Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Frontier Insights Colombia: Understanding Children’s Digital Access

Sep 30, 2021

Throughout the summer, DAI’s Center for Digital Acceleration has been working with the Sesame Workshop exploring the use of digital education tools for young children in crisis-affected communities.

Using DAI’s Frontier Insights™ methodology, our researchers in Colombia, South Sudan, and Yemen spoke with children and their parents and caregivers to understand their communities’ barriers to connectivity and tech habits. Through this research, we sought to understand how technology might be leveraged to improve access to educational content. In this series, we share our insights into the digital lives of children in these countries.

In Colombia, our research team interviewed 68 Venezuelan refugee and migrant families, including children, aged 3 to 8, and their parents and caregivers. The research took place in Bogotá—home to approximately 350,000 Venezuelan refugees—and Cúcuta—a key border town on the Colombia-Venezuela Border with the highest percentage of migrants and refugees in the country—as well as two cities in La Guajira, Maicao, and Riohacha, along the northern part of the Colombia-Venezuela border. In Maicao, there is an informal quasi-refugee camp named La Pista, made of plastic tent shelters with approximately 200 Venezuelan refugee families living in poor conditions.

Key Findings

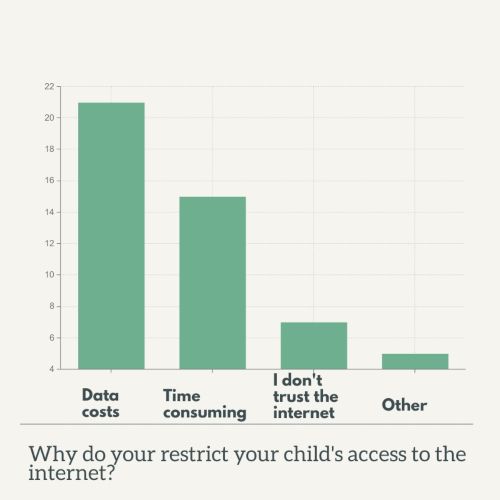

Access to mobile devices and the internet is high across the three locations, but the high cost of mobile data is the most significant barrier to children’s access to the internet and clearly affects the way children participate in formal education and informal learning and entertainment. Refugee children in all locations in Colombia are already heavy users of online video content, supported by their parents who encourage access to educational materials. We discovered that:

1. A majority of families access the internet through mobile data, but costs are prohibitively high

More than 90 percent of interviewees access the internet via mobile data on their or a family member’s mobile phone and all but two children access the internet. Interviewees say that public wifi or community internet access points are generally not available. The biggest challenge these families have in accessing the internet is cost. Purchasing data packages depends fully on whether they have extra money after paying for their basic needs (i.e. food, housing, etc.), and only then do they buy data: data is considered a luxury that families may go for weeks without.

In general, interviewees do not consider connectivity or internet quality a barrier to internet access, rating the quality of data connectivity as 8 out of 10 or higher.

2. Mothers share their mobile phones with their children, but limit amount due to cost and phone sharing

All families have at least one mobile phone per household, which may be shared between household members: in 87 percent of cases the mobile phone is shared with the children. Almost all of the people we spoke with have a smartphone at home.

Some interviewees note that their families got their first mobile phone due to the COVID-19 pandemic so that their children could keep up with schoolwork after school became virtual. More than 90 percent of mothers share their mobile phone with their children daily, with the remaining mothers share their phones at least once per week.

Interviewees note that the internet is a powerful tool for education, but they limit the amount their child uses it, sometimes to punish them for bad behavior, or because they do not wish for their child to be on the phone all the time, particularly where they are not using it for education. Others worry about damage to the device.

3. Parents are concerned about online content

The surveys found 57 percent of parents are concerned about the safety and security of their children when using mobile phones and computers, particularly in terms of possible access to pornography or violent content. The only physical safety concerns raised were in the community of La Pista, where theft of phones, especially targeting women and girls, is an issue. Despite these concerns, parents don’t tend to limit their child’s access.

.jpeg)

Focus Group Discussion,Cúcuta.

4. Most children do not have a TV but use phones for video content

More than two-thirds of families do not own a functioning TV. Families that have a TV in the house with or without cable or streaming services use it during the day for the children to watch children’s programs, though there are not many children’s programs on national channels. Six interviewees note that they watch television outside of the home, at the homes of other family members. In the La Pista settlement, there is a community access point, where the nonprofit Save the Children provides some educational support including screening movies for children.

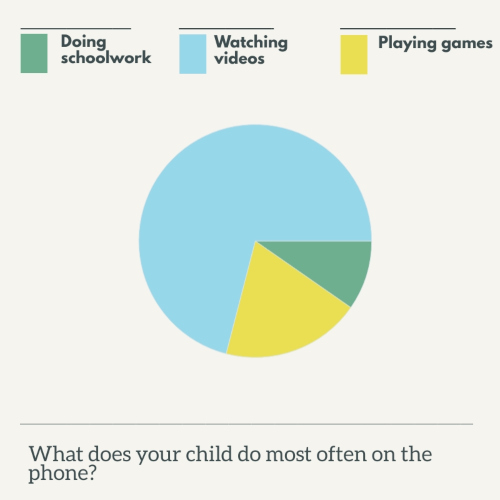

Almost all of the children report using a mobile phone to watch videos, and some (eight children) use it for schoolwork. Sixteen interviewees note that children also sometimes play games on the phone, as this does not require data. Only one or two children use the phone to take photos and record videos, use social media, and send text and WhatsApp messages. When the child and parents were asked what the child does most on the phone, watching videos came out on top (71 percent).

5. Social media is the internet and is even used for informal education

Both mothers and children note that Facebook is one of the primary sources of information for the families and the principal way in which they use the internet.

During the pandemic, some parents found informal ways to supplement their children’s education through other content, such as the videos on Facebook and YouTube. Interviewees use Facebook more often than other video platforms (76 percent watch videos on Facebook) such as YouTube because Facebook uses much less data. Data packages tend to offer free WhatsApp and Facebook as long as there is money left on their plan. Families therefore leave a small amount of money on the plan at all times, to ensure that they have access to these apps. Parents and children tend to use the search bar once to find things like alphabet videos, then rely on the algorithm to make suggestions on what to watch next.

Children are digitally savvy: When asked, all the children were able to identify Facebook, WhatsApp, and YouTube. Most children interviewed were able to open, search for and play a video on YouTube and Facebook, using the keyboard or voice commands. Children report that they like to watch cartoons such as Peppa Pig, Paw Patrol, Santiago de los Mares, La Princesa Sofia, and Barbie.

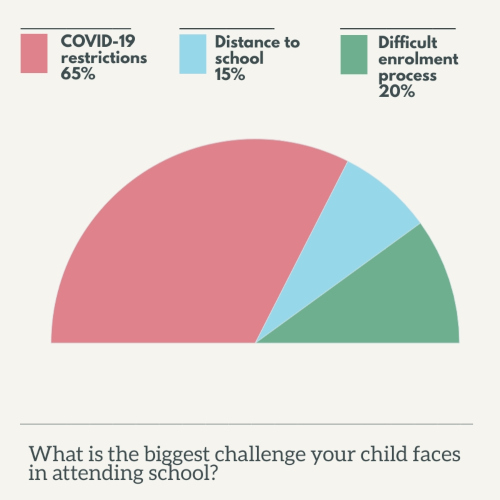

6. Most children are not enrolled in school due to COVID-19 or the complex enrollment process

Interviewees report COVID-19 restrictions to be one of the biggest obstacles to their children accessing education, including the fact that learning is so closely linked to access to the internet.

Those who bought phones during the pandemic did so to enable their children to access virtual learning through the formal system. Those children who are enrolled in school continue in a virtual format, where teachers send guides via WhatsApp with activities and questions about the subjects.

Mothers note that the lack of clarity in the documentation and processes for enrolling Venezuelan children in the Colombian education system has been a significant barrier to accessing education for this population: without parents having an education and a stable job, they will struggle to pay school fees. The enrolment process is also unclear; they struggle to understand which documents are needed to register their children. In Bogotá, mothers associate these challenges with xenophobia.

What Next?

Understanding the barriers and opportunities to accessing technology, connectivity, and virtual learning and videos in Colombia and the two other focus countries (South Sudan and Yemen) will guide how Sesame Workshop determines the best technology solution for a given context. The next phase of this project will take these findings and develop a framework to guide the decision-making process and lead to the appropriate choices in technology solutions, methodologies, and partnerships to distribute this content blocks in crisis-affected communities.

Sesame Workshop’s Play to Learn is an innovative humanitarian program from Sesame Workshop, BRAC, the International Rescue Committee, NYU Global TIES for Children, and the LEGO Foundation that harnesses the power of play to deliver critical early learning to children affected by the Rohingya and Syrian refugee crises. Through a combination of educational media and direct services, Play to Learn reaches families in their homes, health centers, play spaces, and via mobile phones—providing the tools needed to promote nurturing care and help children learn and thrive. In collaboration with independent evaluator NYU Global TIES for Children, we are measuring the program’s impact on children’s development and caregivers’ mental health and well-being. By sharing what we learn and advocating for increased prioritization and investment in early childhood interventions in crisis contexts, we are laying the foundation to transform how the world supports children affected by crisis, wherever they may be.

Thank you to our lead researcher Mariángela Villamil Cancino for conducting this research and to the nongovernmental organizations that supported her (Fundación Juntos Se Puede, Asociación Santo Ángel, and Fundación Nueva Ilusión).