Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Digital Literacy Series: The DigComp Framework

This post is one of a series of posts on Digital Literacy.

Jun 14, 2022

With the onset of the pandemic spurring ever-faster digitalization around the world, we at DAI’s Center for Digital Acceleration are thinking about the key elements needed to ensure sustainable digital transformation in the countries where we work. One of the primary building blocks needed to achieve sustainability is strengthening digital literacy. As digital development practitioners, digital literacy is a big part of our work. Whether a person is getting online for the first time or is a cyber specialist, we have a responsibility to ensure those we work with have the agency to use the appropriate technology meaningfully: to achieve professional and personal goals, while avoiding digital harm. We also have a responsibility to close the digital divide by supporting novices in developing basic skills, so they are not left behind.

As we noted in a previous blog, digital literacy is an amorphous term that encompasses so much more than basic digital skills. It includes a wide range of skill sets and competencies, including media literacy, digital financial literacy, and identifying mis- and dis-information. To make things even more complex, as the technological space advances, so too does the scope of, and requirements for, digital literacy.

With so many different digital skills and competencies to consider addressing in development programming, it often feels overwhelming to know where to begin. Luckily, numerous frameworks have been created to define and create a common language for digital literacy, including the Digital Literacy Global Framework, the DQ Institute Framework for Digital Intelligence, and the European Union Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp), among others.

As one of the most comprehensive frameworks for digital literacy and having been drawn on for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)’s digital literacy primer, we wanted to dig more into DigComp to better understand how it applies to our work in international development. This blog is the first in a series focused on the applicability of the DigComp Framework to the international development community.

Photo: Unsplash.

Introducing DigComp

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp) was created more than a decade ago by the European Commission through stakeholder consultations, to provide a common understanding of what digital competence is and act as a basis for framing digital skills policy. It is sector- and technology-agnostic and up to users to tailor and adapt the reference framework to their needs when designing interventions.

While DigComp was developed by the European Commission to help its citizens “engage confidently, critically, and safely” with digital technologies, by defining digital literacy, DigComp provides the development community with a common understanding and language needed to incorporate digital literacy more intentionally into our programming. Frameworks such as DigComp can help us clarify what range of skills need to be developed, and prompt us to think about how best to track progress over time. Recognizing the responsibility of development practitioners to support digital literacy among the populations with which we work, USAID recently launched the Digital Literacy Primer, which defines digital literacy and lays out how it contributes to the global development goals. The primer recognizes that there is room in all digital-facing development programs to contribute to building digital skills. The primer uses DigComp as a comprehensive framework for understanding digital literacy, demonstrating the benefit of the Framework for our sector.

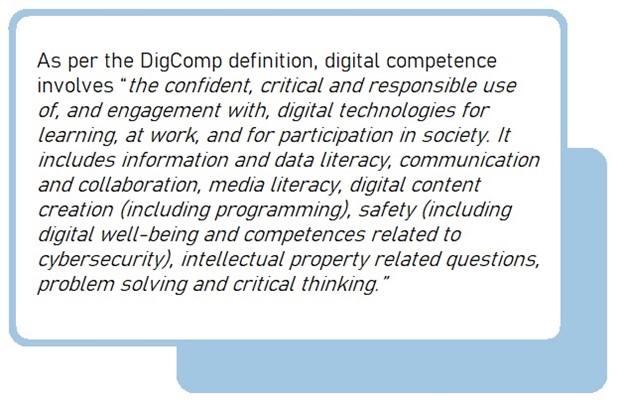

Definition of digital literacy as per the European Union Digital Competence Framework for Citizens 2.2.

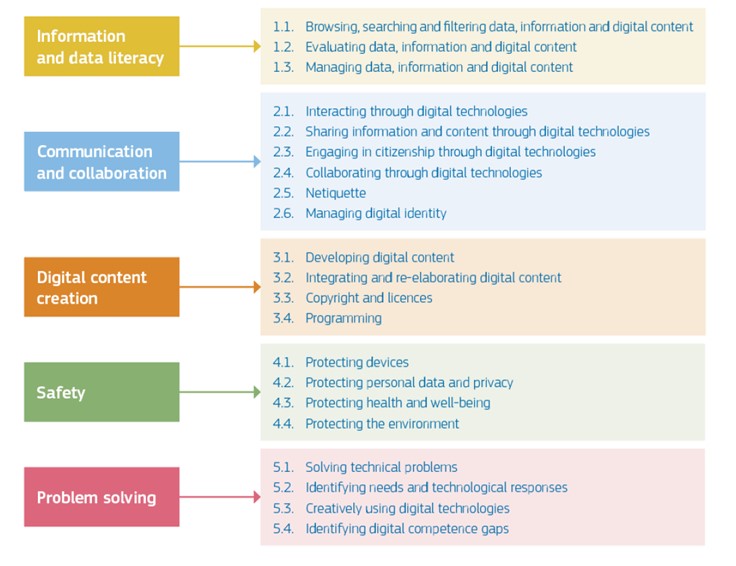

DigComp lays out five digital competence areas and a total of 21 digital competencies. The digital competence areas include information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem-solving. The competencies include specific activities (such as searching for digital information, creating content, and communicating online); and transversal competencies that apply to all online activities (safety and problem solving).

DigComp Conceptual Reference Model 2022.

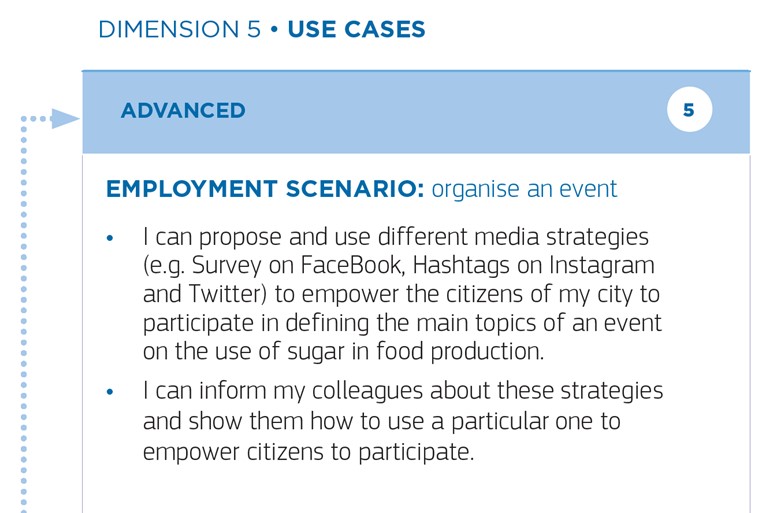

In its most recent update, DigComp takes into consideration the ever-changing digital space, and the increasing digital literacy requirements these changes place on citizens. DigComp 2.2 now includes examples of knowledge, skills, and attitudes for each competence area, that are needed to navigate a complex digital world. For instance, requiring knowledge of the Internet of Things (IoT) and its applicability to one’s life, having the skills to complete more advanced tasks such as using IoT devices to create content, and having attitudes such as the willingness to weigh the benefits of giving permissions to a device to access your location. It provides examples for different scenarios, such as what collaborating through digital technologies looks like in work and education settings.

DigComp 2.2: Competence 2.4 Collaborating Through Digital Technologies, Use Cases, page 21.

How Can the International Development Community Use DigComp?

DigComp can help us identify where we might already be doing digital literacy. Digital literacy is so complex that it might not always be clear to practitioners where it is already part of existing programming. We can use the DigComp Framework to identify which activities are helping build digital literacy and use this knowledge as a basis for information sharing and finding best practices.

The development community can also use the framework to design programming, and in doing so will be guided to consider the full range of digital literacy competencies. Armed with guidance on the complex nature of digital literacy, users can design comprehensive digital literacy curricula which include finding and managing information, communication, and collaboration through digital technologies, creating content, keeping safe online, and problem-solving.

The framework provides us with a common definition of digital literacy, which will not only help the development community recognize where we can contribute to building digital skills but also allows stakeholders to monitor progress and share knowledge and best practice on digital literacy policy and implementation more easily.

How Can We Make DigComp More Applicable in International Development?

DigComp was developed to help the European Union in digitally upskilling its population. The European Union is, of course, a region with a high proliferation of advanced digital tools that has near to 90 percent uptake of mobile phones, and 82 percent of the population using mobile internet. In contrast, the populations with which the development community works often have lower levels of mobile phone penetration, struggle with issues such as poor connectivity, low affordability, and literacy, and may have lower average digital literacy levels. We implement digital programming with a wide range of communities—we may be working with women and girls in remote Malawi who are illiterate and only use mobiles for phone calls, or with tech-savvy entrepreneurs in Cambodia.

The framework was designed to be agnostic to technology type and outlines competencies from foundational to highly specialized. For instance, Competence 2.2 Sharing through digital technologies refers to a person’s ability to share data, information, and digital content with others. At a foundational proficiency, a person can, with guidance, recognize simple appropriate technologies to share data. For example, with the support of a friend, they can use WhatsApp to send a photo.

However, the examples in the most recent iteration of the framework were written to be most appropriate to the most recent technological developments. The development community’s work focuses more often on less advanced levels of competency, and with more basic technologies. Although the examples in the DigComp update are not meant to be a set of learning outcomes, the digital development community may want to create more applicable examples to make the framework more operational for us. These examples can help us to contextualize the framework for our work, and help us to set realistic learning targets for users in the markets where we work.

Where Does Trust Fit In?

When reviewing the DigComp Framework it was notable that trust is not considered a digital literacy competence, although many of the competencies require knowledge of methods to keep oneself safe, the skills to do so, and an attitude of vigilant and proactive self-protection. Trust is a key factor in the uptake of digital tools; you are unlikely to use a digital financial product unless you can be confident your money is safe. Trust can be a result of digital literacy—DAI research among internet users in Ghana found that users trusted the social media platforms they used, as they felt they had control over their password and decided what information they wanted to share publicly. However, trust can also be a result of social norms or external influence. Our research in Ghana found a peer effect of trust—if apps were popular and used by many of their friends, people felt comfortable trusting them. It would be difficult to lay out this complex relationship between digital literacy and trust in any digital literacy framework. DigComp provides a series of competencies that cover the skills, knowledge, and attitudes needed for a person to understand the risks of using technologies and how to protect themselves. As noted in the USAID Digital Literacy Primer, programs will need to be on the lookout for other drivers of trust and focus on how trust can be built, whether through learning to mitigate digital harms, identifying trusted digital services and platforms, and building familiarity with digital tools.y

What Next?

DigComp lays out the competence areas of digital literacy in a population-, sector-, and technology-agnostic way. It is therefore fully adaptable to the international development sector’s purposes. Through “design with the user” practices, we will be able to use these competencies to design programming that considers what skills the target audience needs to develop and place these in the local context to support trust-building.

In the rest of this series, we will delve into each of the five competence areas, to further examine their applicability to the international development sector.