Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Frontier Insights South Sudan: Understanding Children's Digital Access

Oct 5, 2021

Throughout the summer, the DAI Center for Digital Acceleration has been working with Sesame Workshop to explore the possibilities for using digital tools to provide education services to young children in crisis-affected communities.

Using DAI’s Frontier Insights™ methodology, our researchers in Colombia, Yemen, and South Sudan talked to children and their parents and caregivers to understand communities’ barriers to connectivity and their technology usage habits. Through this research, we sought to understand how technology might be leveraged to improve access to educational video content. In this series, we share our findings and interesting insights into the digital lives of children in these contexts.

In August, our research team traveled to the Protection of Civilians (POC) camp in Juba, South Sudan, which has a population of more than 35,000 South Sudanese internally displaced persons (IDPs). The research team spent 10 days in Juba POC, interviewing 72 people including children, ages 3 to 8, and their parents and caregivers.

Key Findings

The principal challenges children in the POC face in accessing technology relate to electricity constraints and concerns their parents and caregivers have around mobile phone usage. There is a high level of caution around children’s use of technology and access to the internet: Parents and caregivers are not only concerned about possible damage to or loss of the device when used by children, but also with the physical safety of their children and the negative influence that using technology may have on them. However, despite the numerous connectivity and affordability constraints, families do use their mobile phones for entertainment: playing offline games they have purchased at the market and downloaded from their SD cards. In this blog, we detail some of these key findings.

1. Most interviewees have or access a mobile phone, but few have any internet access

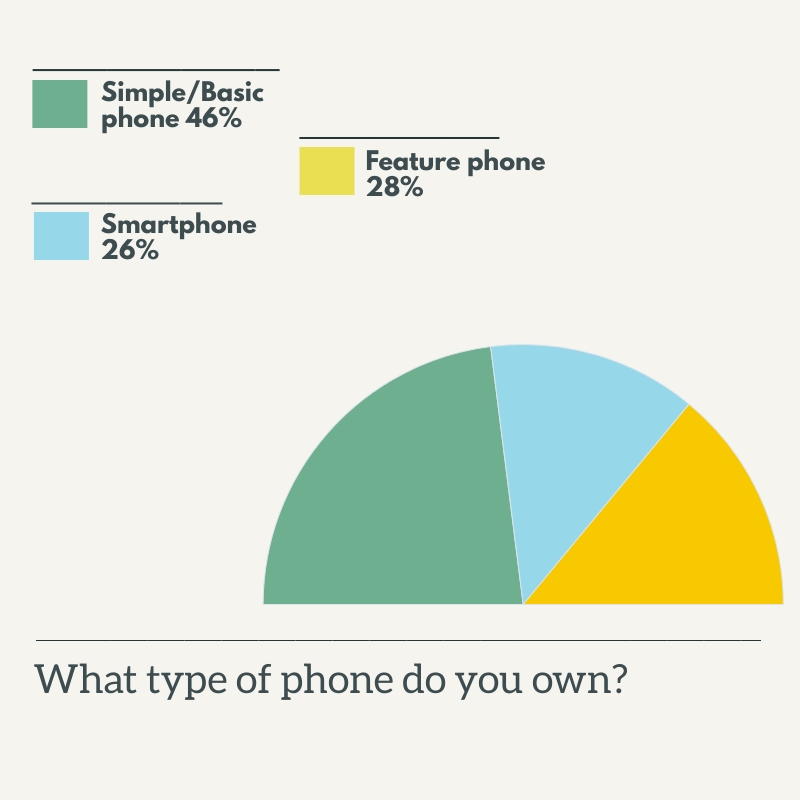

Of the 72 interviewees, 57 parents and caregivers own a mobile phone (79 percent). Men are much more likely to own a smartphone, but there is no evidence of gender disparity in ownership and access, as both women and men own mobile phones and most have multiple in their homes.

Of the 15 who do not own a mobile phone, 10 are able to use the mobile of someone else in or outside of their household and five families have no access at all. Interestingly, those without a mobile have a radio at home as their main source of entertainment.

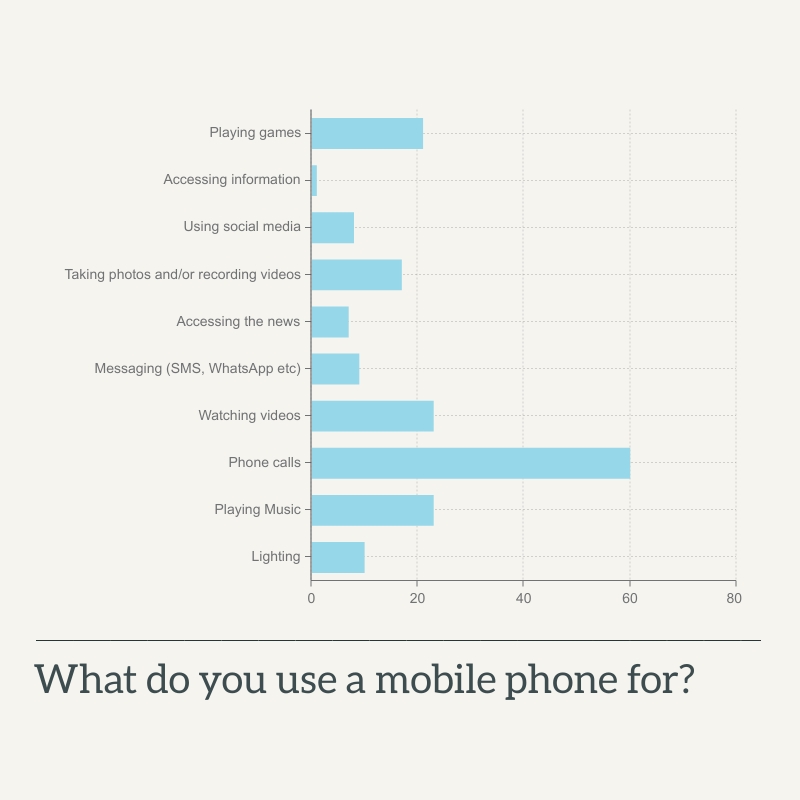

Aside from phone calls, interviewees mainly use their phones for entertainment, including watching videos, playing games, and listening to music. Many also report that due to a lack of electricity and lighting in their homes, they rely on their mobile phones for lighting at night.

Although more than half of respondents own a feature or smartphone, less than 30 percent access the internet, as the cost of data is too high.

2. Mobile data is the only way to access the internet

Mobile data is the only way to access the internet, as there are no community internet access sites (such as an internet café, community center, or school) in the camps. The camps do receive a 3G data signal through two mobile network operators, Zaine and MTN. Through a testing of Sesame Workshop videos on YouTube with a 3G connection, the enumerator found that the connection was sufficient to load the video within a minute and play video without stopping, rating it very watchable.

3. Electricity is a key barrier to technology access

The biggest barrier to technology access and use is electricity. Almost all—99 percent—of interviewees report not having electricity in their homes. To charge their phones, residents go to local markets with charging stations and pay a fee. Many limit how much they use their mobile phone to conserve battery life.

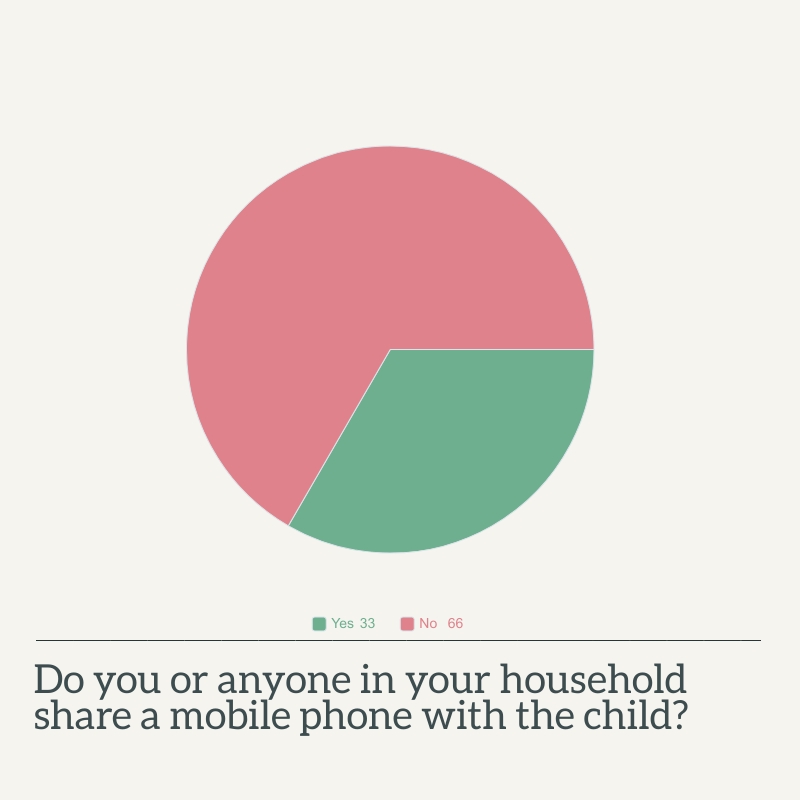

4. Parents are reluctant to share their phones with children, due to fears over theft and bad content

Aside from the conservation of electricity, the three main concerns are safety of the device and their child, damage to the phone, and negative influence on their child either through too much exposure to the mobile phone or the ability to access “bad videos.” Parents are also worried their child may damage the phone or accidentally delete information. As a result, parents only share their phones with children inside their homes, control what videos and games are put on the phone, and ensure that the child does not use the mobile phone unsupervised. Parents do not allow their children to access the internet, due to concerns over “bad” content and due to the high cost of data.

5. With no access to televisions, mobile phones are the way people view videos

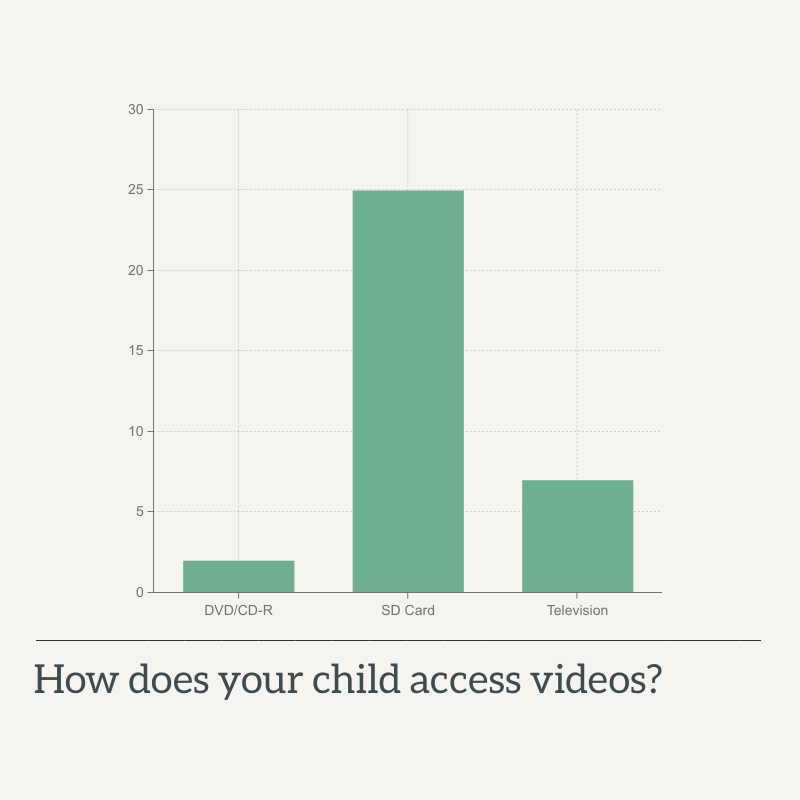

A vast majority of interviewees do not own a television in their homes nor watch television: only two families have a television at home, and only seven children have access to a television outside of their home at a neighbor’s house. There are “video halls” available outside of the POC site, more than 5 kilometers away. At these sites, children can watch cartoons on television, but in general, it is considered too dangerous to travel there.

The main way both adults and children access and watch videos in the camp is through videos uploaded to mobile phones. To get these videos, people go to small kiosks in the market area of the camp and have shop workers upload videos onto their SD cards. The most watched videos for children were music videos from a Tanzanian artist called Diamond Platinum and “Tom and Jerry” cartoons, the “Wizard of Oz,” and a Nigerian children’s television program called “The Baby Police.” People are able to buy a variety of television series and movies from China, Indonesia, India, and Nigeria all at a cost of 250-500 SSP ($0.56-$1.12).

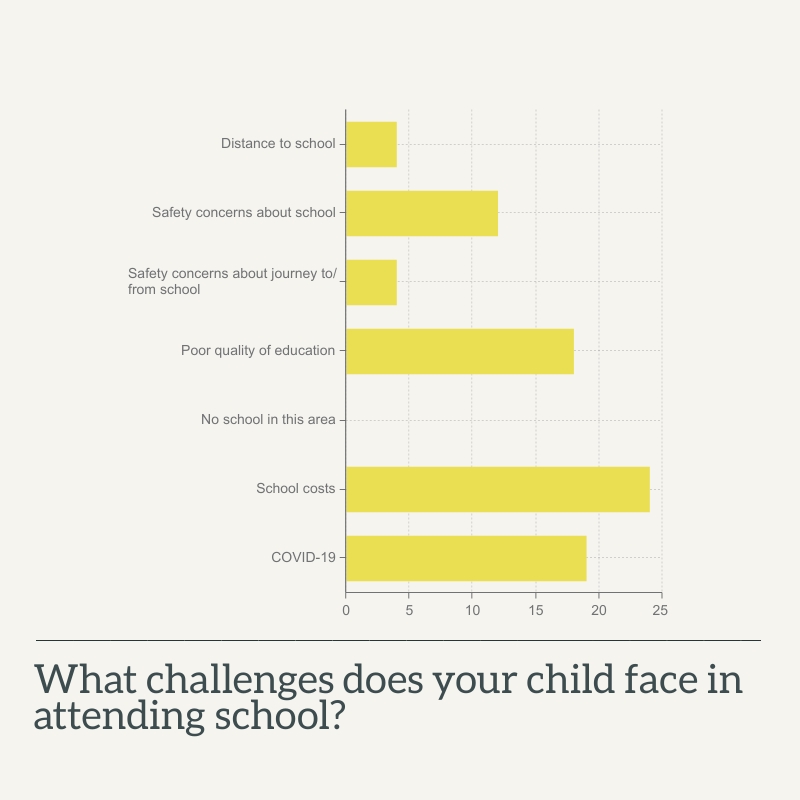

6. Children are enrolled in school, but face numerous challenges to attend

More than 80 percent of children are enrolled in classroom-based education which is provided by nongovernmental organizations and churches in the POC. The biggest challenge to accessing formal education is affordability: costs such as uniforms, textbooks, and stationery are too high, preventing some parents from sending their children to school.

Parents and caregivers also expressed concern about the quality of education. They noted that there are not enough schools to serve the population, leading to overcrowding that poses a safety risk to younger children who are in classes with older children. For many, the schools are very far away, meaning children must walk there, often alone. A lack of toilets also means children have to use nearby bushes, which is unsafe. The situation is reported to have worsened since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, as children have not been able to attend school as regularly.

What Next?

Understanding the barriers and opportunities to access technology, connectivity, and virtual learning and videos in South Sudan and the two other focus countries (Colombia and Yemen) will guide how Sesame Workshop determines the best technology solution for a given context. The next phase of this project will take these findings and develop a framework to guide the decision-making process and lead to the appropriate choices in technology solutions, methodologies, and partnerships to distribute this content blocks in crisis-affected communities.

Sesame Workshop’s Play to Learn is an innovative humanitarian program from Sesame Workshop, BRAC, the International Rescue Committee, NYU Global TIES for Children, and the LEGO Foundation that harnesses the power of play to deliver critical early learning to children affected by the Rohingya and Syrian refugee crises. Through a combination of educational media and direct services, Play to Learn reaches families in their homes, health centers, play spaces, and via mobile phones—providing the tools needed to promote nurturing care and help children learn and thrive. In collaboration with independent evaluator NYU Global TIES for Children, we are measuring the program’s impact on children’s development and caregivers’ mental health and well-being. By sharing what we learn and advocating for increased prioritization and investment in early childhood interventions in crisis contexts, we are laying the foundation to transform how the world supports children affected by crisis, wherever they may be.

Thank you to our lead researcher Moi Moris Gabriel and his team of enumerators for conducting this research.