Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Towards Inclusive Machine Translation: A Case for User-Centered Design in Machine Learning

Jan 28, 2021

In November 2020, Masakhane, a grassroots natural language process (NLP) community whose “mission is to strengthen and spur NLP in African languages, for Africans, by Africans,” published a paper titled “Participatory Research for Low-resourced Machine Translation: A Case Study in African Languages.” Machine translation refers to the use of software to translate digital and nondigital text and speech from one language into another. Google Translate is one of the more common examples of machine translation. Most of us have experienced issues translating text, especially sentences and phrases, as Google Translate often has difficulty detecting meaning and context. Due to these challenges, it can often give users incorrect word-for-word translations. (In your free time, search for the #GoogleTranslateFail hashtag on Twitter for a whole host of mistranslated content and a good laugh.)

Google Translate, and other mainstream machine translation tools, are also limited in the number of languages they are able to translate. As of today, Google Translate offers support for only 108 of the more than 7,000 languages spoken across the globe. Many of the languages that are not supported are what machine learning researchers consider to be “low-resourced,” a term used to describe languages that have few digital resources available and, more importantly, that are less commonly taught, endangered, or low density. The Masakhane paper outlines an alternative “participatory” approach for low-resourced languages to standard NLP tasks such as crowd-sourced annotation for training data and evaluation benchmarks. To learn more about the basics of NLP, head to our previous blog post on the importance of NLP in development.

Why the Need for an ‘Alternative’ Approach?

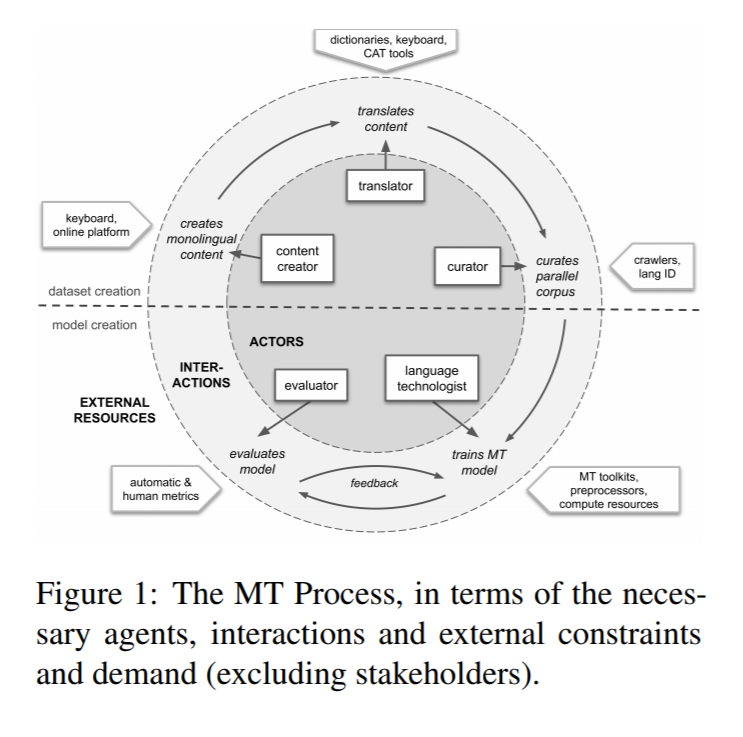

The authors outline a variety of roles that are necessary for an NLP task: stakeholders, content creators, translators, curators, language technologists, and evaluators. Each is responsible for a different task in the NLP pipeline, but all interact together to create machine translation datasets and models, as seen in the graphic below.

Source: Nekoto et al 2020

One of the major constraints to studying these languages is that there are few researchers who can speak the language they are studying. As a result, the machine translation process is often examined without knowledge of the country and cultural context and, therefore, unsuccessful.

Additional factors affecting the availability of resources for low-resourced languages include:

- Low demand from stakeholders: Described by the authors as a ‘chicken-or-egg’ scenario, low-resourced languages have limited demand for content creation and translation, which could improve if there was more content available in those languages. More content incentivizes stakeholder interest, but stakeholder interest leads to more content.

- Limited access to technology: Especially for digital content, technology infrastructure is necessary to be able to convert words from people’s brains into a computer. This includes access to technology, keyboards, and computing resources.

- Techniques developed in high-resourced societies might not apply due to computer, infrastructure, or time constraints: NLP tools built on top of English datasets and other languages commonly spoken in the Global North are often incompatible with low-resourced languages. Some of these differences include divergent grammar structures and word parts.

A Participatory Approach

With these issues in mind, the authors present a case study to illustrate the impact of a participatory approach to machine translation for low-resourced languages. They brought together individuals interested in NLP from across the African continent to develop datasets, benchmarks, and models for more than 30 African languages. The initiative brought together more than 400 participants from at least 20 different countries. There were no educational or professional barriers to participation, an acknowledgement that there are few machine learning researchers with higher education degrees on the African continent.

The authors hypothesized that this kind of approach would improve machine translation for low-resourced languages—and they were right. Participants created the first-ever evaluation benchmarks and training datasets for these 30 languages and published numerous research papers with these new resources. Additionally, more than 80 percent of participants noted that the initiative helped them find mentors or collaborators.

Implications for Development

Reading this blog, you might wonder what this has to do with development. Use of NLP has slowly increased in development projects over the years—our work in partnership with the Promote: Women in the Economy project in Afghanistan is an example of that—and I anticipate that this will only continue to grow. The outcomes of this research have longstanding implications for the use of NLP tools in international development, two of which are outlined below.

The communities that we partner with are multilingual and deserve access to the same tools and solutions that are currently available in English in their native language. We, as development professionals, cannot claim to be working to serve all communities if we are only working in languages that are more commonly used in the Global North. This is not to say that translation is currently not a component of our work—it is. However, a tool that facilitates knowledge and skill-sharing across more low-resourced languages (like the 1,500 to 2,000 languages currently in use on the African continent alone) provides greater opportunity for collaboration and communication.

Additionally, the participatory approach described in the paper speaks to one of the Principles for Digital Development—design with the user. The case study is a prime example of designing machine learning tools with the users. Many of the participants were native speakers of the languages that were being studied and are anticipated to be the ones who will continue to develop and use these resources. Artificial intelligence and machine learning have not historically designed with the user. Tasks like model building and dataset development are often outsourced to save time and efficiency. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform was set up for this exact reason; users are able to hire remote workers to crowdsource annotations for training data through the platform. Additionally, job descriptions for data scientists and machine learning researchers often require a Ph.D., an academic qualification not easily afforded to all. This limits the individuals who are allowed to participate in machine learning processes.

While we are not at a point where we can use machine translation for low-resourced languages in the way that we use Google Translate, this research offers new insight into how we can design machine learning tools with the user and hope that one day, translating English into Yoruba or Kikuyu will be as easy as translating English into French.

To read the full open-access paper, click here.