Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

You Keep Using That Word: Why “Scale” Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means

Jun 13, 2019

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary offers seven definitions of “scale,” involving variously weight, fish, climbing, maps, music, and—unexpectedly—lumber. Notably, none of these meanings is a synonym for “to embiggen,” the usage favored in the tech and development worlds. In these environments, which share little else, taking something “to scale” always seems to evoke Carl Sagan-esque notions of quantity. What this reductionist approach to vocabulary loses (in addition to small stiff plates that cover much of the body of some animals) is the range that makes this word truly useful. In English, if not in Silicon Valley, you can scale up, but you can also scale down.

It is true that both in software and hardware, scaling up is often the challenging part, so perhaps it is natural that this is where the focus would lie. But one of the most interesting tech developments of the last 10 to 15 years has been the emergence of tools and approaches that enable the affordable fabrication of hardware in small quantities—say, less than 1,000. And at these small scales we find a wealth of opportunity.

It may seem like there is not much you can do with less than 1,000 units of a thing, but because hardware production has traditionally been the prisoner of economies of—yes—scale, this is precisely the level where many needs remain unmet. Particularly in developing countries, the ability to address problems with hardware without the infrastructure traditionally necessary to bring those economies of scale to bear has the potential to be a game changer.

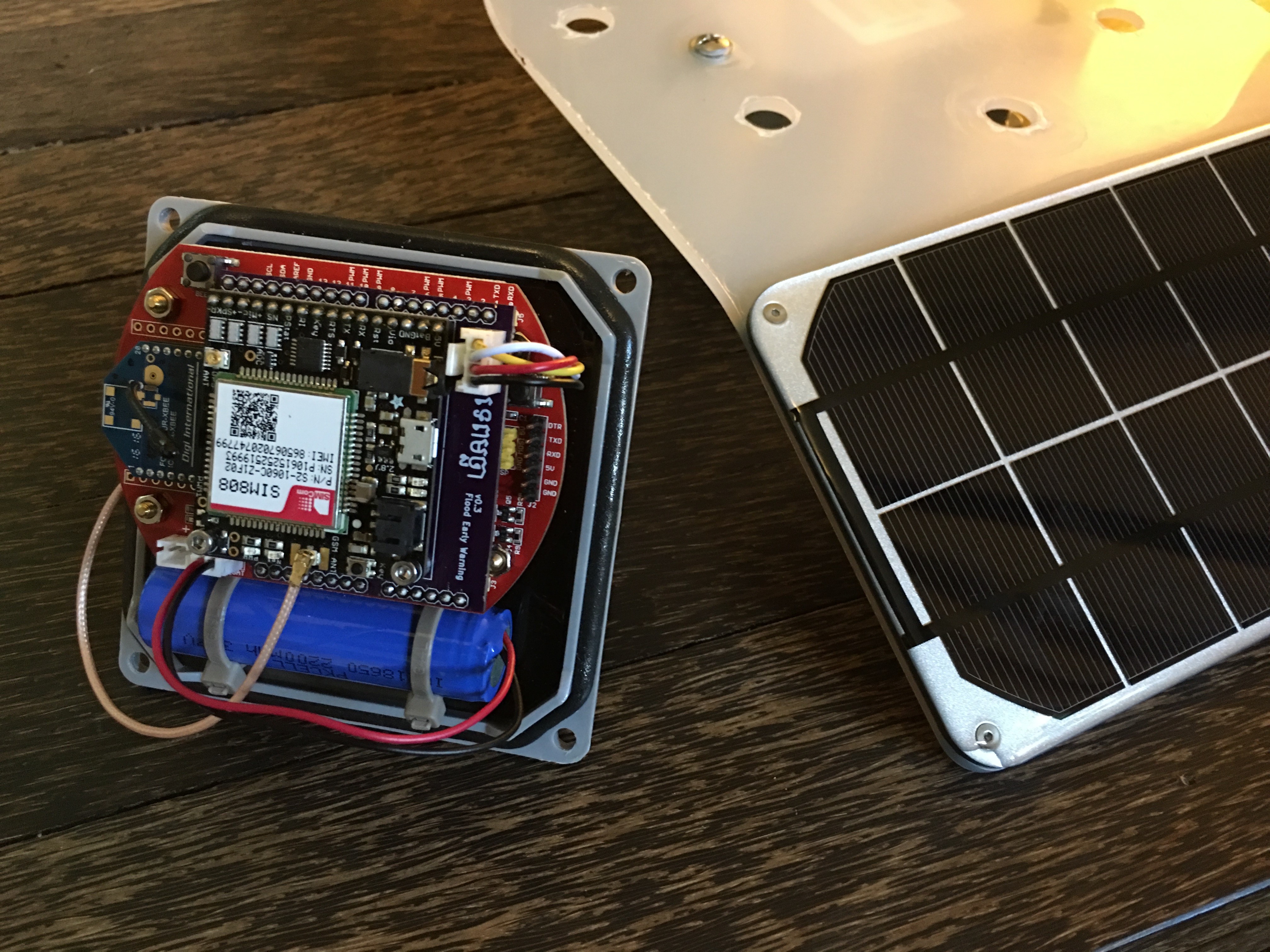

The Tepmachcha flood early warning hardware that we developed with the nongovernmental group People In Need Cambodia offers a vivid example. This device, usually mounted on a bridge, measures the level of a river or stream with sonar and uses cellular telephone networks to send its reading to a cloud-based server. If the river reaches a dangerous level, an interactive voice response (IVR) system is triggered, making an audio phone call to thousands of people downstream within a few minutes. By making voice calls rather than sending text messages, the system makes warnings available to citizens regardless of their literacy or the technological level of their phone (most phones don’t render the Khmer character set correctly). The world may not need more than 30 sonar stream gauges that play nicely with the RapidPro IVR software, but that is not a problem, because we can build 30 of them at about $300 each in parts cost, and they can be built and maintained by Cambodian technicians and their small companies.

The Tepmachcha flood early warning hardware.

With coverage that is nearly nationwide and about 75,000 current subscribers to the service, Tepmachcha shows that you do not need a large number of units to have a big impact. Similarly, in Indonesia we are working with local innovators to design a suite of open source hardware devices to provide water utilities with near real-time data on their distribution networks, allowing them to provide better, safer, more efficient water service. These, again, are devices which can be built locally—in this case by the utilities themselves—and a municipality such as Bogor, for example, with a population of nearly 1 million people, can be adequately covered with about 35 pressure and flow sensors.

It’s not just about electronics. In Cambodia, Golden West Humanitarian Foundation has an operation creating models of common ordnance for use in training professionals around the world in defusing unexploded mines and bombs. The traditional method for producing such training material is to disassemble real explosives that have been made safe, an expensive process that often results in a small, complex mechanism that remains hard to understand. Golden West uses 3D printing to create its models, allowing them to build them several times larger than life if necessary, with well-designed cutaways and dynamic mechanisms. I never truly understood the horror of a cluster bomb until I interacted with a 3D-printed model of one.

Landmine training model by Golden West.

Golden West funds the program through money it charges for the models, which at a few thousand dollars for a complete set is still a relative bargain. This is a highly specialized item—when I last visited Golden West in 2018, representatives estimated they had sold about 60 sets—that quantity could not be viably produced with traditional manufacturing methods.

So yes: In both technology and in development, scale is vitally important. Resources are limited and investments must be targeted at achieving maximum impact. But when looking for opportunities to make that impact, don’t limit your vocabulary.