Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Unearthing Lessons by Revisiting—Not Reinventing—the Wheel by Utilizing Data Science

Nov 14, 2019

As we enter what the World Economic Forum refers to as the “fourth industrial revolution”—a profound transformation of industries and institutions driven by artificial intelligence, machine learning, robotics, and augmented reality—international development practitioners are shifting toward data-centric business practices that require new systems, more efficient work flows, and modern skill sets. While the promise of newly available data is driving a desire to answer new analytical questions, lessons from more than 50 years of development projects lay dormant in Word and PDF documents stored in disparate folders, databases, and online portals by a wide array of stakeholders.

Data science is an approach to gleaning insights from data through advanced statistics and the development of customized code—generally using Python or R coding languages. Just as data science tools can construct insights from new data, machine learning algorithms (or models) can also help to mine hidden institutional knowledge from text using what’s known as natural language processing (NLP). NLP holds potential to analyze and draw trends from the multitude of lessons out there.

The ABCs of NLP

In short, NLP focuses on the interactions between computer and human languages and can be applied to text and speech. NLP is used in systems such as speech recognition, document summarization, translation, spam detection, question answering, and predictive typing, just to name a few examples.

The international development sector has documented its body of knowledge within decades of reports, articles, books, and other documents, generating massive volumes of text. In instances where that knowledge and experience could be most informative—during project design, strategic planning, or stakeholder engagement, for example—it is often untenable for people to locate, read, and analyze existing text-based data to extract relevant trends or other insights. NLP machine learning models transform large amounts of text into numeric values—a process called vectorization that makes the informational patterns in text available for NLP to draw out insights.

The Mechanics

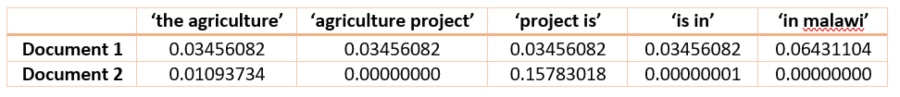

One common method of vectorization works by assigning all of the words in a body of text-based documents—referred to as a corpus—to an enormous table, where each column is a unique term in the corpus and each row is a document. The resulting matrix is populated by a numerical statistic that reflects how important each term is to each document—based on frequency—offset by how common the term is in the corpus. The more common a term is in a corpus, the less likely it is to be important for characterizing any one document. The terms can be either single words (unigrams), word pairs (bigrams), or even larger sequential word groupings from the text. The choice of term size differs depending on use case and relates to the performance of the NLP predictive model to be used. Breaking the following sentence into bigrams, for example, would result in the subsequent column headings:

The agriculture project is in Malawi

Once the documents in a corpus are represented numerically, coded models can train on (or learn) existing patterns in the text. This is done using a training set of text instances—project reports, for example. Once the predictive model is trained, it can be used to approximate the nature of additional documents, based on the characteristics it learned from the training set.

Mining Insights from a Corpus

If an NLP predictive model is trained on a set of project documents that are pre-labeled by development sector—health, education, agriculture, or governance, for example—it will use the commonalities in the text patterns among documents with the same sector labels to predict the appropriate labels for other project documents fed to it. This could be a cache of decades worth of documents sitting unorganized in a P drive or online repository and which are too numerous for people to read and label manually. Other “features” of the document—year, country, or authoring entity—could also be utilized with the model. An incredibly large collection of documents can then be automatically organized into meaningful subsets, on which more refined models can be designed to further analyze and segment. Information and insights long since buried, are suddenly within reach.

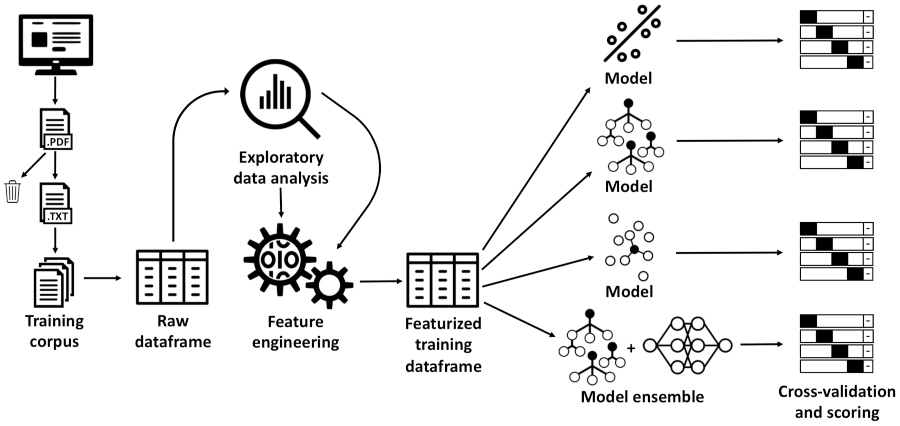

An NLP process flow

The Machine Learning Process

NLP is a tool from the machine learning toolbox. Machine learning is a subset of computer science that utilizes algorithms and statistical models, which rely on patterns and inference to perform a predictive task, typically involving either classification or regression. Machine learning is a broad practice that takes many forms and has many applications. While the code, algorithms, and statistical theory that make up machine learning are complex, the learning processes generally share the following distinct steps.

-

Obtaining data. Whether collecting new data or making use of existing data, data quality and quantity have direct influence on how well a machine learning model can make inferences or predictions. Of course, the data need to be the right data for the question to be answered or problem to be solved. Often a great deal of effort needs to be invested in this step of a data science project, particularly in international development where datasets are generally small, disparate, unstructured, or incomplete. In the case of using NLP for characterizing text-based documents, having the right data means obtaining an appropriately labeled corpus—documents accurately labeled as health, education, agriculture, or governance, for example—for the development sector labels to be predicted by the models.

-

Understanding the data. Machine learning is most often performed on datasets that are too large to simply view or scroll through. With NLP, the volume of documents would be too large for humans to read and identify patterns in the text, like word frequency and topic patterns. This step of an NLP project might include topic modeling or sentiment analysis, where algorithms find abstract topics—kind of like sets of word clouds—or interpret positive or negative tone from the text. Data scientists refer to the getting-to-know-your-data step as exploratory data analysis, and it crucially informs subsequent analytical steps in the machine learning process.

-

Data preparation. Data come in many forms and layouts and most often need to be reorganized and transformed to make it appropriate for predictive modeling. This step is often referred to as feature engineering. In the case of NLP, preparing the data for predictive modeling most often involves converting the text into lists of tokens—words or terms separated by columns, lowercased, and with punctuation removed. Before word tokens are converted to numeric values, stop words are usually removed from the tokenized lists. Stop words are words that are too common to have any predictive value—like ‘a,’ ‘an,’ ‘and,’ ‘it,’ ‘the,’ ‘with,’ etc. Once the data is appropriately transformed, it is loaded into a suitable place to be called on by a machine learning model.

-

Choosing a model. Researchers and data scientists have created many models over the years. Some are well-suited for image data, some for numerical data, others for text-based data. The nature of the data, the problem to be solved, the use case of the resulting prediction, and the time and other resources available for the machine learning project all go into the consideration of which model to use. Often multiple models are trained, and predictive performance is compared between them before a final model is selected.

-

Tuning the model. While technical and grounded in statistics and probability, machine learning is somewhat of an art. Tweaking the code to adjust parameters in the algorithms can be a lengthy and involved step in the process requiring trial and error, persistence, and creative thinking. The nuanced implications for decisions around model tuning need to be communicated clearly and often visually in a consultative process with end users.

-

Prediction. Once a machine learning model is optimally trained and ‘tuned,’ it’s ready to be used for answering questions or making predictions. In the NLP example with international development reports, it means the model is ready to be used on documents outside of the training set, predicting the relevant sectors of any document fed to it.

-

Production. The model is tuned and performing predictions with reasonable accuracy, and now it’s time to make it available to users. Using the development sector label example, this would likely mean creating a user interface—like a web page—to upload or point to documents to be labeled.

Learning from What’s at Hand

While applications are still in nascent stages, there is enormous potential going forward for machine learning in international development. A recent U.S. Agency for International Development guide on machine learning highlights its relevance to early warning systems, situational awareness applications, and algorithms to supplement development data gaps. The guide asserts that emerging machine learning applications “promise to reshape healthcare, agriculture, and democracy in the developing world.” More immediately, in a field well known for reinventing the wheel, machine learning approaches such as NLP can help stakeholders efficiently mine and coalesce knowledge gained over decades of research and practice.

Matt Styslinger is a Data Scientist at DAI.