Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Government-Run Digital Tools to Combat Corruption: Can They Work?

Sep 21, 2023

(Originally published on DAI’s Developments blog.)

In 2014 and early 2015, more than 3,000 volunteers peered into their monitors to try and decipher poorly handwritten and scanned annual asset declarations from Ukrainian officials that described their properties, vehicles, land, commercial venues, bank accounts, and cash. It was a tedious task. At times, it seemed that civil servants deliberately used bad handwriting to comply with the requirements of paper-based transparency. By 2022, before the full-scale war, any internet user would have free access to more than 2.5 million asset declarations searchable through the public registry of the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption of Ukraine and at least one advanced civil society powered instrument that worked on the data-fuel from this registry. The difference was night and day. Now, instead of peering into illegible scans of handwritten scribbles, with a click of a button you can check whether a company owned by civil servant John Doe won any government contracts last year, and whether his elderly parents bought a mansion close to the capital or a new luxury car—and ask questions to the authorities.

Governments worldwide are rushing to use digital technology to reduce corruption. Over the past decade, state agencies have increasingly used digital systems to conduct anti-corruption investigations, gather and analyze asset declarations, automate electronic procurement processes, and analyze open data. Despite initial implementation difficulties in many countries, these digital tools have proven effective. Many governments that benefit from donor assistance are now asking to prioritize resources for upgrading or building new IT systems to help counter corruption.

In this article, we reflect on some lessons learned in supporting such government-commissioned digital systems, as one approach to assist with dekleptification efforts.

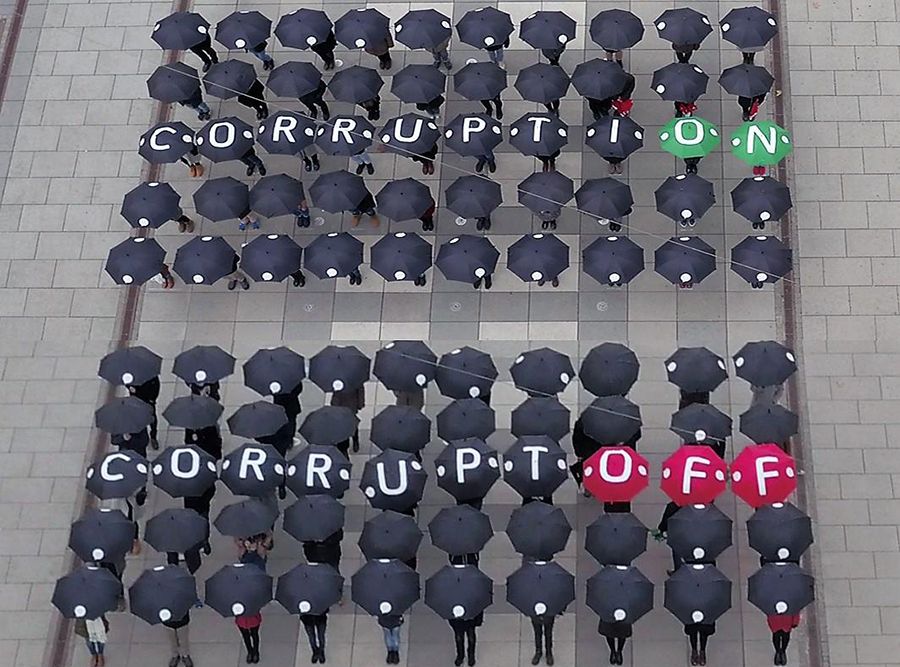

Photo: FOL/USAID Kosovo.

Lessons Learned from Government Tech Solutions

Knowing the digital ecosystem of a country and understanding the relevant political system can save donor resources and increase the probability of success. When a window of opportunity opens to make meaningful progress on anti-corruption reform in any country, international partners often race forward with ideas, concepts, or early-stage prototypes of anti-corruption digital tools for government counterparts. While a rapid response and agility are essential to capture the momentum, the “thinking and working politically” mindset should guide decisions about supporting government-run anti-corruption digital solutions. A nuanced understanding of the spectrum of digital transformation issues in a country is key to estimating the true financial, human, and political cost of digital anti-corruption tools. Development partners will need to consider (i) the level of maturity of the digital government (ii) the regulations governing information security in government systems, (iii) the availability of linked registries and databases between different government entities, (iv) and the state of the market for design and deployment of similar digital systems. This detailed vision will allow development partners to anticipate possible bottlenecks and pitfalls.

A digital political economy analysis is better performed by a team of specialists in broader governance issues and digital transformation, as opposed to only governance experts or exclusively IT specialists or engineers. A solid foundation for such a targeted analysis could be a Digital Ecosystem Country Assessment (DECA), or a similar broad review of the country’s digital transformation.

Yet it would not be enough to concentrate exclusively on the “digital” aspects. Government-owned anti-corruption digital solutions may be seen as a threat to the status quo of some government stakeholders or political elite. For instance, a truly transparent electronic declarations system for public officials, with robust mechanisms for data verification, will not be welcomed by those who will now have to show their wealth but lack the means to justify it. Political party leaders who are accustomed to hiding their sources of income or spending will not welcome a strong system for reporting party funding, particularly one that allows open data for public scrutiny. Similarly, businesses that have previously relied on nepotism or conflict of interest to obtain state orders will not be pleased with a reliable electronic procurement system that includes a complaint review process. Development partners should prepare for potential obstacles, such as legislative pushback or deliberate attempts to provoke issues (e.g., using a fake electronic identity to suggest system compromise). There may even be instances of indirect extortion, such as last-minute requests for additional equipment made under duress.

A proper, in-depth, digital political economy analysis, based on in-depth interviews with diverse stakeholders, will help identify risks: from lip service given by officials (where in fact, there is no intent or interest in a well-functioning system) to potential areas that may be sabotaged by mid-level executives. Proper risk identification and understanding of a technical and political landscape could help partners consider risks, mitigate potential adverse consequences, engage in robust contingency planning, and estimate the long-term costs of proposed interventions.

Photo: USAID Malaysia.

Anti-corruption digital solutions should be open, transparent, easily accessible, and understandable. While government-owned digital tools are often positioned as “systems that operate best in secrecy” (invoking the notion of “security through obscurity”), an opposite approach is possible and, in the case of anti-corruption digital instruments, far more desirable. However, barriers can emerge even if a government counterpart is persuaded that the system ought to be open for public scrutiny—as is the ProZorro eProcurement system in Ukraine, whose software code is open access.

To achieve transparency and accountability, the source code or at least a logical model of the digital solution and its algorithms (both AI-powered and rules-based, simpler algorithms) should be open for review and explainable. If an electronic asset declaration system flags a file for additional scrutiny, the public should be able to know what criteria are used, and how such alerts are triggered. However, many algorithms and the underlying source codes are supplied by private sector stakeholders and are protected by intellectual property rights. Unless anticipated in agreements between the donor, government, and vendor, this impedes their openness and explainability. AI and machine learning techniques further complicate transparency. In such a case, providing the algorithm’s source code may not even be sufficient as an explanation of how the results of an algorithm were produced is required. Governments around the world are increasingly introducing algorithmic transparency standards. For example, the United Kingdom was one of the first governments to embed such a standard into its National Data Strategy. Chile is also working on algorithmic transparency standards in public service delivery.

It’s important for international development partners to be aware that even anti-corruption digital solutions can be susceptible to corruption. There is a risk of potential misappropriation of funds, whether they are public or provided as international technical assistance. Improper use of the technology itself is also a concern. The design, development, certification, installation, and operation of anti-corruption digital solutions may involve corruption risks. Because they administer public funds, local authorities are typically bound by domestic fiscal controls and potential criminal sanctions, but this is not usually the case with foreign assistance. Domestic laws rarely penalize misuse or abuse of donor funds.

Various issues may arise, from unnecessary procurement of expensive IT equipment to unexplained “maintenance works on the source code” that may be fictitious or rendered at inflated prices. Often, pricing of the software development or maintenance can become problematic, and “human hours” spent on “bug-fixing” can be hard to verify. Double billing (for the equipment already paid for through the state budget) and nepotistic selection of vendors are other ways that an anti-corruption digital solution may end up mired in unethical practices.

Would it be possible to start from scratch and have an open, transparent selection of a vendor with fair prices through an open competition? This ideal could be achieved with political will from the very top of the country’s leadership chain, but even in these cases, the reality of government-owned and operated systems can be troublesome. Often, national authorities undertaking digital initiatives must deal with legacy software and hardware. Almost universally, documentation for previously developed digital systems will be obsolete, incomplete, or missing altogether, making the transition to new digital systems or linking the old (existing) and new (intended) digital tool harder.

Moreover, if there are legacy solutions that need upgrading or linking to (for data transfer and interoperability), the issue of a “vendor lock-in” may emerge. You’ve all migrated from SharePoint to Google Drive, right? Remember the re-adjustment and learning curve? Now, let us imagine how much it would actually cost to “transition” from one sizable state data registry to a different platform. Vendor lock-in is a situation where a client is for various reasons forced to rely on only one supplier (a private or state-owned enterprise or an IT company) or a certain proprietary technology. The given company, in the absence of proper documentation for the IT system architecture, becomes the only “institutional memory” available to enable the progress of the project. This dependency has previously caused situations when the vendors abuse their unique position and request additional funds (from the donor or the state budget) to introduce changes in a digital system.

Finally, even well-designed digital anti-corruption tools are not immune to human error or malicious intent. Cases could range from misusing anti-corruption systems to extort civil servants or deliberately “closed eyes” to cases that should merit investigation, to introducing false data, or using insider knowledge and access to such instruments to tip off suspects of ongoing investigations or impending searches.

Photo: USAID Haiti.

Building prototypes with civil society organizations (CSOs) is valuable but the resulting tools require significant resources to mature into government-owned systems. Over the past decade, hackathons, codefests, and tech-sprint events have become popular with international development partners. Such events increasingly source prototypes of digital solutions from the civic tech sector, including coalitions of CSOs, investigative journalists, and businesses. Supporting digital solutions developed by the nongovernment sector is faster and easier. Any digital system should comply with the national standards and regulations (for instance, personal data protection and cybersecurity) but standards and enforcement are usually tougher for government-run anti-corruption investigations or monitoring tools. By supporting civic-based digital initiatives (nested with CSOs or journalist consortia), donors are not only developing the capacity of the nongovernmental actors, but also taking fewer risks: a nongovernmental instrument can be very flexible, and liability is unlikely if it fails, gets hacked, or inadvertently leaks data.

In many cases, after the so-called MVP (minimum viable product) is incubated, donors usually plan to promptly transfer the tool to the state counterpart, which rarely works as intended. Startup-grade solutions usually lack required technical documentation (hence the risk of vendor lock-in) and are not known for undergoing rigorous testing (including for information security vulnerabilities). Cases exist where donor-supported solutions incubated by CSOs have had to be significantly remodeled due to technical or documentation-related issues.

Government-based, owned, and operated digital solutions, especially the ones that suggest there may be fraud or other corruption-related issues, ought to rise to a very high level of credibility in the eyes of the public as the cases go to investigation, prosecution, and adjudication. It is one thing if a civic-based or journalist-driven platform alleges that a Member of Parliament has certain breaches of integrity, and the Member then threatens a slander lawsuit. It is much more serious if allegations are made in court by government prosecutors based on data from a government-owned, operated, and certified digital system. If the public does not perceive these systems as secure and trustworthy, the consequences of ending high-level impunity may be much more dire.

Despite these difficulties, it is worthwhile to engage in software innovation projects bringing together civil society, business, and government. Such collaborations are not primarily about the quality of the software or the IT system as a whole. They are more about spurring innovation, agreeing on the public narrative around corruption, setting expectations for the adoption of transparency tools by the government, and encouraging collaboration between the stakeholders. At the same time, if partners decide to invest in a CSO-based solution for transfer to a state entity, they should not expect it to be immediately operational. Additional funds will be necessary to make sure that the startup-grade system matures into a potent, government-based anti-corruption instrument.

Avoid the Pitfalls

Digital anti-corruption solutions—whether government- or nongovernment-based, whether on blockchain or using AI—are likely to proliferate as the world becomes more digital. The volume of digital data is projected to almost double by 2025. Governments are nudged to digitally transform aspects of their operations, and that includes ethics, integrity, civil service hiring practices, anti-corruption and transparency measures, public procurement, and functions of the oversight institutions—to name a few. As we learn more about applying government-run digital solutions for anti-corruption efforts, it is incumbent on the international development community to avoid the pitfalls that have already been discovered in practical implementation worldwide.