Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Racist Hardware and What to Do About It

Jan 14, 2021

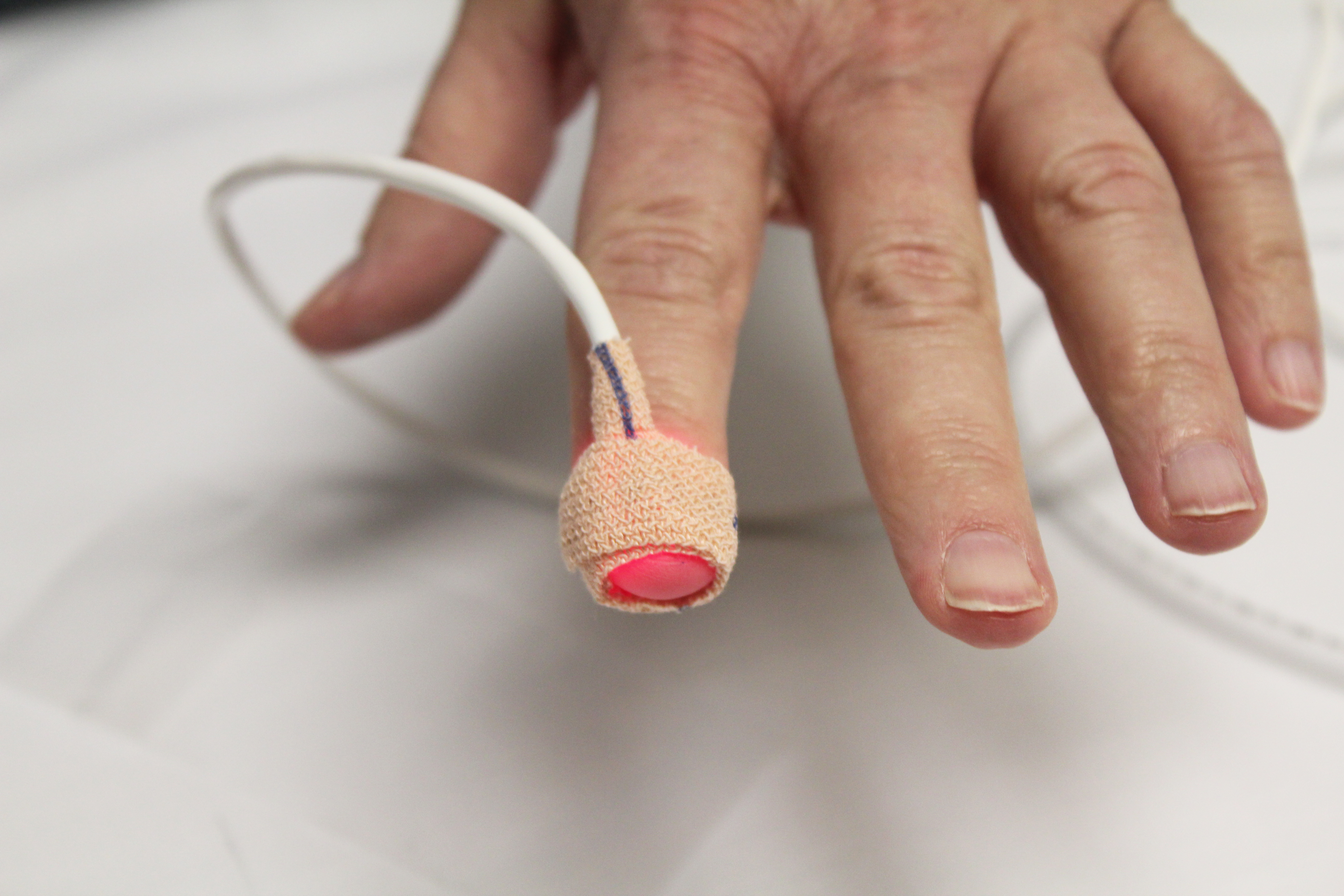

In an astonishing letter to the editor published in the December 17, 2020, edition of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), a group of five doctors from the University of Michigan Medical School presented findings from their study on adult inpatients receiving supplemental oxygen at the University’s hospital. They found that the variance between blood oxygen levels measured through a pulse oximeter—an optical device that estimates blood oxygen by analyzing the light absorbed in an extremity, usually a finger—and more rigorous (and invasive) analyses of arterial blood gas differed substantially depending on whether the patient was Black or white. Moreover, Black patients tended to get more optimistic readings from the oximeter. Such inaccuracies could quite possibly lead to worse clinical outcomes and could be particularly detrimental when treating COVID-19 as careful monitoring of patients’ blood oxygen levels can trigger lifesaving medical care.

Against the backdrop of the ongoing global conversation about racism and bias, one might ask whether the pulse oximeters in this study are racist. Can a piece of hardware even be racist?

Can Hardware Really Be Racist?

The word “racist” is a highly charged one in the United States, partially because people with different viewpoints have different definitions. For some, the word implies harmful intent more than harmful outcome. Many people holding this view would likely find the idea of racist hardware ridiculous. How can a printed circuit board be racist?

Like any other item of material culture, hardware cannot be untangled from the society that produces and uses it. While precise circuit traces and excitingly chunky injection-molded enclosures lend a sense of objective fact to devices for many users, and engineering and product standards actively seek to reassure the public, hardware is subject to the same assumptions and blind spots as any other cultural artifact. Racial biases in technology abound and are attracting increased scrutiny. Devices have been demonstrated to overtly disadvantage people of darker skin tones before—automatic soap dispensers and hand dryers are frequent offenders—but the consequences are generally brushed off as a nuisance from a piece of equipment that nobody places much faith in anyway. Not so with medical equipment.

The apparent existence of clinical hardware that gives misleading diagnostic information about Black patients significantly more often than white ones—leading to potentially widespread fatal consequences in today’s overrun intensive care units—should put to rest the question of whether hardware can be racist by any reasonable definition of the word. It can.

The Regulatory Layer

Most of us in the West assume that the government exercises a level of control over medical devices that would prevent problems like those described in the NEJM letter. Can a device with such a flaw really make it to market?

In the United States, pulse oximeters are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a Class 2 medical device. While manufacturers must apply for clearance on their design before marketing the device, it may surprise many readers that only Class 3 medical devices are evaluated for safety and effectiveness. Class 2 devices need only be “substantially equivalent” to another Class 2 device currently on the market.

The FDA provides specific guidance to its reviewers on how to evaluate applications for the clearance of pulse oximeters. The guidance is silent on specifically evaluating any variances in performance by race, ethnicity, or indeed other seemingly relevant criteria such as age or body composition, though it states that if individual test subjects’ results show “noticeable outliers,” the applicant should include “a discussion of the state of health, subject characteristics, test setup, test procedure, and any other factors that may have affected these data points” and explain why any outliers “do not raise safety and performance concerns.” Looking at the Michigan researchers’ data, it is not obvious that any individual would be seen as a “noticeable outlier,” though the skew for the groups, when disaggregated by race, is pretty clear.

The FDA recommendations call on manufacturers to conduct testing as described by international standards, specifically suggesting International Standards Organization (ISO) 80601-2-61. This 90-page standard requires manufacturers to disclose the skin color of individual trial participants—thus recognizing that skin color in particular could affect readings of an optical device—but not to actually present aggregate results by skin color, which would highlight any variances. Skin color, of course, does not always indicate one’s race and is only one of the possible causes of the bias documented in the NEJM letter. The Michigan researchers tried to correct for other medical conditions, such as diabetes, that disproportionately affect marginalized racial groups, but a variety of other etiologies related to socioeconomic or other factors could be at work.

The Michigan findings were published as a letter to the editor in NEJM and are not yet peer-reviewed. But whatever the cause of the study’s results, or if it is later found that there is more to the story, it is striking that there is nothing in either the ISO standard or FDA regulation that would identify or prevent marketing or use of a pulse oximeter that works to the detriment of Black patients in precisely the way the study results describe.

What to Do About It

I presume no ill will on the part of the engineers and clinicians who designed and tested the Michigan pulse oximeters, nor on the regulators that cleared it, nor on the subject matter experts who wrote the standards. On the contrary, I imagine that all of these people wanted to promote fair and positive outcomes. But if hardware is material culture, then it must reckon with the insidious problems that have deep and wide roots in the handful of cultures that produce most of it. There are some lessons we can learn from the pulse oximeter case that can help us make more equitable hardware:

Diversity in design

We are all products of our own experience and bring with us assumptions and blind spots that come with that experience. This is why it is so important that designers, regulators, engineers, and others involved in developing and producing hardware come from a variety of backgrounds to cover one another’s blind spots and ultimately produce a better-quality outcome.

Diverse representation must not come from just one society, but from around the globe. A core principle of DAI’s Maker Lab is the idea that hardware designed and built by people in a narrow socioeconomic band of a handful of developed countries often does not serve users in developing countries well. The Lab works with innovators and users in the countries where we work to ensure that they can design, produce, and maintain hardware that works for their specific needs. As the technology used to design and implement hardware solutions gets more accessible, we need to actively put it into more—and different—hands to get better results for all.

Human-centered design

Following the principles of human-centered design in a thoughtful and rigorous way, being sure to include a diversity of intended users, can reduce many of these issues. This may not seem like a revelation, but it is surprising how often this is not done. Thoughtful consideration of how different groups of users might interact with a solution in the aggregate should lead to careful data collection and analysis of the implications of those differences.

Open standards, data, and transparency

Having more eyes on standards—particularly eyes that do not belong solely to industry—is the easiest way to get better standards that serve a wider range of users. Anyone can access ISO’s standard on pulse oximeters… provided they are prepared to pay $230 to look at them. Not only does this squeeze out potential reviewers, but it does so with particular prejudice toward those at the bottom of the pyramid.

Summaries for FDA device applications are easy to find; the backup documentation is not. Having publicly available information on test data, in standard formats that simplifies analysis, would help purchasers, civil society, and the public evaluate these kinds of issues and provide additional incentives for manufacturers to get it right.

Evaluating hardware designs only against the performance of previously approved ones risks perpetuating poor design choices. Designs should be assessed on their own merits, against transparent criteria.