Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Top 5 Civic Tech Concepts and Ideas from PDF 2016

Aug 16, 2016

The annual Personal Democracy Forum (PDF) might best be described as “civic tech prom.” It’s that once-a-year time when civic tech enthusiasts put on their good shoes, stand up in front of their peers, and show how they’re using new technology for public good. What qualifies as civic tech in this crowd? If you’re starting discourse about important public issues, monitoring government expenditures, holding politicians accountable for campaign promises, drafting candidates to run for office, and using a mobile phone, social media, or remote sensing to do it, you would fit right in at PDF.

Wael Gohnim speaking on the impact of social media on political polarization at PDF 2016

While DAI does little work in the purely political sphere—this is NDI’s and IRI’s wheelhouse—we do have a number of projects that work with local governments to improve their ability to manage funds and engage with civil society, as well as increasing civil society’s capacity to hold governments accountable. For example, Nexos Locales in Guatemala and ENGAGE in the Philippines.

I attended PDF 2016 this past June in New York City, seeking to spotlight the work could be most applicable to DAI’s work in local governance and civic engagement around the world. So, with no further adieu, my guide to the top 5 civic tech concepts and ideas from PDF 2016:

#5 Civic tech is for both sides of the aisle

Republican pollster Kristen Solits Anderson makes the point that, contrary to popular belief, data-driven government isn’t just for liberals. Conservatives who criticize “big” government as wasteful shouldn’t just advocate dynamiting the bureaucracy; they should be advocating for more government accountability, and the raft of technologies that are available in support of that goal. In the private sector, accountability comes in the form of the choices we make every day: if Uber isn’t working, we can use Lyft. We can use Yelp to figure out which restaurants are worth visiting, why don’t we have anything like this for government? That’s something that both liberals and conservatives can get behind.

#4 Do you know a woman who should run for public office?

Erin Vilardi does, and she’s betting you do too. She runs VoteRunLead, which drafts women to run for public office. VoteRunLead also offers leadership training for women, features profiles of women who are leaders in local government, all under the premise that a government which better reflects its constituents will better represent them.

#3 Civic tech has a champion in the Middle East

Esraa al-Shafei’s first instruction was “please, no photos.” Apparently being a blogger and civic activist has not endeared her to the authorities in her native Bahrain. But al-Shafei is also the founder of a bunch of cool civic-oriented tech startups. Mideast Tunes is a “platform for underground musicians in the Middle East and North Africa who use music as a tool for social change.” As of August, it includes more than 9,000 tracks from 1,700 artists, and is available online for free. Al-Shafei has also been a primary driver behind Ahwaa, which is likely the only “open space to debate LGBTQ-related issues in the Middle East.” The system features tiered permissions to allow the community vetting of new members and prevent infiltration and co-option by anti-LGBTQ groups. Al-Shafei’s other initiatives are Majal, CrowdVoice and MigrantRights.org.

#2 Civic Tech Field Guide

Among the more practical tools presented at PDF, the Civic Tech Field Guide is a comprehensive listing of U.S.-based civic tech projects, organized according to type: crowdfunding, citizen government communication and vice versa, voter registration, ideation, etc… The Field Guide is currently in Google Sheets format, meaning that anyone can add new projects or make comments (be careful not to delete anything that you didn’t add). For anyone with an interest but lack of experience with civic tech, reviewing the Field Guide is a great place to start. For anyone working in civic tech, the Field Guide is an excellent resource for best-in-show examples of what’s already being done in the field. The Field Guide is the work of Erin Simpson of Civic Hall Labs, Micah Sifry of Civic Hall, and Matt Stempeck of Microsoft Civic Tech.

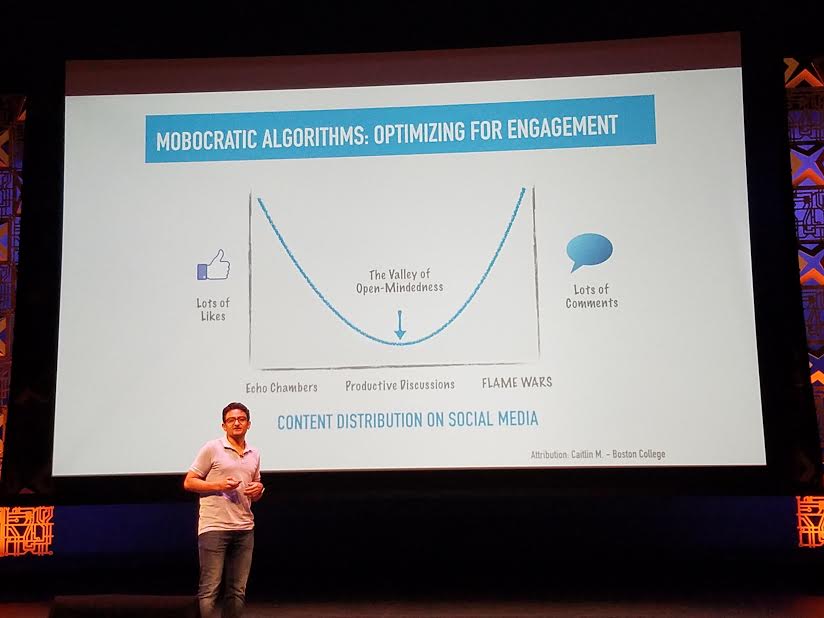

#1 Social media is driving political polarization

One day Wael Ghonim was a Google engineer in Cairo; the next day he was the father of a revolution. It was his effort to set up a Facebook page protesting the death of Khaled Mohamed Saeed that led to broader protests in Tahrir Square, and the eventual abrupt end of the Mubarak regime in Egypt. Since then, Ghonim become a social entrepreneur, founding Parlio, a crowd-sourced discussion platform which highlighted important topics in civic life. His central point at PDF was that our social networks—particularly our Facebook feeds—are a driving factor in the political polarization that currently binds our country. How? The newsfeed is designed to draw our attention by presenting us with information that Facebook calculates we’re likely to agree with. This keeps our attention, keeps us on Facebook, keeps us viewing their ads, and keeps their advertising dollars rolling in. Facebook has been tweaking their algorithm as of late to reduce the amount of useless click-bait users see, but the social value of a idea of a more ideologically diverse newsfeed does not seem to outweigh the financial incentives of a more curated one.

One of the best illustrations of Ghonim’s point is a recent article in the Wall Street Journal that illustrates how people who Facebook views as political opposites would end up seeing the same news story. Generally, the blue, or liberal newsfeed is filled with stories from the Huffington Post and RawStory, while the red, or conservative newsfeed is filled with Breitbart or Fox News stories. The net effect is that—unlike previous generations who had only three options for the nightly news—today’s media consumer no longer receives a newspaper, is more likely than ever to have cut the cable wire, and receives most of their news coverage from their Facebook newsfeed. This dynamic is not inherently harmful, but it opens the door for dangerous polarization of information in a political environment where demagoguery has become the standard.