Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Digital Literacy Series: Closing the Gap for Semi-Literate and Illiterate Populations

This post is one of a series of posts on Digital Literacy.

Jul 21, 2022

Last month, the Center for Digital Acceleration launched a series dedicated to digital literacy in international development. We want to learn more about this nuanced topic because digital literacy is central to sustaining the rapid digitalization that has taken place over the last two years. As donors, implementing partners, private companies, and government agencies invest in the digital transformation of key sectors and services, practitioners must prioritize helping the communities interact with digital technology “confidently, critically, and safely.”

Over the last year, I’ve had the pleasure of learning how international development projects can achieve this goal. While conducting research for the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Digital Literacy Primer, I learned how important it is to design digital literacy activities that meet users where they are. A university student looking for an office job, a government official expected to adhere to new cybersecurity policies, and a farmer looking to use his mobile phone to diagnose crop diseases all have different contexts and needs that will shape how a practitioner supports a digital literacy journey. Recognizing the importance of developing unique strategies to serve these unique user groups, one question lingers in my mind: How can we support digital literacy among users who are not literate?

Before we dive in, are you new to the concept of digital literacy? If so, I highly recommend reading the first post of this series to learn more about the concept and how frameworks such as the European Union DigComp Framework can help development practitioners categorize the skills, knowledge, and attitudes needed to develop digital literacy. Another recent post, “Defining and Exploring Digital Literacy in Digital Development,” is also a helpful resource that shares how USAID defines digital literacy and how the USAID-funded Digital Frontiers program is incorporating digital literacy activities throughout its portfolio.

Photo: Images of Empowerment.

Supporting Digital Literacy for the Illiterate

Those with the privilege of growing up knowing how to read and write may not immediately recognize how much these skills have helped them develop their digital literacy. Tasks such as sending a text message, making a phone call, using a search engine, or sending a digital payment form the foundation of many digital competencies and require basic literacy and numeracy. While massive gains in education have helped raise literacy rates above 85 percent globally, according to United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 773 million adults—primarily women—are still illiterate. As a sector intentionally concerned with digital inclusion and closing digital divides, ensuring illiterate and semi-literate users are still able to develop digital competencies and keep up with quickly transforming economies is a goal we should all strive to achieve. (Note: Throughout this piece, I use the terms “illiterate,” “low-literate,” and “semi-literate” to acknowledge the tiers of literacy).

So how do we do that? While each geographic, cultural, social, and economic context will require a different approach, the items below provide suggestions on how to develop programs and tools that are inclusive of illiterate and semi-literate people. (Note: You will find that many of these recommendations focus on how to design inclusive tools rather than specific training approaches. While training and social behavior change activities are important, users cannot develop their digital literacy skills if they don’t have digital tools they feel comfortable using.)

Design With—And For—the User (Surprise!)

If you’re a digital development practitioner (or just a frequent reader of the Digital@DAI blog—thanks for your support!), you’re probably tired of hearing this particular piece of advice. However, it is a recommendation that begs repeating. As Revi Sterling points out in her incredible post, “Why Women Aren’t Using Your Ag App,” though new mobile applications and digital platforms abound in the development sector, users often do not adopt them at the rate we’d expect because they are not designed with their realities in mind: their ability to afford data, their current access to devices, their literacy rates, their information needs, their incentives, their levels of trust and confidence in digital technology, their perceptions and behaviors around privacy and ownership—the list goes on and on.

As such, if we hope to be inclusive of illiterate and semi-literate users, we must put the same effort into designing with and for them as we would for those we perceive as more advanced or sophisticated users.

Research tools such as digital ecosystem assessments, as well as design research strategies like surveys, focus group discussions, observational research, user interviews, user-centered design workshops, card sorting, and A/B testing can all be valuable approaches to learning more about this user group and engage them in product, activity, or training design.

For those without the resources to conduct such analysis, UNESCO’s Guidelines on Digital Inclusion for Low-Skilled and Low-Literate People offer some general insights to be aware of (see page 11 of the document for their write-up):

- Low literacy is not just an inability to read. The lack of academic opportunities that result in an individual not knowing how to read, write, or count, can also impact the development of other cognitive skills needed to develop digital literacy. Examples include understanding information hierarchies like those we often see in menus on apps or websites.

- Low-literate users are scared and skeptical of technology. Users sometimes lack confidence when using digital tools due to fear of breaking the device or a desire to avoid embarrassment (I think we can all relate to this. Very few people feel comfortable saying that they don’t know or understand how to do something!)

- Low-literate users don’t use technology alone. Target users that are semi-literate or illiterate, may be more likely to live in communal societies. This means they may be more likely to share devices and adhere to social norms about technology access and trust.

- Low-literate users are divided by gender. Countless studies show that in many contexts, women are less likely than men to be literate or numerate, own a mobile phone, develop digital skills, or have access to digital devices and services. As women make up two-thirds of the population of illiterate people, digital literacy for semi-literate and illiterate people is inherently a gender issue. (Related: I enjoyed this report from IDEO and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation on specific design considerations to encourage women to use financial services.)

- Low-literate users are driven by motivation and aspiration. While conducting research for the USAID digital literacy primer, I repeatedly heard that if a user sees the value of a digital tool or device, they will take the time to learn how to use it (barring systemic obstacles such as accessibility, availability, and affordability). The UNESCO guidelines find that hopes for better livelihood outcomes can significantly motivate low-literate users.

- Low-literate users are often resource-constrained. Access to the internet, data, and devices can all be quite unpredictable (or predictably challenging) for this group of users, requiring solutions that are accessible even when new barriers arise (example: online and offline capabilities).

Prioritize Accessibility

During an eye-opening Mozilla Fest 2022 session called “Digital Experiences for Overlooked Literacies,” host Uluwehi Mills explained to attendees that written literacy, often regarded as a “measure of intelligence and mediator of knowledge transfer” in a world increasingly dominated by Western values, is just one of many different types of literacies. Overlooked literacies include the spiritual, sartorial, olfactory, linguistic, gustatory, or iconographic. One of the most exciting ideas I took away from this session is that literacies, lettered or otherwise, represent different interfaces that we can use to inform and shape our interactions in the digital world. Lettered interfaces are not the only option but are prevalent across our applications and platforms. While we haven’t quite figured out what a gustatorial interface might look like in the digital world (though I really look forward to this day), designers are already making use of iconography and other visually based literacies.

The UNESCO guidelines support this approach, recommending interfaces that leverage icons, color, photos, and other graphics over text. While this may seem straightforward enough, designers and digital development practitioners should take the opportunity to develop interfaces that are not only accessible to semi-literate and illiterate users but also to those that are culturally sensitive. Not all colors, icons, and graphics mean the same across cultures. For example, as Cynthia Risse notes in her Medium article on cross-cultural design, while black is considered the color of mourning in Western cultures, white is regarded as a color of sadness, death, and mourning in some Eastern and Slavic cultures. Graphics, photos, and illustrations should not only be culturally relevant, depicting local people, landscapes, and scenarios, but culturally sensitive so as to not offend or communicate unintended messages. In their paper, “Text-Free User Interfaces for Illiterate and Semi-Literate Users,” Medhi, Sagar, and Toyama found that research subjects more easily recognized semi-abstract and photorealistic graphics as a visual representation for certain actions but that, at times, religious or cultural differences impacted how graphic elements were interpreted.

Integrate Trusted Human Interfaces

Another exciting thing about promoting digital literacy among semi-literate and illiterate users is the opportunity to integrate digital and analog worlds. Through longstanding digital capabilities such as interactive voice response, voice-to-text, audio, and video content, as well as emerging technologies such as voice computing via artificial intelligence assistant, digital tools can leverage human interaction to reinforce new skills and behaviors.

Digital tools or services that require or encourage engagement with trusted human interfaces such as mobile money agents, extension officers, helplines, savings groups, cooperatives, or other social networks can encourage users to build new competencies and recognize the value of these tools. While conducting research for the USAID Digital Literacy Primer, I found that integrating human interaction through the above-mentioned intermediaries was a common approach used across various sectors, especially in sectors like agriculture and health, where users value social networks and in-person interaction to build trust and confidence.

Don’t Forget About Numeracy

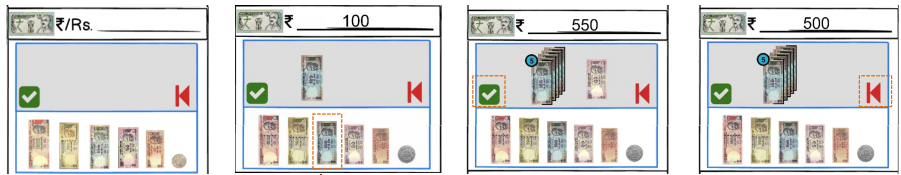

While many of us may think of numeracy simply as the ability to do basic arithmetic, it encompasses several skills that are necessary for economic, social, and political participation. Numeracy is needed to develop financial literacy and to complete certain workplace or vocational tasks. It is even necessary to safely manage one’s health and interactions with the healthcare system (example: Knowing how many tablets to take or measuring the proper dosage of a medication). As with literacy, adults without these skills are still able to get by in life, for example, by knowing the value of banknotes by their color, but not necessarily by their numerical representation. However, not understanding numerical concepts like decimal point placement could be risky for innumerate users exploring digital financial services. When exploring what digital options are available for innumerate users, I came across some research from MicroSave and MyOralVillage on digital financial services for oral populations. They found that a cash-based input method (versus a numeric or alphanumeric input method) was more easily accepted in testing with oral users, and mistakes were more easily identified. I am excited to see how other visual cues and input methods can be used to expand the use of digital services in areas outside of mobile money and digital banking.

Types of Input Method Editors. Image: MicroSave & My Oral Village.

Cash-Based Input Method Editor. Image: MicroSave & My Oral Village

Don’t Shy Away from “Advanced” Skill Development

When reviewing the DigComp Framework’s core digital competencies, one may quickly realize that some skills could be considered more “advanced” than others. For example, information and data literacy, which includes skills like browsing, searching and filtering data, may seem less challenging than digital content creation, which requires not only skills in information and data literacy, but additional skills such as integrating digital content and programming. While all these different skills are necessary to develop digital literacy, the USAID Digital Literacy Primer highlights that resource constrained projects must carefully consider which digital skills to prioritize based on what is of most use and relevance to a target user.

While one may think of digital safety skills such as protecting devices, personal data, and privacy as an advanced skill set that may be beyond the immediate needs or capacity of a semi-literate or illiterate user, there are pathways available. For example, promoting pin numbers or strong alphanumerical passwords as the only options to protect one’s device or account could be challenging for users that are not familiar or comfortable with alphanumeric or numeric input methods. In some cases, this practice could actually present new risks. A 2019 report from IDEO and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation on the financial agency of women in northern Kenya found that mobile money agents were encouraging women with low literacy levels to use their year of birth as their pin number. This resulted in women carrying around their identification more frequently or handing them over to agents to input the date on their behalf. This creates risk of a security breach or simply losing one’s identification. The report identified alternative verification methods such as voice recognition as a potential solution. Interviewees I spoke with for the USAID Digital Literacy Primer also identified using colors and photos as alternatives to alphanumerical passwords. This demonstrates that with some creativity a wide range of digital literacy skills and behaviors can be established.

Learn More

Supporting digital literacy among illiterate populations heavily relies on using tools that are thoughtfully designed. While it may be tempting to think of digital literacy in international development purely as an exercise in developing targeted training and instruments to measure progress over time, it is just as important to ensure that user groups have access to tools and services that they can use with ease and that allow them to build confidence over time. Hopefully, the suggestions above help inform any digital development projects that hope to include semi-literate and illiterate populations.

If you’re interested in other solutions digital development projects have employed to serve low-literate people, check out UNESCO’s landscape review.