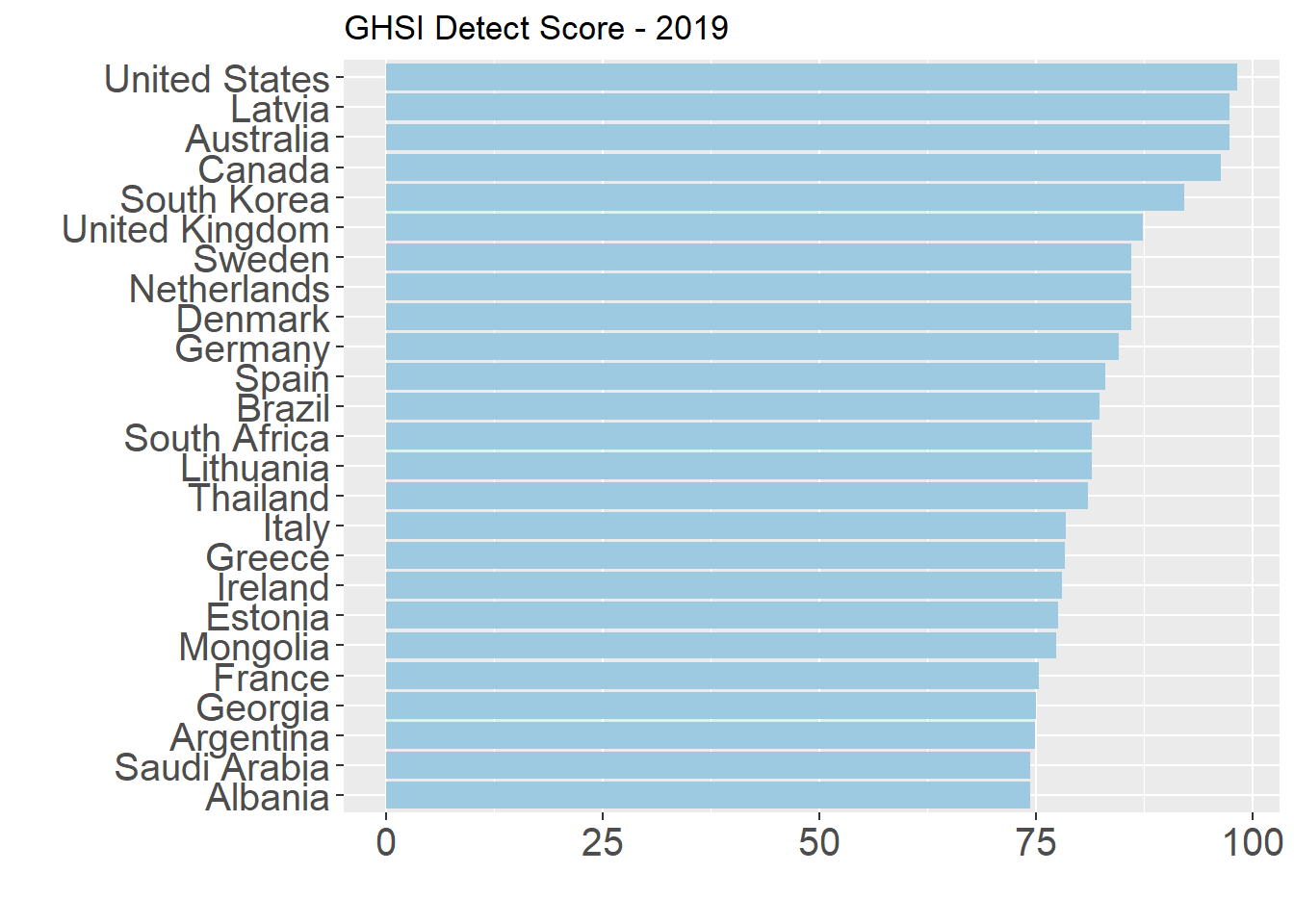

Factor 4: Detection and Reporting Testing

As COVID-19 has made evident, capacity to produce the number of tests needed and then monitor cases allows governments to more efficiently allocate resources to where they are most needed, reduce hospital overload, and prevent resorting to more extreme measures of lockdowns and disruption of economic and social life.

The Detection and Reporting score assesses country capacity based on laboratory systems, the presence of electronic real-time surveillance and reporting, epidemiological workforce, and data integration between human, animal, and environmental health sectors. While the average score on this metrics is 41.9, no single country scored a complete 100 on the real-time surveillance and reporting indicator, which is particularly relevant to the current moment.

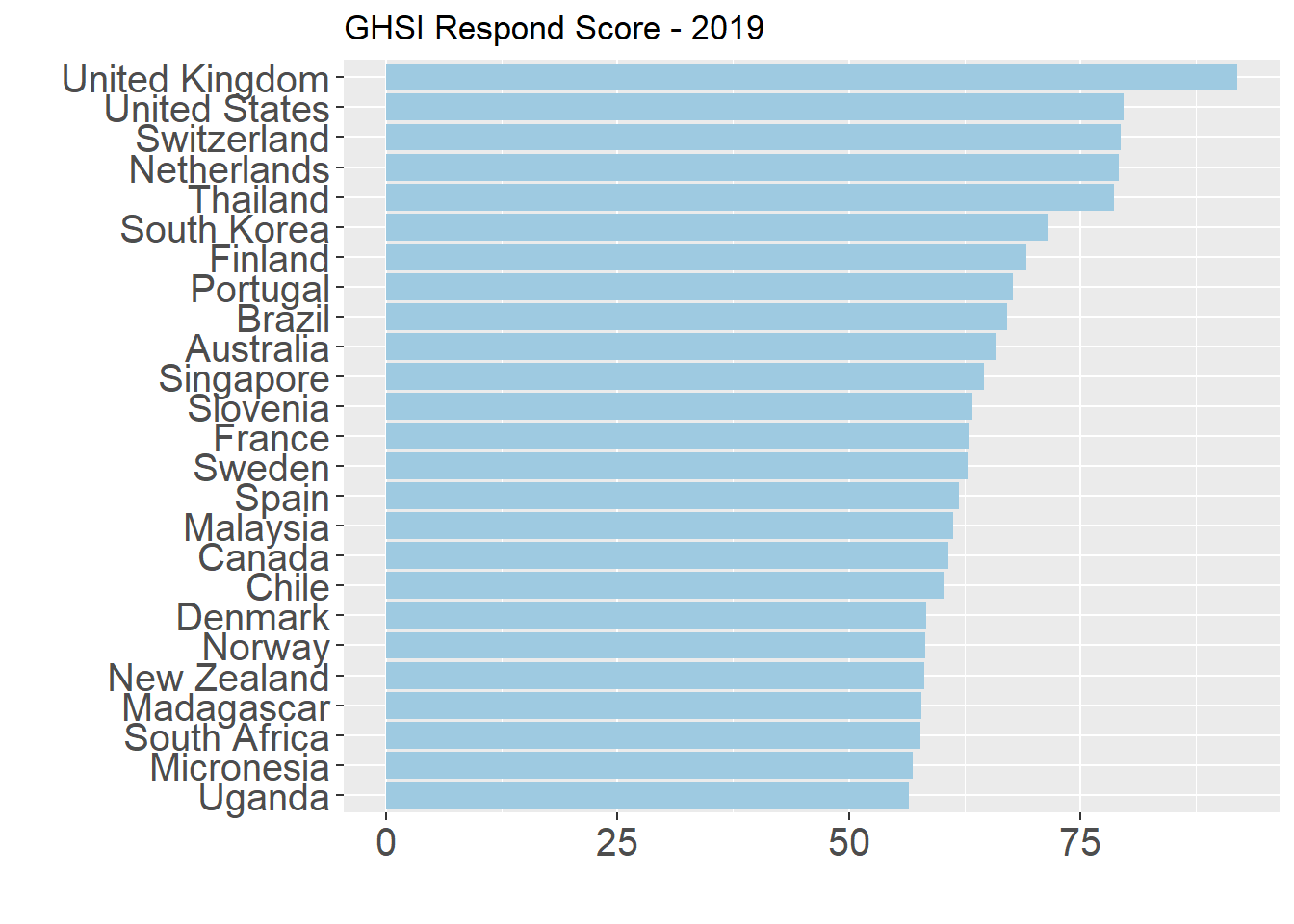

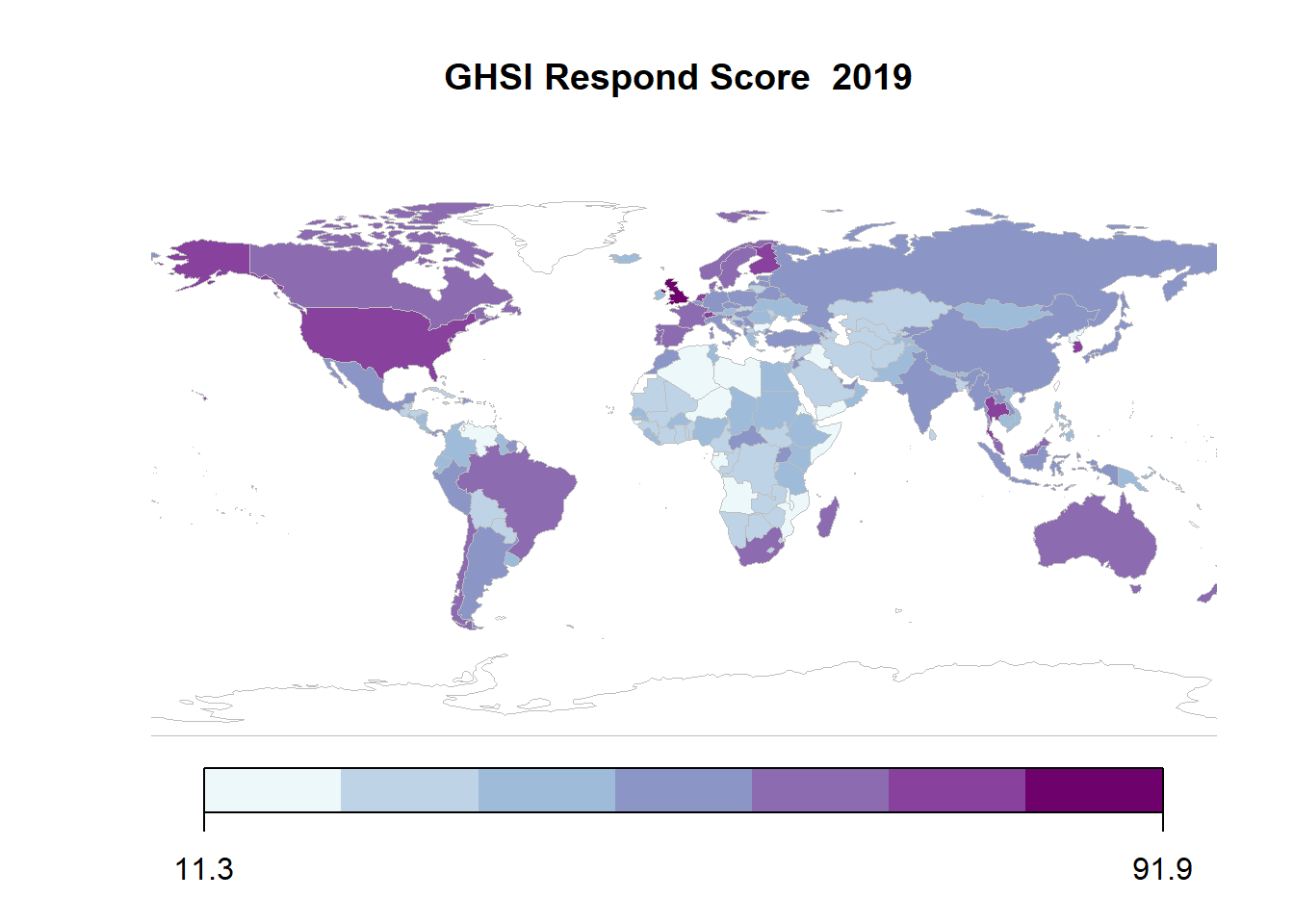

Factor 5: Respond

The Respond score is heavily based on the accessibility of plans to respond to pandemics and processes in place for when they occur. The principal indicators that comprise this category are emergency preparedness and response planning, exercising response plans, emergency response operations, linking public health and security authorities, risk communications, communications infrastructure access, and trade and travel restrictions.

The GHS Report 2019 notes that they find only the top nine countries below (5 percent of all assessed) to be in the well-prepared tier, which indicates the overall weakness of all countries on these factors. Many of the same countries at the top of the Detection category also appear here, and many of the middle-income countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Georgia, South Africa, and Thailand are at the top in both. However, in this case there is a significant gap between the first and second country: the United Kingdom score of 91.9 is more than 10 points better than the United States (79.7). According to the main report, the difference between these two specific countries lies in the Exercising Response plans, which focuses on whether countries have carried out biological-threat exercises with the World Health Organization and review of best practices following such an exercise in the past year.

Factor 6: Risk

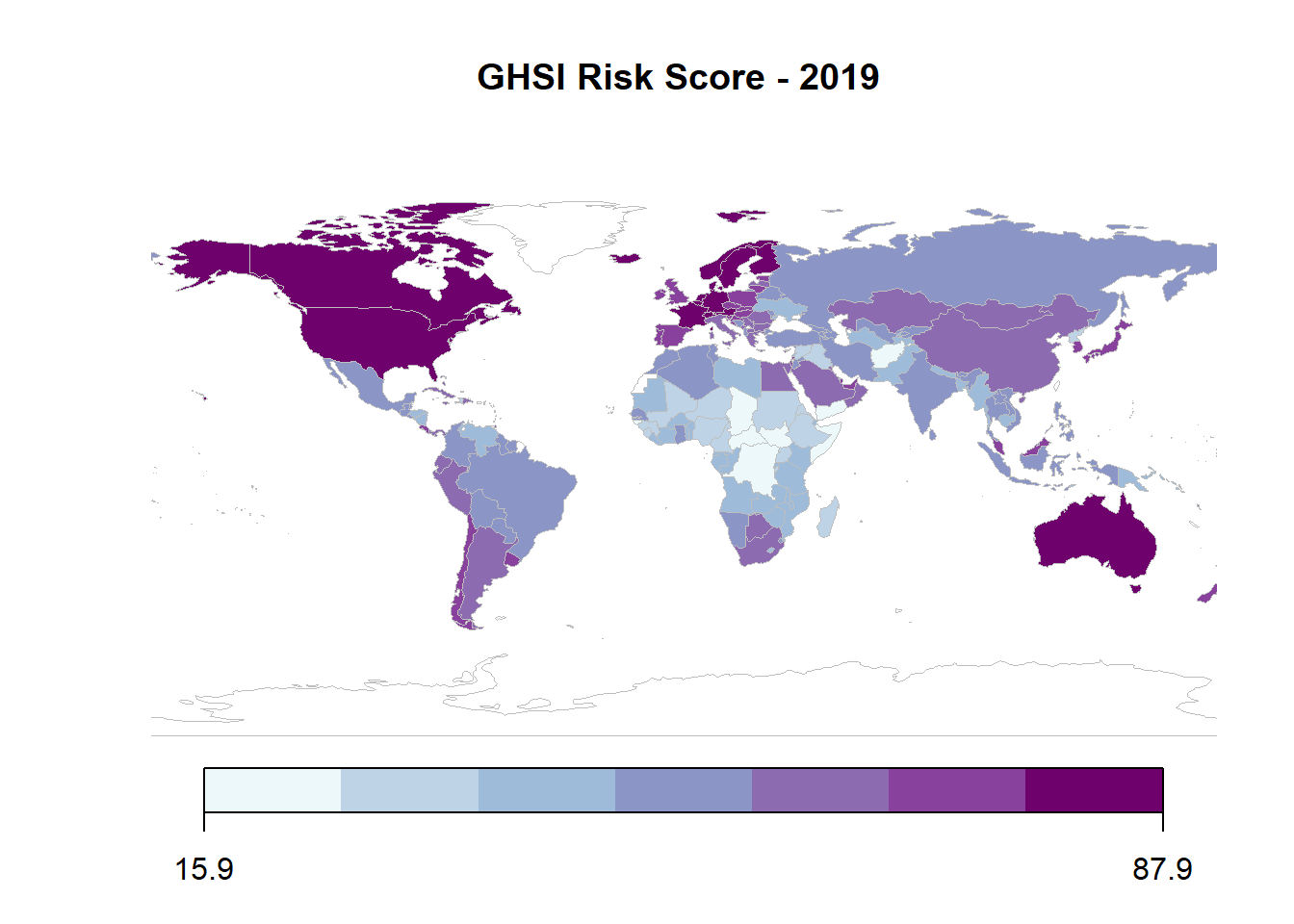

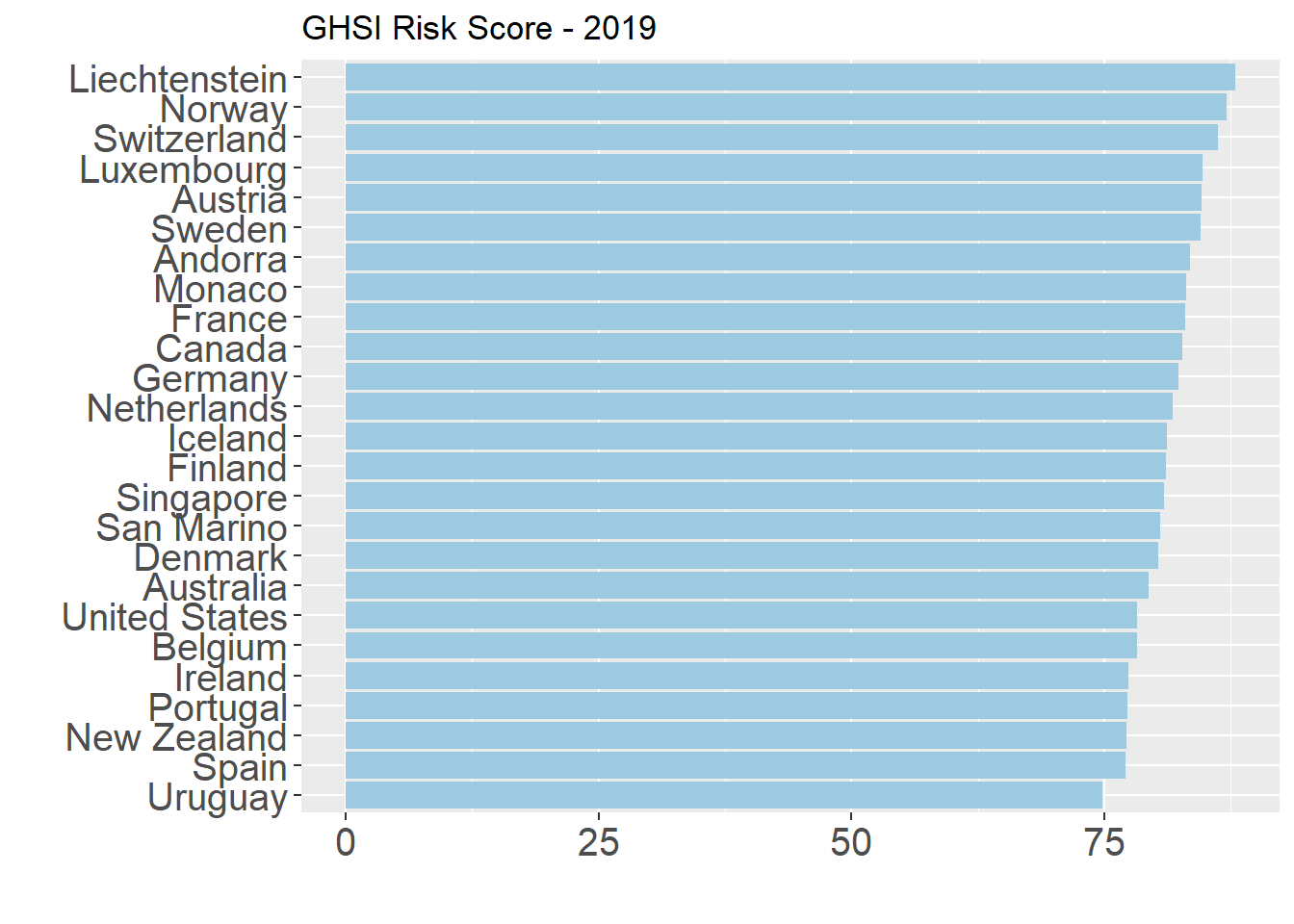

The final score of the GHS that we highlight is the overall Risk score, which considers political factors such as overall government effectiveness, socio-economic resilience and human capital factors, infrastructure capacity, environmental risks, and public health vulnerabilities. While many of these factors come from secondary sources (i.e. the Government Effectiveness score of the Economist Intelligence Unit and Gender Equality score of the United Nations Development Program), collectively they provide insight on the overall state capacity and ability of governments to move effectively in times of crisis. Unsurprisingly, many of the middle-income countries score worse on this model, given their issues with inequality, which reduces overall human capital levels. They also have relatively weaker scores on the Infrastructure and Environmental Protection indicators.

The Risk score overall favors smaller countries over larger ones. While the United States and United Kingdom both excel in all other categories of the GHS Index, the Political and Security Risk and Environmental Risk indicator scores drag them down overall.

These indicators provide some important information on the different health systems around the world. They also give us some signs on how countries will handle an outbreak such as COVID-19 in terms of detection, responding, and providing care as the number of cases increases. With the availability of data on testing, cases, and mortality rates, it’s an opportune moment to reflect on actual country responses and how informative these measures have been in predicting them.

In the next part of this series, we will examine how these measures compare to these responses using the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker developed by the Blavatnik School of Government of the University of Oxford.