Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

What Do You Get When You Combine Digital Infrastructure, Skills, and Trust with Affordability and Device Access? Introducing Our Concept of Digital Readiness

Aug 31, 2023

DAI’s Center for Digital Acceleration (CDA) has done many deep dives about different topic areas on Digital@DAI over the years, from digital skills, digital trust, and digital infrastructure to affordability and access. For the first time ever, I am going to bring them all together under the umbrella of “digital readiness.” Before we get there, however, I want to acknowledge that CDA is not the first organization to come up with its own definition for this term. How have others defined digital readiness?

- At the country level: More specifically, the United Nations Development Programme’s Digital Readiness Assessment (DRA) looks at “inclusive, whole-of-society digital transformation” at the country level along five pillars: infrastructure, government, regulation, business, and people. Similarly (arguably), the Network Readiness Index (NRI) ranks countries against the pillars of technology, people, governance, and impact to identify “the most-network-ready societies.” The readiness pillar of the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Inclusive Internet Index takes a relatively zoomed-in view compared to the DRA and NRI, analyzing country-level literacy, trust and safety, and policy to “examine the capacity to access the internet.”

- Sector specific: Several organizations have also put out sector-specific readiness indices, scales, and analyses. On the digital government side, for example, the World Bank’s Digital Government Readiness Assessment looks at public sector readiness for digital transformation within a specific country. In terms of economic growth, Cisco’s Digital Readiness Index measures “overall readiness to foster an inclusive digital economy” at the country level, while the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s e-Trade Readiness Assessments do largely the same for country e-commerce ecosystems.

- At the household or citizen level: This category is arguably the most like DAI’s definition of digital readiness (see below—what an intense build-up!). For example, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 2021 Framework for Developing Digital Readiness Among ASEAN Citizens highlights three elements critical to its conception of digital readiness: digital access, digital literacy, and digital participation. Developed to survey Americans about their levels of digital readiness in 2015, the Pew Research definition of digital readiness examines digital trust, skills, and use. Similarly, a 2018 Purdue University paper developed a Digital Readiness Index for quantitative research in the United States, measuring device and internet access, digital resourcefulness and utilization, and internet benefits and impact.

So, after all that context, how does DAI’s Center for Digital Acceleration (CDA) define digital readiness? “The ability and desire to use digital technology.” Many existing definitions of digital readiness can only be applied to a specific group of users, and we think that this needs a more flexible approach. Our simple and flexible definition can apply equally to—or be adapted for—any of our typical target user groups, ranging from individual citizens to micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) to government agencies and beyond. Many digital readiness definitions also seem to assume that a user’s desire to use digital tools equals their technical ability to use these tools, but this is not always true. Our definition uncouples these two distinct concepts, setting it apart from other definitions that we have seen.

How Do We Measure Digital Readiness?

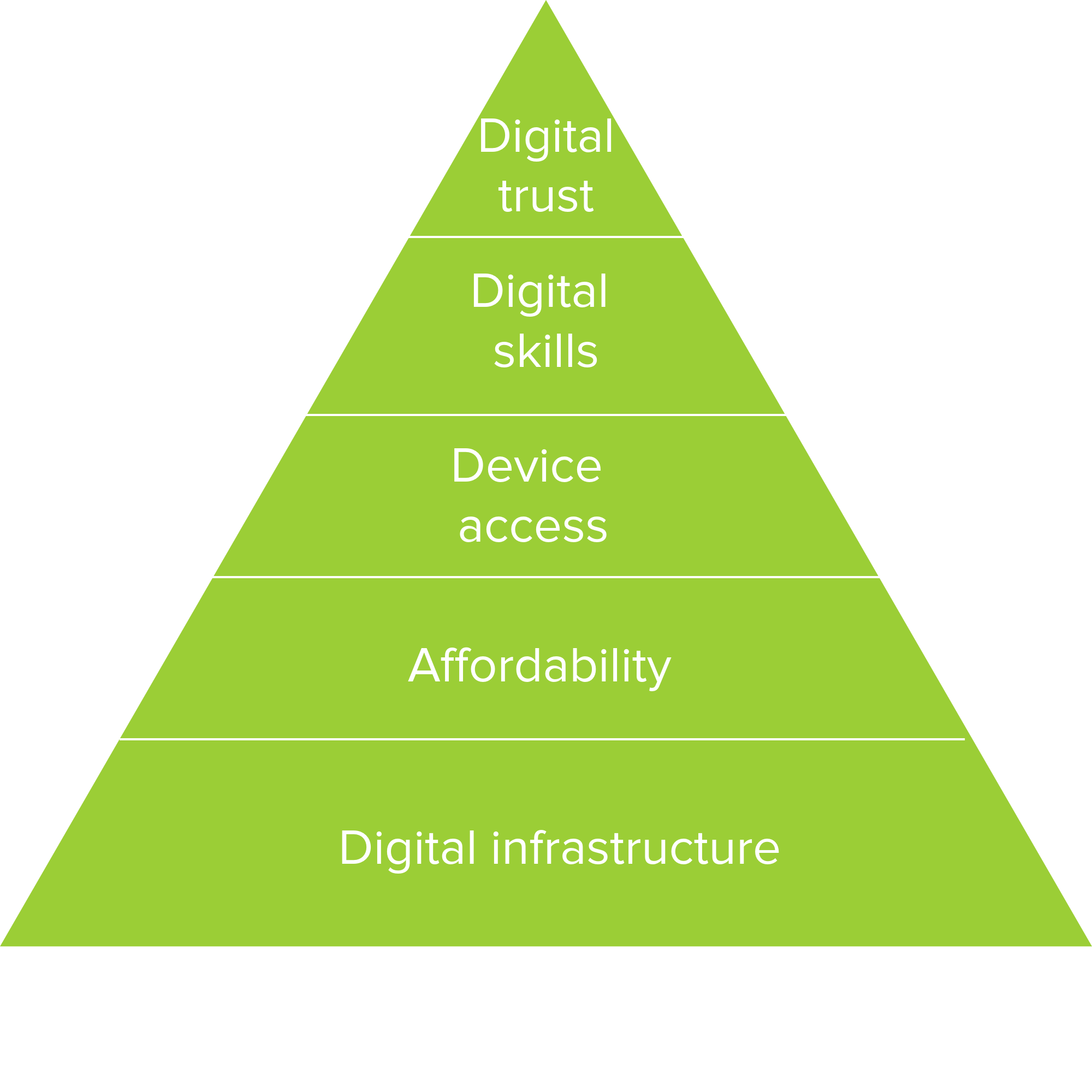

We look at five different enablers that we consider prerequisites for any kind of meaningful digital tool use:

- Digital infrastructure—Is consistent, high-quality internet access available within our geographic area of interest? If yes, can our target users physically access it, including traditionally marginalized groups like people living in rural areas? Target users who meet these criteria for digital readiness will have regular access to high-speed and high-quality broadband internet.

- Affordability—Can our target users afford a device? Can they afford access to data and/or broadband? Can they afford the other enabling factors for internet access, such as consistent electricity? How does this differ among vulnerable groups, such as people with disabilities or people with low or no incomes? Target users who meet these criteria for digital readiness can afford access to a digital device and to consistent, high-quality broadband.

- Device access—Can our target users access or own digital devices such as feature phones, smartphones, or computers? Do social norms enable or prevent some or all of them, like girls and young women, from using these devices? Target users who meet these criteria for digital readiness will have regular access to—or own—a feature phone at a minimum.

- Digital skills—Do our target users know how to use their devices and other relevant digital technologies, such as social media? Are they allowed to acquire new digital skills, particularly for women, girls, and other vulnerable groups? Do they want to cultivate new digital skills to use digital tools? Do they feel confident in their skill levels? Target users who meet these criteria for digital readiness will understand how to use, and feel comfortable and confident in using, the features of their digital devices and associated digital tools required for the intervention or for the target activity.

- Digital trust—Do our target users believe that digital tools and technologies will compromise their physical or digital safety—especially among marginalized populations, such as the LGBTQI+ community? Do they believe that using digital tools will improve their quality of life? Target users who meet these criteria for digital readiness believe that their digital devices and tools will not harm them and can add value to their everyday lives. To show how each enabler builds on the others to create or signify digital readiness, we are currently using a pyramid structure. In this hierarchy, each building block requires the one below it—for example, device access requires affordable devices, which require digital infrastructure for internet access. We like the concept for its simplicity and cleanness. However, a pyramid structure can also obscure the complex interplay among these digital enablers. For example, a lack of digital trust could mean that individuals choose not to acquire digital skills. Because of this complexity, we may eventually move away from the pyramid shape in favor of a different “digital readiness” visual.

How is Our Definition Different?

Now that I have clarified CDA’s working definition of digital readiness, our five different digital enablers, and how they relate to one another, let’s talk about what sets our definition apart from the other definitions out there. (Let me clarify that I do not have ChatGPT-like abilities and have not read every single definition of digital readiness out there but based on my own research.)

- It is user-centric. We focus on the digital readiness of individual users or user groups at the micro level, rather than taking a macro-level view of a specific country’s digital readiness, as is more common in the digital development sector. (Our definition of digital readiness is closest to that of the other household/citizen-level definitions put out by ASEAN, Pew Research, and Purdue University, but these definitions and metrics often assume that target users can get online, which is not always the case—and directly leads to my next point).

- It couples the ability and the desire to use digital technology. Many digital readiness definitions seem to conflate the ability and the desire to use digital technology—or not even to consider both points at all. However, ability and desire are fundamentally two separate things. Just because someone desperately wants to use digital tools (desire) does not mean that they have the technical means (or ability) to do so. Just because someone can use digital tools does not mean that they want to use them. The target user needs to meet both these criteria to be digitally ready, which—again—leads directly to my next point. Our digital enablers focus on the factors that enable meaningful internet and digital tool usage. Many digital readiness definitions from our sector seem to commingle true prerequisites for digital tool use with “nice-to-haves” that already presume basic digital access. Sequencing is critical here. For example, why measure MSME digital readiness by looking at their adoption of formal digital transformation strategies if they cannot access 4G or cannot access a mobile phone or computer? Being able to access the internet and associated digital devices are (or should be) prerequisites for having a formalized digital transformation strategy, which does not actually measure an MSME’s ability to use digital technology—only their desire. These alternate approaches mix up the factors that enable digital tool use with those measuring the richness and complexity of that use.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Right now, this is just a conceptual framework that concisely summarizes what we at CDA have been thinking about for a long time. If we can, we would like to incorporate it into the projects that we work on and develop more concrete quantitative and qualitative measures of each digital enabler. I would also love to hear from you and get your feedback on the above—does this definition of digital readiness resonate? Have we included the right digital enablers and, more importantly, are we missing any biggies? Is this as different or unique as we think it is? Send us an email at [email protected] or drop me a note on LinkedIn to weigh in.