Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Digital Insights Malawi: Information and Communication in Rural Communities

May 2, 2018

Last month, I spent two weeks in Malawi trying to gain a real understanding of technology use and media consumption habits of people in rural and marginalised communities. Along with a team of enumerators, I spoke to 183 women, men, girls and boys (ages 14 to 80) in different traditional authorities (TAs) in Northern, Central and Southern Malawi.

Alice talking tech in Mponda, Mangochi, Southern Malawi.

The process mirrored our Digital Insights work in other countries: using DAI’s Digital Insights methodology, we talked to people about how they receive information and what they trust the most; how they prefer to communicate; and when and why these use these tools. Here I outline some key findings concerning digital access and inclusion in these rural areas, but first, the numbers.

Key Findings

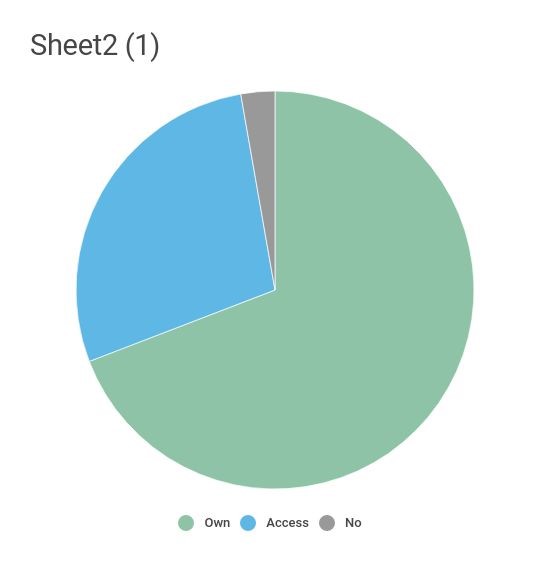

1. Mobile phone penetration is high, but the average isn’t representative

A lot of country-level data takes an average of mobile phone penetration, but this just isn’t representative or useful when designing targeted interventions. On average, just under 70 percent of those we interviewed have mobile phones, which may strike you as a high penetration for rural Malawi. However, once we drilled down our data by district, we found that the areas we visited in northern Malawi had a far lower penetration, at around 40 percent, compared to more than 80 percent in central and southern Malawi. The disparity went the same way for type of phone ownership: In the northern district, less than 15 percent of people had a feature or smart phone, compared to nearly 50 percent in the other locations.

Interestingly, in all districts mobile phones were widely shared among communities—between friends, family, and neighbours. Whether they owned the phone and shared it with anyone who needed it, shared ownership with a family member, or used their husband’s phone from time to time, 96 percent had some sort of regular access.

Those who did not have a phone or shared a friend’s cited expense of the airtime and data as a major barrier. Digital literacy was also a concern, particularly for the older generation.

Omega conducting an interview in Nankumba, Mangochi

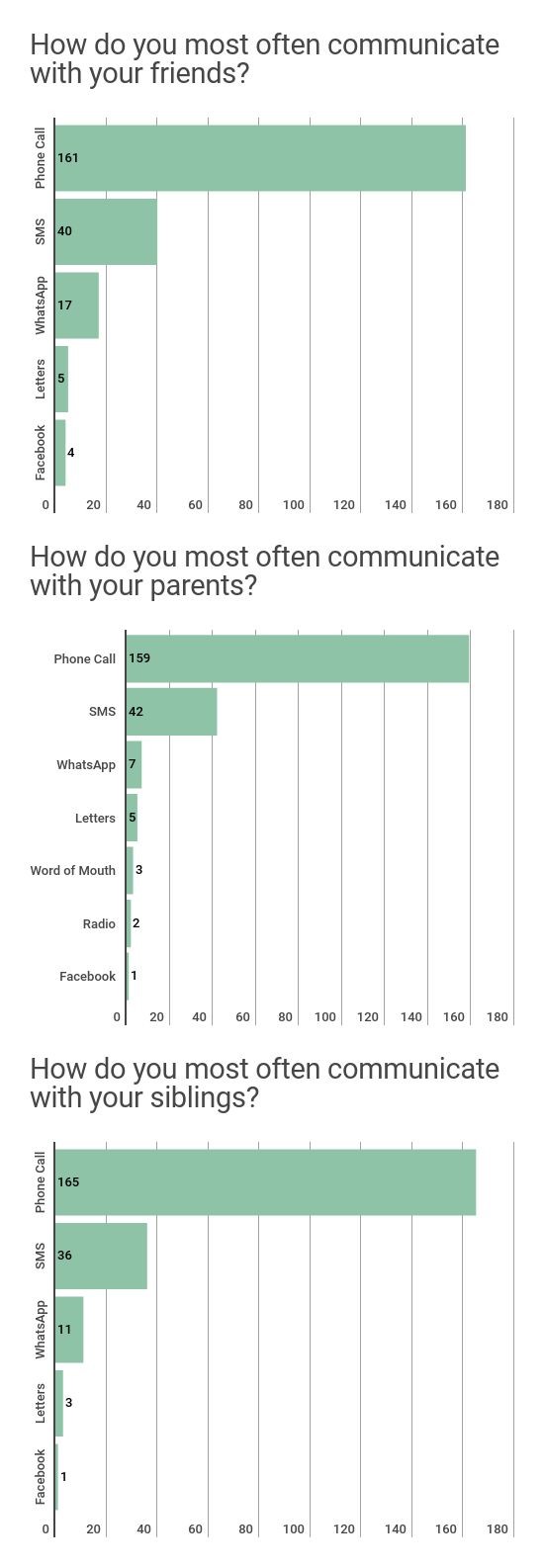

Perhaps it is therefore unsurprising that mobile phones are a vital tool of communication for most people: many choosing the speed and quick return of making a phone call. What is most interesting is that a clear majority use their phone only late evening and during the night, as this is when the discount bundles are available and service reportedly the strongest.

For most, text messaging is a last resort or a way of requesting a call-back, with many not trusting that the message will get there or concerned that the message remains on a person’s phone. Even those who do text are not avid users—a vast majority send just one or two per day, mostly call-back requests.

2. Very “social” media

The least used forms of communication are internet-based apps, even in districts where internet-enabled phones are owned by nearly 50 percent of people. Among the reasons behind the low uptake are the cost of data and digital illiteracy: A few older people remarked that they do not know how to use the internet-enabled features of their phones and instead rely on younger relatives.

Facebook was only mentioned by two people, both of whom were young men who use it as an information source but are not prolific users. Access to the internet is purely mobile: No one we spoke with uses social media or the internet in an internet cafe, at school, or at work.

Of the handful who use mobile data, all have WhatsApp. Most are under 30 and use the app in a social setting, sitting down with their friends after school, or to chat with other groups. Interestingly, a lot of people noted their own lack of WhatsApp, saying they could not afford the data or did not have an internet-enabled phone. They mentioned they use WhatsApp on a friend or relative’s phone when they need to message someone abroad or find some information. WhatsApp is clearly a social tool; and one that younger people feel they are missing out on.

Chindi, Mzimba, Northern Malawi

3. Digital gender divide in action

The disparity of phone ownership between males and females was most stark in northern and central Malawi: If we take the average of the three districts, the gender gap was at just under 40 percent. Mobile phone sharing is where the gender digital divide comes into the most light: Of the women and girls who do not own a phone, most report that they do not control when they use it; many share with their husband, father, or mother-in-law. Men and boys, on the other hand, tend to share with other male relatives in a more equal agreement. Young women and girls are the most likely group to have no access at all.

This social control is also reflected in the choice of radio programming. In Mchinji, central Malawi, control over a female’s use of a mobile or choice of radio programming is much higher than in the other areas—many reporting that their male relatives chose what is listened to. Whereas in Mzimba in the north, where many women attend radio listening clubs, choice of what the group listens to is made jointly.

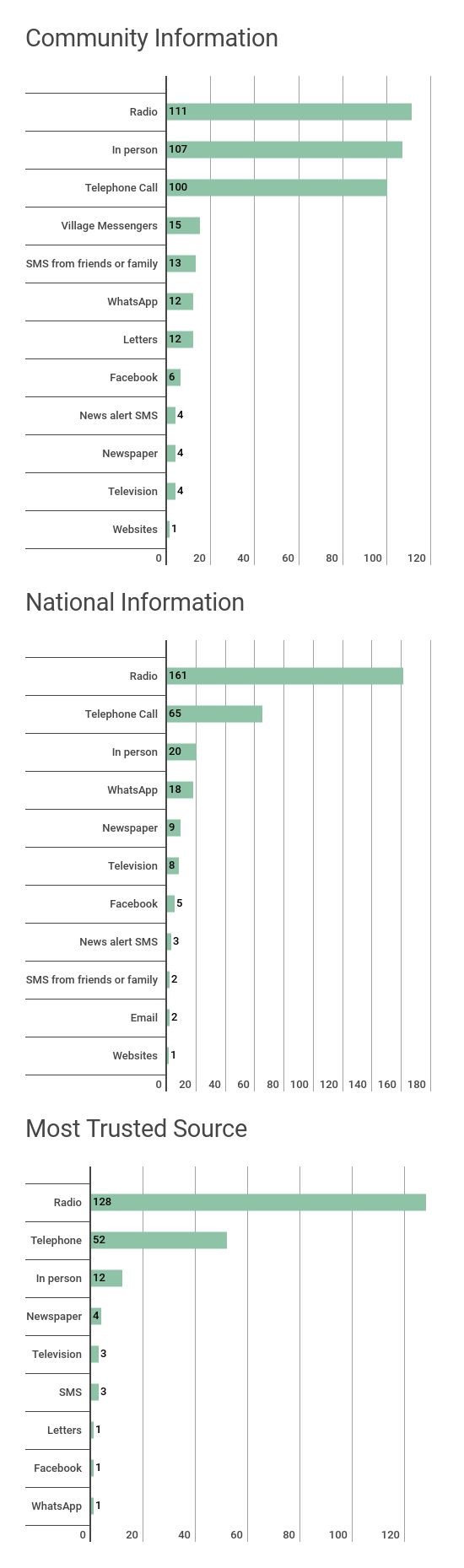

4. Radio is the star of the show

For receiving news and information, the real star of the show is radio. When asked how they like to receive information about both national and local goings on, and more informative topics such as their human rights, a clear majority said via radio. This is the only media source that is at all popular, with the main source of information otherwise being through people they are already in touch with by phone, in person, or through WhatsApp. In general, people trust the radio because it shares differing opinions; they feel the journalists have professional integrity; and that the information has been fact checked.

Conclusion

There is real evidence of some of the issues of digital access and inclusion that we so often talk about: social control of women and girls’ technology use; poor signal; digital illiteracy; the high cost of mobile phone data and airtime. Despite this, most people rely on their phones for communication and are just careful when and how much they use it. Old-school methods are still pertinent, with village messengers, letters, and the Chief still being a vital source of information. The WhatsApp craze among the younger generation and commitment to buying data no matter what the cost could see the dynamics change in the coming years, so I’d be keen to come back in a few years’ time.

A special thank you to Alice Kaunda (former Knowledge Management and Communications Manager, Tilitonse Fund) and all of the enumerators for their help.