Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Frontier Insights Yemen: Understanding Children’s Digital Access

Oct 7, 2021

Throughout this past summer, DAI’s Center for Digital Acceleration has been working with Sesame Workshop to explore the possibilities for using digital tools to provide education services to young children living in crisis-affected communities.

Using DAI’s Frontier Insights™ methodology, our researchers in Colombia, Yemen, and South Sudan talked to children and their parents and caregivers to understand communities’ barriers to connectivity and their technology habits. Through this research, we sought to understand how technology might be leveraged to improve access to educational video content. In this series, we share our findings and interesting insights into the digital lives of children in these contexts.

In August, our research team traveled to two internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in rural Yemen and interviewed 50 people, including children, ages 3–8, and their parents or caregivers in the Randa Shaya and the Arrahma camps located in Ibb, three hours outside the capital Sana’a.

Key Findings

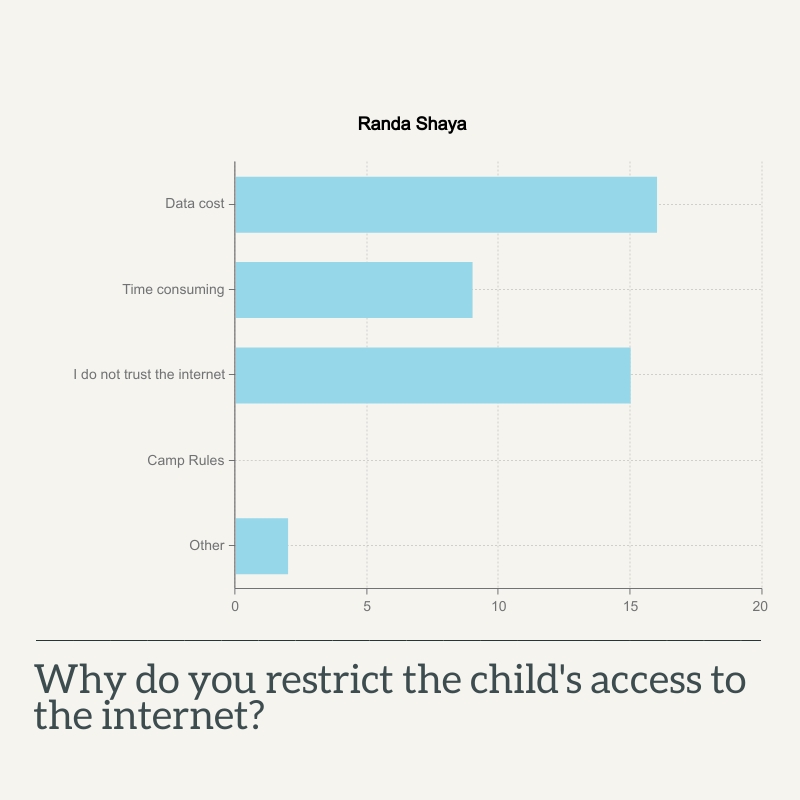

In both Arrahma and Randa Shaya, the main barrier facing IDPs is poor electricity and connectivity infrastructure, particularly as the “workarounds” such as paying to charge, using mobile data, and using internet cafes, are all too expensive. Interviewees in both locations raised concerns around the negative influence of the internet on children, particularly worried about children’s access to sexual and violent content.

The way in which children watch videos differs greatly between the two locations. In Arrahma, children watch television on a daily basis, with programming selected and supervised by the caregivers of each shelter. In Randa Shaya, however, some children do use mobile phones and do so regularly, watching videos that have been uploaded from a USB.

In this article, we further detail the findings of the research. As the findings in each context were very different, we will split this piece by location.

ARRAHMA

Arrahma camp consists mostly of large households, or shelters, of 10 to 12 orphaned children, supervised by a female caregiver. These children have lost their parents due to the war and come to the camp from different places in Yemen, including Taiz. Around 130 children live in the camp with their caregivers.

1. Most caregivers have a mobile phone but do not access the internet on their mobile phone

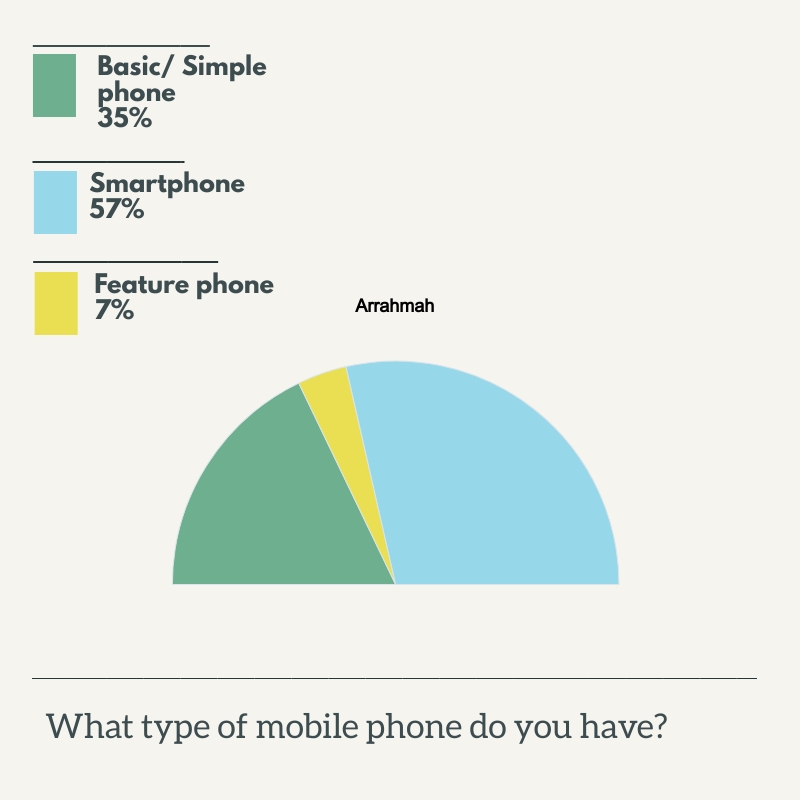

All interviewees own a mobile phone, reporting that they use it mostly for phone calls and messaging. Six women report watching videos on their phone and only five use social media. The adult interviewees who watch videos purchase them for around 1,000 Yemeni rial (videos up to 8GB) at the internet café and download them onto a USB. They then use a connector to plug the USB into their phones so that they can save them on their phones’ SD cards.

Only 28 percent of the female caregivers interviewed access the internet on their phones, despite most having a smartphone or feature phone. They report that the internet connection is poor and data costs too expensive. Those who do use the internet tend to use the expensive mobile data, as the community access point for caregivers offers only a poor wifi connection.

2. Most children do not use a mobile phone, as caregivers fear inappropriate content, but all children watch TV

Only four children in the Arrahmah camp use their caregivers’ mobile phones occasionally to make calls. There are strict camp rules around the internet and content access for children: camp management dictates what videos caregivers can provide to children, due to fears over inappropriate content such as sexual content or content that is not “Islamic.” Half of the children report that they want to watch cartoons or fighting videos but are not allowed.

Each of the shelters has a television, which caregivers allow children to watch before and after school. Camp management download videos at the internet café and give the caregivers USBs with educational videos, cartoons, and Quran-related programming that they plug into televisions to play. Children are always supervised.

3. All children have access to classroom-based learning

There is a school within the Arrahma camp and, of those interviewed, only two children are not enrolled in school—both male, due to recent arrival and trauma recovery. Caregivers report challenges mostly related to running the school, such as the expense of transporting teachers from their homes and insufficient equipment: There is often no electricity, no internet, no library, no games, nor video hall. There is a computer lab that was donated, but they are not able to use the lab because there is no power.

RANDA SHAYA

Randa Shaya is home to IDPs from different governorates, including Hodidah, Taiz, and Saada. IDPs from the most marginalized groups (known as the “Muhamsheen”) also live in the camp. The camp living areas are segregated due to tensions between the different groups. The camp contains 69 households and 150 children.

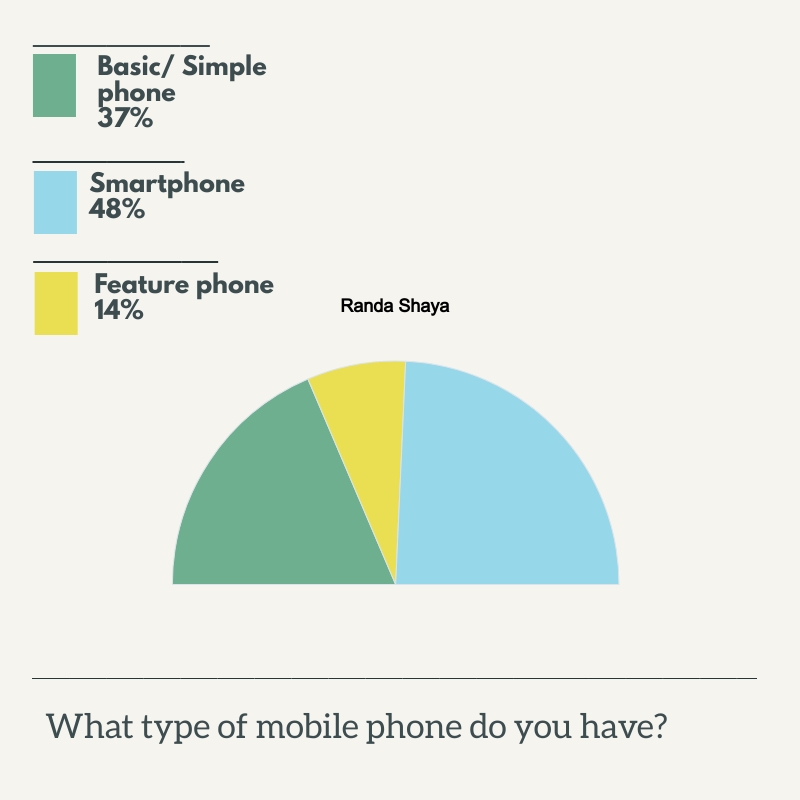

1. Most interviewees have access to a mobile phone and use it mostly for phone calls and messaging

All but one interviewee reports owning a mobile phone, however, many women commented that the mobile phones belong to the men in their households. All use their mobiles mostly for calls and messages, with half watching videos and a quarter using social media.

2. Electricity and poor connectivity affect how families use their mobile phones

All interviewees in Randa Shaya have electricity in their homes but note that it regularly cuts out. Forty-four percent are not able to charge their mobile phone at home, so they go to the grocery store. Since it costs 100 YR ($0.40) to charge a mobile phone, many limit their use of the device based on how much power is available, to avoid charging their phones too often.

In Randa Shaya, 63 percent of interviewees access the internet on their mobile phones but say that mobile data is very expensive. The high cost and lack of reliable power and quality internet access mean they are more reliant on the internet café to download videos for offline use.

3. Most people in Randa Shaya watch videos downloaded on their phones or on YouTube or Facebook

Just under half of the adult interviewees use their phones to watch videos. All of those who report watching videos do so by downloading files to their phones through USB, which they load at the internet café. More men seem to go to the internet café, and often sons or husbands will download videos for the family. A total of 16 adults report using YouTube and/or Facebook to watch videos and some mention that friends and family send videos on WhatsApp. Many note that the way they can access videos is limited due to cost and poor signal and therefore they rely on downloaded videos rather than online streaming.

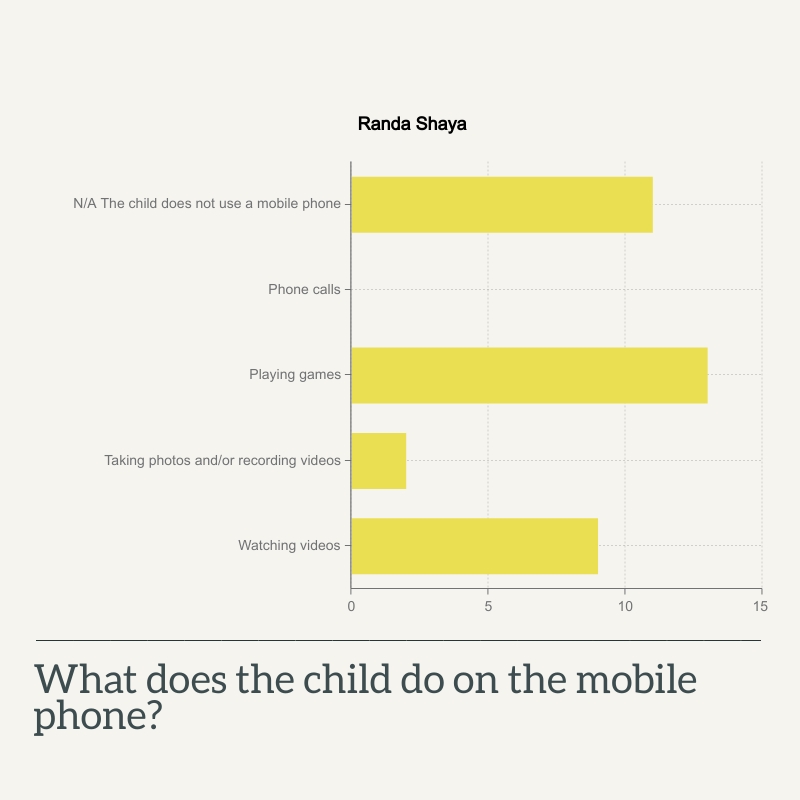

4. Most children use mobile phones to play games and watch videos and some watch television

Half of the children in Randa Shaya use mobile phones to watch videos, just over two-thirds of whom use the phone every day. When asked by the lead researcher, all of the children were able to open either the video gallery on their mobile phone or the Facebook and YouTube applications. Children watch videos through these methods, as well as on television using a USB. Most children report watching funny videos, cartoons, Quran-related videos, and traditional Zawamel songs. One girl showed the lead researcher how she types “children’s songs” into YouTube and other girls showed videos on how to dance, videos for sing-along songs, and one watches “YouTubers.” Two of the boys typed “fighting videos” and showed the lead researcher the violent videos that they watch.

Around one-third of interviewees have a radio and one-third have a television. Children tend to watch cartoons, Quran programming, educational programming, and traditional songs by Ansar Allah (the Houthi Administration), also known as Zawamel. Eight children report listening to the radio, all of whom listen to Zawamel songs, which are thought to encourage people to fight in the civil war.

All parents and caregivers in Randya Shaya are very concerned about children’s access to inappropriate videos, limiting use due to this and due to cost.

5. Most children in Randa Shaya do not attend school

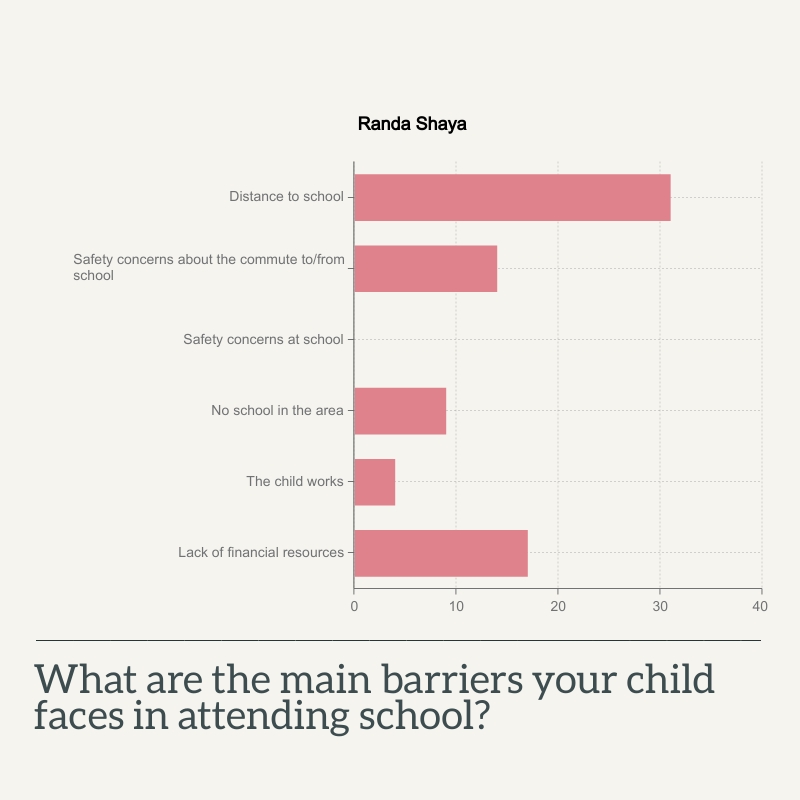

Most children are not attending school as there is no public school in the area and parents and caregivers cannot afford to send their children to the private school which is five minutes from the camp. Many children work to provide for their families. Five of the 36 children interviewees are enrolled in the nearby private school, all of whom are boys. Parents and caregivers feel that girls would not be safe going to school because of the distance, and one parent noted that sending their boy is a higher priority as when he gets married, he will need to provide for his family.

What Does this All Mean?

The significant difference in children’s access to technology between these locations highlights the importance of working with target audiences to understand their access constraints. Understanding the barriers and opportunities to accessing technology, connectivity, and virtual learning and videos in Yemen and the two other focus countries (South Sudan and Colombia) will guide how Sesame Workshop determines the best technology solution for a given context. The next phase of this project will take these findings and develop a framework to guide the decision-making process and lead to the appropriate choices in technology solutions, methodologies, and partnerships to distribute this content blocks in crisis-affected communities.

Sesame Workshop’s Play to Learn is an innovative humanitarian program from Sesame Workshop, BRAC, the International Rescue Committee, NYU Global TIES for Children, and the LEGO Foundation that harnesses the power of play to deliver critical early learning to children affected by the Rohingya and Syrian refugee crises. Through a combination of educational media and direct services, Play to Learn reaches families in their homes, health centers, play spaces, and via mobile phones—providing the tools needed to promote nurturing care and help children learn and thrive. In collaboration with independent evaluator NYU Global TIES for Children, we are measuring the program’s impact on children’s development and caregivers’ mental health and well-being. By sharing what we learn and advocating for increased prioritization and investment in early childhood interventions in crisis contexts, we are laying the foundation to transform how the world supports children affected by crisis, wherever they may be.

Thank you to our lead researcher Abeer Alabasi and her team of enumerators for conducting this research!