Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Counting People is Hard: Biometrics can Help

Nov 8, 2016

This is a guest post written by Ben Mann, a development specialist at DAI with a wide range of interests. He is a policy wonk; water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) technical expert; ICT enthusiast; and general advocate for improved use of data and visualizations. Follow Ben on twitter @bhmann

One of the core functions of an effective monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system is the ability to accurately count things. Depending on your M&E strategy, you may be counting the number of schools built in a district, number of boreholes functioning in a region, or the number of microloans given to farmers in a cluster of villages. From my experience designing and operationalizing M&E plans for a range of private and bilaterally funded programs, counting people is by far the hardest and most complex to do—especially when you are trying to observe and record information on the same people over an extended time.

Counting people can be an easy task, if you have a highly controlled setting with a small set of people to count. Imagine you are a teacher in a classroom setting, teaching a night course to twenty students. The students paid $100 each for the course and applied online for the class that will meet once a week for eight weeks. Tracking attendance is almost a mindless activity. Simple visual observations can let you know if any students are missing on a given evening and you can record attendance in less than a minute.

This simple scenario can become dramatically more complex as we remove elements of control away from the teacher (or whomever is responsible for collecting data). What if instead of 20, pre-registered and documented students we open the course to anyone in 25-kilometer radius of the school? The course is also now free and pre-registration is not required. On any given week, the class has 15 to 100 participants. Unless you have an eidetic memory and super-hero level M&E skills, visual observations and an attendance sheet are no longer the best option.

Real Challenges to Tracking Beneficiaries

We encounter this issue frequently in our development projects. We often need to track our interventions per beneficiary over time, from a few weeks to multiple years. The reasons why this remains a challenging task are many. Our interventions are often targeting the “bottom of the pyramid,” disenfranchised populations that can be poorly educated or completely illiterate. Western schema for unique identifiers, such as names, become increasingly complicated when beneficiaries don’t know the difference between “given,” “first,” “last,” “family,” “surname,” or other descriptors that appear on a typical training attendance sheet. Inconsistent name spelling or frequency of common names wreak havoc to our data sets. There are dozens of ways to spell Jean Pierre in Haitian Creole, and chances are any given JP will spell it slightly differently from week to week. Government issued identification cards, another common tool used in the West for registering people, can be difficult to find in rural settings. Land tenure issues make registration by household address inconsistent and while I may have the same mobile phone number for over a decade, chances are your training attendee in Ghana has three different numbers in regular use that are less than a month old.

Enter ICT

This is one of the most promising areas for technology to fix a problem that we’ve failed to solve through analog means. We now have technology that can utilize machine-learning principles and biometrics to easily record a unique identifier for every beneficiary we encounter while minimizing the risk of double counting. Through our projects and partners, two innovative approaches are proving to provide time-saving, reliable, and cost-effective ways to track activity participants:

ICT Solution #1: Facial Recognition In Cambodia, SeeSaw is using Android phones and a simple server-side facial recognition software to track beneficiaries in a payment-by-results program. Utilizing built-in camera technology and a simple mobile survey form, each participant is recorded in seconds. After the surveys are submitted to the cloud-database, the facial recognition software uses each photo to determine if the participant matches an existing entry in the database and will catch anyone who may try to “double register.”

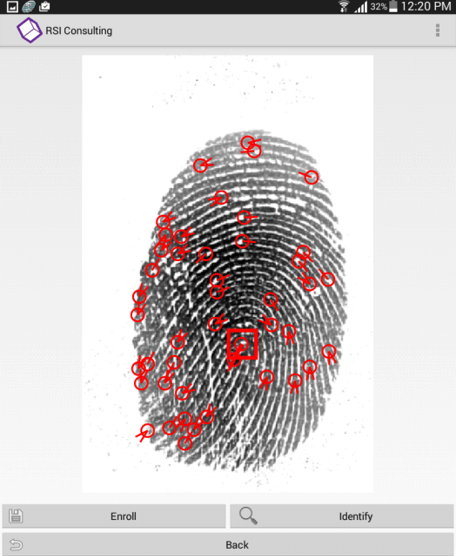

ICT Solution #2: Finger Print Scanning On our Promote Women In the Economy (WIE) program in Afghanistan, > RSI Consulting is capturing unique identifiers for project beneficiaries through finger print scanners. As part of their holistic M&E system, RSI is integrating thumbprint scanning technology into digital surveys. Whenever a beneficiary takes part in a new activity, they scan a thumbprint and are automatically logged as a new or continuing participant in the program.

Development partners aren’t the only ones utilizing biometrics for capturing information on beneficiaries or constituents. India’s AADHAAR program has registered more than 750 million voluntary participants since 2009 through both iris and fingerprint scanning as an alternative to traditional government issued identification cards. Technology firms have also recognized the benefits of capturing biometrics for identification, including the launch of Iris Recognition Technology on the Samsung Galaxy Tab or Apple’s Touch ID.

Security is Key

There are security concerns in using biometrics for individual identification. Growing concerns over government or private companies gaining access to personal information or biometric scans should not be dismissed. Addressing these security concerns with beneficiaries and discussing risks with biometrics should be included in any data collection plan or institutional review board. Like all personal data collected for M&E purposes, encryption and data-security measures need to be in place to protect project beneficiaries. Unique identifiers—whether names, photos, or biometric scans, should be wiped before any data is made open or public.