Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Location-Based Platform Work Presents Benefits—and Risks—to Workers in the Global South, Part 1

Nov 4, 2021

One of the wonders of the digital age is that if at 11 pm I suddenly crave a pizza (Hawaiian preferably—no shame!), all I have to do is click a few buttons on my phone, and voila! pizza is delivered to my door. While it may feel like the pizza arrived by magic, especially given the “no-contact” options made available since the start of COVID-19, the satisfaction of my late-night craving is made possible by the work of independent contractors hired by digital platforms such as Uber and DoorDash to deliver products in cities around the world.

As we continue to grapple with the pandemic, companies specializing in delivery services have seen their revenue rise exponentially. Uber saw its delivery bookings increase by 166 percent since the first quarter of 2020, primarily due to its food delivery services during the first several months of the pandemic. These services are also increasingly relevant across the Global South. With internet penetration and smartphone use growing in developing countries, digital platforms provide consumers and businesses, especially micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), with transportation and delivery services and become an opportunity for people to supplement lost income. According to the GSM Association, countries that saw a more significant hit to their informal economies in 2020 experienced a rise in employment via digital platforms.

As the anticipated “end” of the pandemic stretches further and further into the future (and with it, concerns about the return of the informal jobs that employed a majority of people in developing countries), the development sector seems to be expanding its analysis of the potential benefits and drawbacks of digital platform work. Organizations such as Caribou Digital, BFA Global, and the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) have already done some thinking on the potential impact platform work could have in the development context, and the results are… mixed.

Below, I review some of the benefits and what I find to be increasingly worrying risks of platform work, specifically location-based platform work such as taxi and food delivery services, in developing countries. As Claudia McKay and Gayatri Murthy of CGAP write, “platform work is neither good nor bad.” However, I believe understanding how it’s impacting workers in the developing world can help guide the degree to which we promote platform work in the digital development space as a reliable or decent employment option.

Photo: Unsplash.

Not All Platform Work is the Same

First, it is essential to note that there are several different types of work made available by digital platform companies. According to a segmentation developed by BFA Global, working for Uber, Lyft, or another such ride-hailing or delivery platform would count as location-based gig work. This differs from cloud work, which is web-based and not location-dependent (the International Labor Organization (ILO) refers to this as online web-based platform work). Though each is considered part of the “gig economy” that we have heard so much about over the last decade, there are some big differences in terms of the control that these workers have over their work. Location-based platform workers have their rides and rates assigned by the platform’s algorithm (think an Uber driver is receiving a notification to accept a new rider). In contrast, cloud or online web-based platform workers “negotiate their own work on an individual basis” (think a freelance graphic designer on Fiverr choosing which jobs they would like to do).

The fact that location-based workers do not control certain aspects of their work in the same way that other platform workers do has been one of the central themes in the ongoing legal battles in the United States and the United Kingdom over whether these ride-hailing and delivery workers should be considered independent contractors or employees. Those who advocate for classifying these workers as employees believe that truly independent contractors would have more power to negotiate pay and other terms of their working engagement. In this blog, I will primarily focus on the experiences of location-based platform workers as the ongoing discussion about their labor rights in the United States inspired my desire to understand how this dynamic is unfolding in the countries where DAI and other developing organizations work.

The Good

So let’s start with some of the pros of attaining work on a digital platform. (Note that these are quite general as these benefits may not hold true everywhere. These benefits will also not vary significantly between location- and cloud-based workers.)

-

Income Smoothing: One of the primary benefits of digital platform work in the developing world is its ability to help smooth incomes that may fluctuate greatly over time. As previously mentioned, the informal economy employs a majority of workers in most developing countries, meaning that these workers may or may not receive a regular, predictable salary. Finding ways to smooth income has become particularly critical given the economic disruption of the pandemic. In Nigeria, for example, 20 percent of workers lost their jobs due to COVID-19. Digital platform work promises that some of these workers could make ends meet by taking up ride-hailing or delivery jobs. Additionally, in some instances, these jobs can have higher hourly earnings than other types of work. According to a study conducted by the ILO, location-based workers, specifically taxi drivers and delivery workers, received higher hourly wages than other traditional sectors. However, the report states that these earnings are boosted by the bonuses platform companies make available to attract more drivers to their platforms.

-

Flexibility: This may go without saying; however, having the opportunity to create one’s own work schedule offers freedom to pursue multiple income-generating opportunities simultaneously. While this may seem like a blessing for the entrepreneurial-minded among us, it is a challenging necessity in some developing countries where workers, especially young people, migrants, and other vulnerable groups, face increasing difficulty securing formal, full-time, and salaried work. In particular, many youth populations are being forced to rely on “mixed livelihoods” to maintain economic stability. Digital platforms allow them to patch together different income-generating activities to sustain a stable income. The flexibility of this work is also desirable to women, who may not be able to pursue full-time employment outside of the home due to responsibilities such as child care. Despite this, we should note that women are still under-represented in the digital platform workforce, making up only one in 10 workers on location-based platforms.

-

Market Access: Broader market access is a massive benefit to workers who, through digital platforms, can drastically lower the level of effort needed to find new clients. As with Uber or similar platforms, the company’s algorithm is responsible for matching workers to users and setting the price for the service delivered. While this level of efficiency could be interpreted as making workers’ lives easier by taking out the guesswork of, for example, where to look for passengers, this could also be interpreted as taking away some of their agency (more on this in the next blog). MSMEs also benefit from greater market access, as they are able to rely on delivery drivers to expand the reach of their services. For example, restaurants have become quite reliant on delivery drivers to maintain operations during the pandemic as their food can now reach customers who may have never patronized the establishment otherwise.

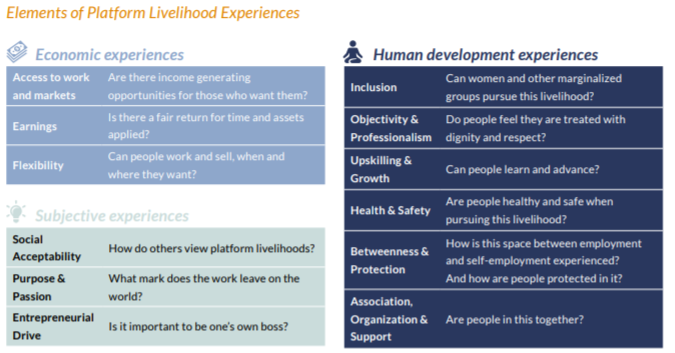

All the benefits that I have mentioned above are purely economic. However, as Caribou Digital highlights in its October 2020 report on the experience of platform livelihoods in the Global South, there are so many more considerations to make when determining whether the experience of working with a digital platform is fulfilling and decent. Recent studies such as the one highlighted in this article from Rest of the World show that platform workers don’t uniformly see benefits associated with human development experiences (see Caribou Digital’s framework below), such as health and safety or upskilling and growth.

Image: Caribou Digital

Coming Up: The Bad

In Part 2, we will discuss some of these challenges and risks associated with location-based work and implications for workers in developing countries. In the meantime, I highly recommend reading the ILO and Caribou Digital reports referenced here for a more detailed look into how digital platforms are shaping work and livelihoods in the Global South.