Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Drone Mapping Reflects Solid Waste and Ocean Plastic Impact of the Durban Floods

Jun 1, 2022

Heavy downpours over only two days in April 2022 caused South Africa’s worst and most deadly natural disaster to date: a flash flood so rare and devastating it has a one in the 300-year probability of recurring. According to the European Union, approximately 435 people died and up to 41,000 people were affected. Rescue and disaster response efforts, which began immediately, are ongoing.

Cyril Ramaphosa, the president of the Republic of South Africa, declared a state emergency one week after the heavy downpour. Ramaphosa detailed a multi-pronged approach centered on humanitarian aid, housing displaced people and restoring services, rebuilding major infrastructure, and embedding measures to protect residents in vulnerable areas from adverse weather events in the future.

On April 18, when the state emergency was declared, I began leading geographic information systems (GIS) and drone flight operations in Durban, South Africa, to assess the damage the floods caused. From the reports, I knew floods jeopardized structural integrity and public safety. As a waste management specialist, I wanted to see firsthand and understand better what the floods did to the dumpsites, landfills, and low-lying informational settlements. Specifically, I was curious about the environmental impact on low-lying informal settlements and dumpsites. What risk might the damage to waste management sites pose to the public and service delivery?

Aerial image of a broken bridge in Umlazi. Photo: DAI and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team.

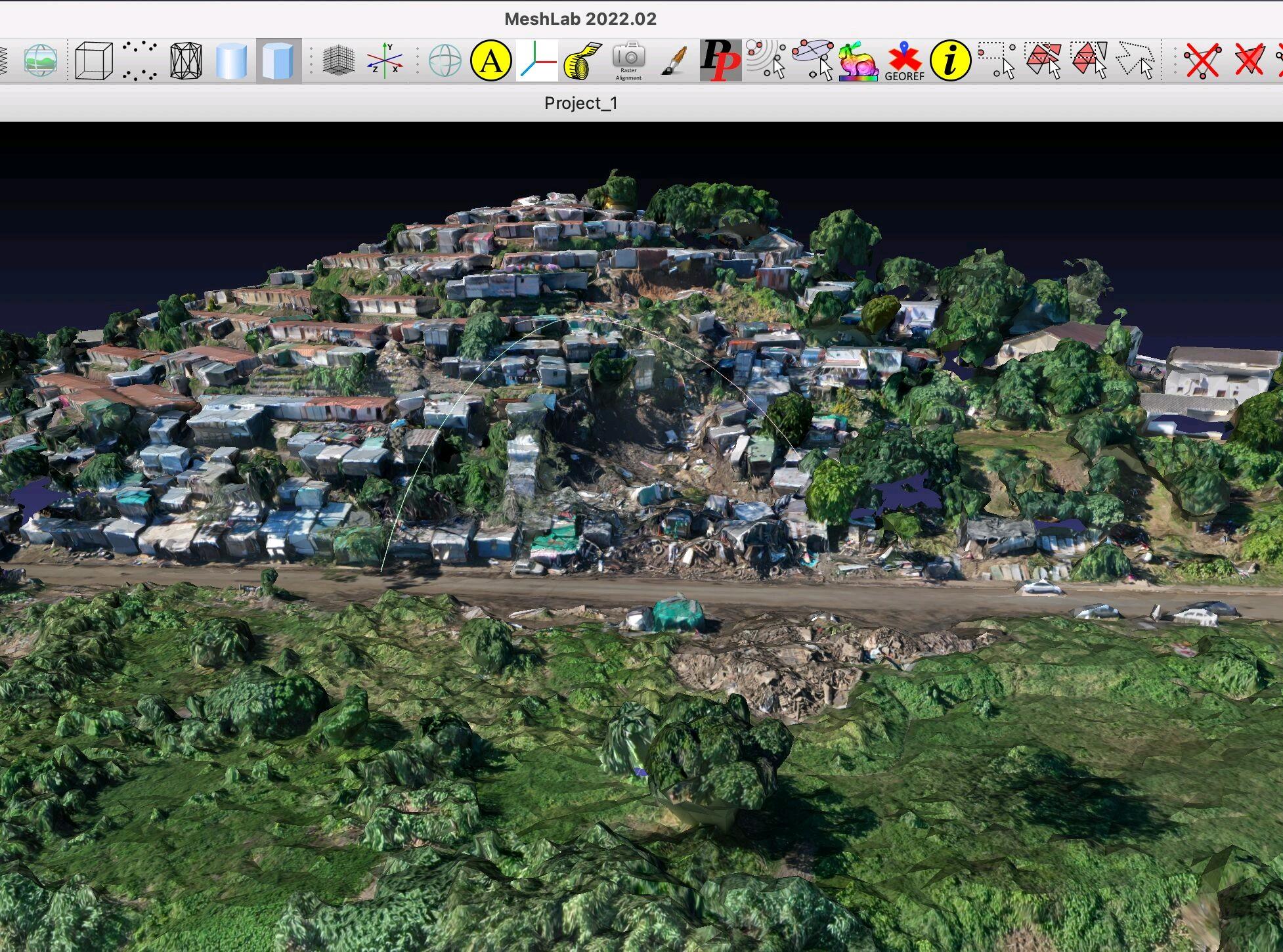

From groundwater contamination and leachate runoff, the disaster exposed persistent environmental and public health issues in Durban and surrounding areas. With housing developments built on sand dunes that have collapsed, there are also landslide risks. The plastic pollution in the Indian Ocean, which was already an existing problem, worsened overnight. The aerial data we captured right after the flood shows these and other consequences up close and in detail. In collaboration with Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team, DAI flew consumer-grade drones such as Mavic Air 2 using simple mobile applications such as Pix4D Capture and OpenDroneMap, as well as QGIS and MeshLab which are open-source computer processing software. This helped us generate extremely high-quality images with resolutions up to 10 centimeters.

Image of Durban natural disaster processed via MeshLab. Photo: DAI and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team.

The drones offer far more than aerial photos or videos of the flood damage. We were able to map the impact, including on the topography, in 3D. The results include detailed renders of a broken riverbank at an informal settlement hard hit near the Springfield industrial area and the damage to infrastructure, such as a wrecked access road to Buffelsdraai landfill. The real-time imagery generated from the aircraft and drones soon after the downpour was otherwise unavailable. The images produced by DAI and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team can be used to help policymakers design effective solutions. From engagements with government personnel, I have learned the metropolitan municipality relies on dated satellite imagery taken before the floods.

Our team paid special attention to the disaster’s impact on formal and informal waste transfer, materials recovery, and landfill infrastructure in the city. The output could be of broader value to administrators, environmentalists, frontline responders, insurers, researchers, and national, provincial, or local government departments. They could include disaster management, water and sanitation, waste removal, and housing.

Already, this project in its infancy has prompted overwhelming interest, across the public and private sectors. Within hours of sharing preliminary work on this project the general public in South Africa, the local government in Durban, and the global OpenStreetMap community responded. The many responses to even the earliest data we gathered suggest a keen interest in our research and an appetite for further data. More than 20,000 people have interacted with an initial LinkedIn post on our efforts, shared on the first day of the field trip. The vast majority of these individuals are based in three South African metros: eThekwini, Johannesburg, and Cape Town. In just one week more than 200 individuals, public institutions, and private enterprises across the open-source mapping community and donor sector both in South Africa and worldwide have reached out to collaborate and crowdsource support services.

Ocean Plastic Waste. Photo: DAI and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team.

We’re now in a position to share all of our raw data, the methodology that we used, and technical guidance on its replication. All of this data is shared under an ODC Open Database License. This means that you are free to use it for whatever purpose desirable, as long as the datasets you subsequently create are also made publicly available. All of our data is regularly updated here.

With special thanks to Sandile Mbatha, Ph.D., Ajiv Maharaj, eThekwini Municipality South African National Space Agency Departments: Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs University of KwaZulu-Natal Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team.