Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Machine Learning Changes the Business Case for Automated Phishing Attacks

Feb 21, 2019

Researchers have demonstrated the capability of machine learning to help with everything from saving honeybees and tracking flu vaccine uptake, to aiding in the fight against bioterrorism, and plenty in between.

But machine learning can also be put to less-scrupulous uses just as easily. Social engineering is a type of cyber attack that deceives users into creating security breaches, typically through emails and phone calls (often called ‘phishing’), and the marriage of machine learning with social engineering is poised to be a burgeoning issue in the near future. This issue is a global problem, but developing markets are often at the highest risk for cyberattacks due to the lack of capacity to defend against and track such attacks. As such, they often find themselves as the testing grounds for novel attack methods before they reach more developed markets.

While exact figures for developing markets can be hard to obtain for many of the same reasons they’re a tempting target, research suggests these attacks are surprisingly common. A security firm reported in its yearly phishing study that 83 percent of global respondents experienced phishing attacks in 2018, a 9 percent increase year over year. The impact of these incidents can be profound; another report on cybersecurity in Africa found that social engineering and phishing combined amounted to a $274 million loss across Africa in 2017, or 25 percent of total losses due to cyberattacks.

How Does Machine Learning Impact Social Engineering?

With more data available than ever before, significant progress has been made in teaching computers to understand and mimic human communication. While anyone who has tried to have a conversation with their Alexa or Google Home can attest to the fact that they aren’t exactly stimulating conversationalists, it’s hard to deny it’s getting more difficult to tell a computer from a human simply based on communication. A number of companies have been using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to analyze and generate marketing copy for email and social media ad campaigns, and these campaigns have been outperforming traditional tactics by fairly large margins.

At the moment, the only thing holding back social engineering attacks from more widespread deployment is the time it takes to execute them. By their very nature, these attacks require a human on the other end for any meaningful chance of success, and while initial phishing messages can often be automated and sent en masse, the careful, coaxing follow-up is typically with another human. This applies even more so for pretexting attacks, which are often similar to phishing but involve doing research upfront to identify potential weaknesses in a target’s communications.

Real-World Examples

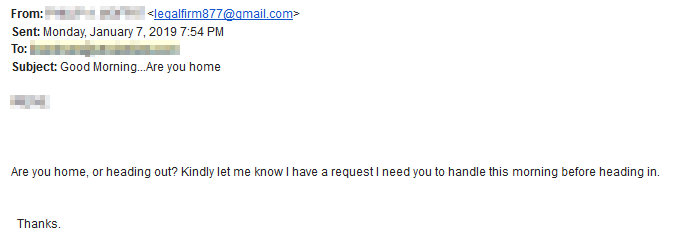

Recently, a number of organizations have been hit with a phishing attack that looks something like this:

Screenshot taken by Zach of a phishing attack.

This email was sent to all employees at a company, personally addressed to each, and listing the owner’s name as the sender. It doesn’t even feature email spoofing, the perpetrators simply used automatically generated Gmail addresses. On its face this is not a particularly sophisticated phishing attack; a seasoned user could come up with no less than eight reasons for why it should have been deleted. But personalization—using the business owner’s and employees’ names—is what makes it unique. Organizations were previously unlikely to be hit with a phishing attack of this nature since it requires collecting and inputting personal information and you were protected primarily by virtue of the number of targets available. The odds are quite low that malicious actors will choose to research and target you out of the millions listed online.

Fortunately, a more experienced employee at the company noticed that the owner’s name was not formatted the same as on his actual account. This fake email used all capital letters and included a middle initial, which is exactly how the owner’s name is listed on his website profile page.

As it turns out, these emails were automatically generated and sent out by a group that created a rudimentary machine learning program to skim company websites for employee profiles, specifically the kind that include contact information, and then logged that data to be used for sending out these personalized phishing attacks. It was even able to guess which of the profiles were most likely to prompt compliance and selected that name to be used as the fake sender.

What Can We Do?

The most important thing right now is to be aware. It’s not important to understand how the data is being gathered, but what’s important to know is that machine learning provides the capability to parse information listed on your website and link it together with information from your social networks, including your employees listed on LinkedIn, and utilize it to create phishing attacks with much higher rates of success.

It’s easy for security professionals to dismiss the seriousness of social engineering attacks given their typical lack of sophistication, but according to the Verizon 2018 Data Breach Investigation Report, 17 percent of all data breaches in 2017 were social attacks and of those 98 percent were phishing and pretexting attacks. This makes social engineering incidents the third most common type of data security breach.

With the introduction of machine learning, expect to see that number increase as more sophisticated methods are employed. At some point in the future we’ll see groups adopt the same capabilities already at use in corporate marketing campaigns to automatically research targets and use AI to generate initial emails from that data and create followup messages based on replies received.

As machine learning lowers the labor cost for more sophisticated phishing attacks, it might be time for organizations to re-think what they consider sensitive data, and when deploying digital tools to aid in international development, consideration must be given for vulnerabilities in both the software and human elements.

Zach Gieske is an information sciences and technology specialist who works as an independent consultant. He studied international politics and information sciences and technology at Penn State University Park. Zach ensures that clients follow modern data security best practices for all their technical applications and strives to ensure security and safety in the digital realm. In addition to his work as a consultant, Zach serves as an Operations Analyst for a Washington, D.C.-based trade association.