Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Technology and Displacement: The Role of Digital Tools Among Displaced Persons

Feb 3, 2022

In a previous post from last March, I wrote about the reality of the gender digital divide, in which I noted the difference in digital access and usage among women and men globally and the lost potential that results from women’s lack of access. When able to access, understand, and leverage digital tools, women can use these tools to better their economic outcomes and those of their families and communities.

However, women are not the only group facing the reality of the digital divide. The United Nations Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation, a report presenting strategies for inclusive, equitable adoption of digital technologies, notes some of the many other groups affected by similar challenges, including “migrants, refugees, internally displaced persons, older persons, young people, children, persons with disabilities, rural populations, and indigenous peoples.”

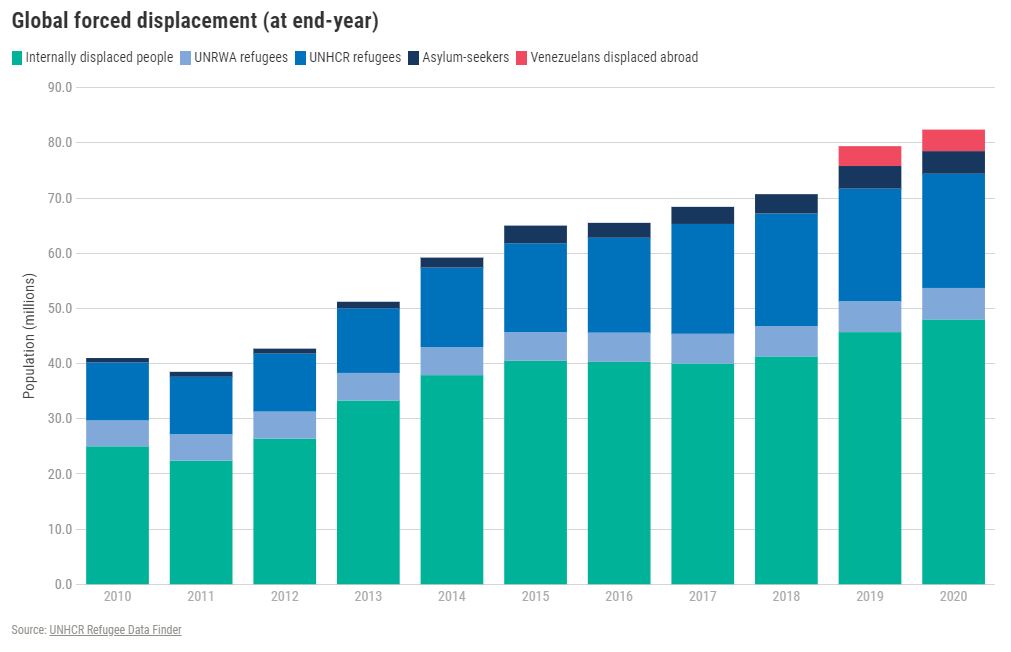

While there is much to be said about digital access among all of these groups, I was specifically interested in exploring digital usage among refugees and displaced people. How do these groups access and use digital tools? What are the most significant barriers they face in doing so? What kinds of special considerations need to be taken for these users? The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2020 Report estimates that 82.4 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide by 2020. With nearly 7.8 billion people in the world at the end of 2020, this number represented more than 1 percent of the world’s population.

The number of people forcibly displaced globally has continued to rise between 2012 and 2020. Source: UNHCR Refugee Data Finder.

How Do Displaced People Use Digital Tools?

Like other users, displaced people can use technology to access information, connect to resources, access funds, or communicate with others. In reading more about digital solutions to aid displaced people, I was reminded of many of the solutions that arose during the COVID-19 pandemic for the broader population. Refugees and displaced people, like many in the pandemic, value from being able to stay in touch with far-away families, receive remote health services, utilize forms of digital identification to access resources, or continue education or employment in which showing up to a physical location is no longer an option. DAI’s Center for Digital Acceleration recent work explored how to better leverage digital tools for children’s education in conflict-afflicted communities.

Barriers and Challenges

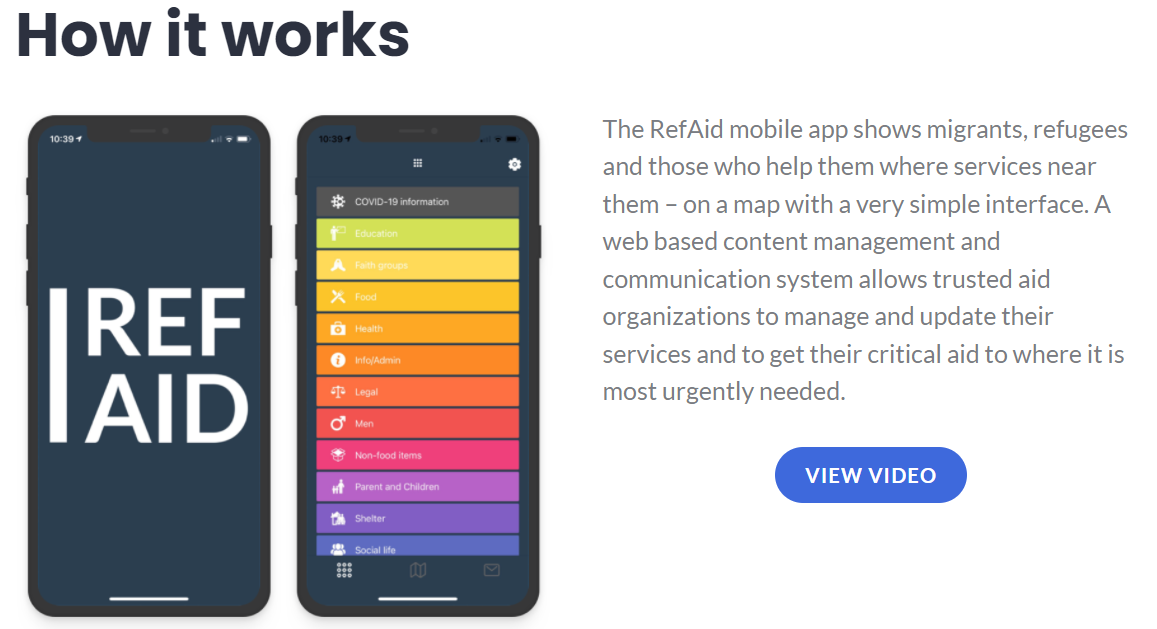

Refugees and internally displaced people face additional obstacles specific to their situations that may be assisted or exacerbated by technology. Online services and applications, such as Refunite, RefAid, The Welcome Card, and Ankommen, among others, can help refugees overcome language barriers, manage unfamiliar legal processes, and navigate everyday needs in their new location. However, using these tools and more basic services like checking email or sending WhatsApp messages relies upon the components of access that are often out of reach, such as reliable wifi, affordable data plans, electricity, and devices to connect. According to UNHCR’s refugee statistics, developing countries host 85 percent of the world’s refugee population, with the Least Developed Countries hosting 27 percent, exacerbating access gaps that already exist in many of these places.

A screenshot of the RefAid mobile application on the app's website. RefAid is available in multiple languages and provides resources across a variety of topics.

When digitally connected, displaced people may be particularly vulnerable to scams, misinformation, or disinformation that targets their particular situations. Late last year, an article from The New York Times described how false opportunities spread on social media lured migrants Belarussian-Polish border with the false promise of entry into the European Union only to endure long days in harsh conditions with no forward progress. The reality of “digital litter” also feeds into this problem. Digital litter includes applications, links, or other online resources that have not been kept up and are no longer relevant. Though well-intentioned in its initial creation, these outdated resources add to the confusion and misinformation that displaced people face and have the potential to lead individuals into wasted or potentially dangerous actions if the information is no longer valid.

The Importance of Inclusion

These realities only touch the surface of the numerous and varied challenges that forcibly displaced people face when navigating their journeys from initial displacement to resettlement. The efficacy of digital tools to improve lives and create opportunities for displaced people has been proven, but as outlined in the UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation, it is vital to recognize the difference between technological advancement and inclusive technological advancement. Leaving specific populations marginalized from digital tool access exacerbates existing inequalities, not only disadvantaging individuals in these groups at present but harming communities at large as the divide between those with access and those without widens. As we in the development community think about digital solutions, we must keep this reality in mind to best address the unique needs and vulnerabilities that displaced persons, and other disadvantaged groups face when seeking to better their situations through digital tools. For more information, check out UNHCR’s Connectivity for Refugees initiative, detailing the agency’s approach to ensuring displaced persons are digitally connected to better their futures.