Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

We’re Putting Citizens at the Center of the Design Process in Guatemala

Dec 19, 2016

Esta entrada también está disponible en español.

Update: Somos Chiantla is now available for download to Android devices. A follow-up post covers the launch event and next steps in development.

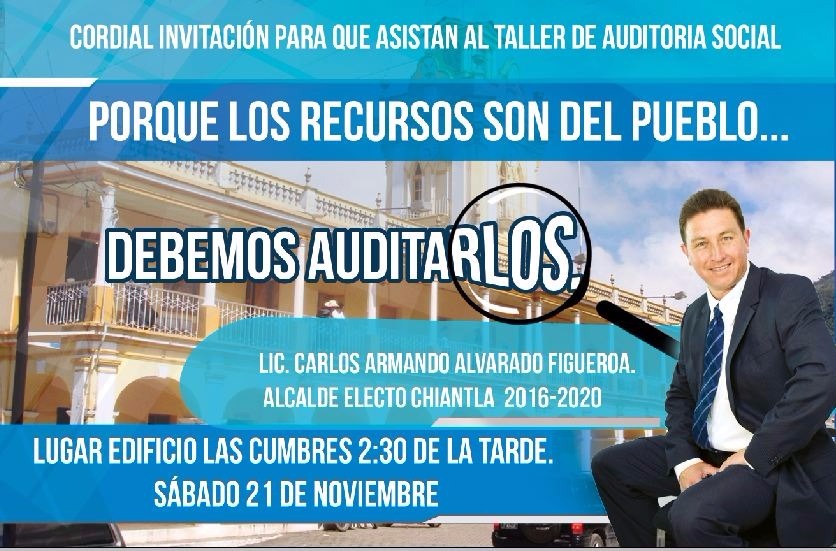

Back in late 2015, the Nexos Locales project in Guatemala received a novel inquiry. It was from Carlos Alvarado Figueroa, who had just been elected mayor of Chiantla (CHEE-ahn-tlah), a municipality of 75,000 in the Western Highlands, and he had an idea. Alvarado had been elected on a platform of budget transparency and social audit and was part of a wave of good governance reformers that swept into office on the heels of the Línea corruption scandal, which saw both President Otto Perez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti jailed. He wanted DAI’s help to design and develop a mobile tool to give the citizens of Chiantla (Chiantlecos) better access to municipal government. In particular, he wanted to give Chiantlecos an easy, transparent view on how his government was allocating and spending money, facilitating social audit and giving citizens the ability to more easily communicate with his administration. So, the project called me, and I called the Mayor.

Mayor Carlos Alvarado’s post-election Facebook banner image promoting social audit. Text reads: A cordial invitation to participate in a social audit workshop. The resources are the community’s, and we should audit them!

Citizen-Centered Design

After a few rounds of discussion and consultation with Mayor Alvarado and the Nexos Locales project team, we agreed to a design process placing citizen needs at the center of our decision-making. How? We chose to involve Chiantlecos in the design process from beginning to end, starting with face-to-face interviews on key design factors such as access to mobile technology, information flows via traditional and new media, and app choice. We also asked questions about the social media ecosystem, citizen opinion of government performance, attitudes about municipal government transparency, and which municipal services they would like to access.

If you’ve been following Digital@DAI, this approach might sound familiar. That’s because it’s very similar to our Digital Insights process. The primary difference is that the interviews were conducted by a partner, a local nongovernmental organization called ADESJU, whose enumerators we trained via the internet. While this approach meant less face-to-face time with prospective users, it was expedient given the budget and timeline constraints we faced.

.jpeg)

ADESJU conducts an interview with a Chiantleco in the municipality’s periphery.

ADESJU interviewed 100 citizens in the city center, periphery, and in the rural highlands. Half were men, half were women, and a participants ranged from 16 years old to 70. Thirty were part of the local municipal civil society advisory council. Below is a sample of what we found, followed by some discussion of how it impacted our design process.

Key Observations and Discussion

-

There were a lot of smartphones. While this is not a scientifically representative sample, we were surprised that 58 percent of those we interviewed had one. The smartphones skewed urban, likely due to cost and accessibility. Still, the presence of so many gave us confidence that there is a market for a tool accessible via smartphone. We chose to build an app over a mobile-first web page because we found that most of the people we interviewed used pre-paid mobile services, and pay a premium for mobile data. That being the case, we wanted to limit the amount of data that citizens needed to download each time they use the tool, and refreshing an entire web page is more data-intensive than simply refreshing a budget visualization. I’m aware that this decision will give way to new challenges–getting people to download the app in the first place, and ensuring they have enough space on their phones–but I’m confident that by working through our municipal and civil society partners, we can address these challenges.

-

Facebook and WhatsApp were hugely popular and accessed primarily via mobile. We’ll be looking for ways to take advantage of both. Currently one of the four key components of the app is a direct link to the municipality’s Facebook page, which the municipality updates with information, events, and photos multiple times a day. Given its popularity, we see this as a viable forum for creating more citizen engagement. Of course not everyone has access to Facebook, so in the future we’ll be looking for ways to engage that population through texts and live events.

-

When asked, the most requested functionality was budget transparency. This will be a core component of our final product, and we’ve been working closely to with Guatemala’s municipal budget and expenditure data system via the Ministry of Finance’s Office of Municipal Financial Assistance (DAAFIM for its name in Spanish) to roll it out. In my mind, it’s the single most important element of the system, although when we’re promoting it to citizens we’ll probably focus primarily on the problem reporting function, much like the municipality of Mixco did with their excellent new e-governance app.

-

We’re also building a simple problem reporting module, which will allow citizens to report potholes, electrical failures, issues with water provision, etc… quickly, and get that information to people who can solve the problem quickly. The challenge on the part of the municipality will be ensuring quick and consistent responses to reports submitted, or public confidence in both the app and in Mayor Alvarado’s administration will suffer.

Where to Next?

We’re moving forward with a design and development team in Guatemala City. I had originally hoped to find a team in Chiantla, Huehuetenango, or Quetzaltenango (where Nexos Locales is based), and while there are a few software developers in those areas of the Western Highlands, we found an excellent team with civic technology experience in Guatemala City and decided to go with them. They’re led by the very clever folks at Explico Analytics and Ludiverse. In terms of developing local capacity, Mayor Alvarado contracted a local computer science student as our primary contact, and we’ve been working with him to engage more Chiantlecos the design process. At the moment he’s running a contest to crowdsource a local name for the app (the working title is MiMuni), promoting the app and the contest in local schools, planning two rounds of user testing in February, and working with our partners in the municipality on a communications and outreach plan. Stay tuned!

Mayor Alvarado announces the app to the public at the lighting of Chiantla’s Christmas tree on December 8.

Thoughts or ideas on our work in Chiantla? Let me know on Facebook!, and Subscribe to our blog for more on DAI’s digital work around the globe.