Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

Bangalore and the Hidden Costs of ‘Silicon Cities’

Sep 23, 2021

Over the last 25 years, Bangalore, India, has transformed itself from a relatively sleepy second-tier city into a regional anchor for global technology corporations and a hub for innovative technology-driven startups. The international development community has cheered the growth of similar hubs in low- and middle-income countries—think Nairobi’s Silicon Savannah or Lagos. But Bangalore’s story often obscures the massive environmental and social toll that rapid, tech-driven growth can have on a city.

I spent my formative years in Bangalore, from 1993 to 2005, when I moved to the United States. Since the mid-90s, Bangalore’s strong network of higher education institutions in the fields of engineering, business management, and sciences has fed a generation’s-worth of demand for young talent, and the city has grown apace. In a recent study, Bangalore beat London, Munich, Paris, and Berlin as the fastest-growing tech ecosystem in the world, increasing technology-based investment in the city from $1.3 billion in 2016 to $7.2 billion in 2020. Compare that to similar growth in the tech sector in Mumbai (India’s long-standing financial and business hub), which only grew from $0.7 billion to $1.2 billion in the same period. Bangalore also comes in sixth after Beijing, San Francisco, New York, Shanghai, and London in terms of venture capital investment.

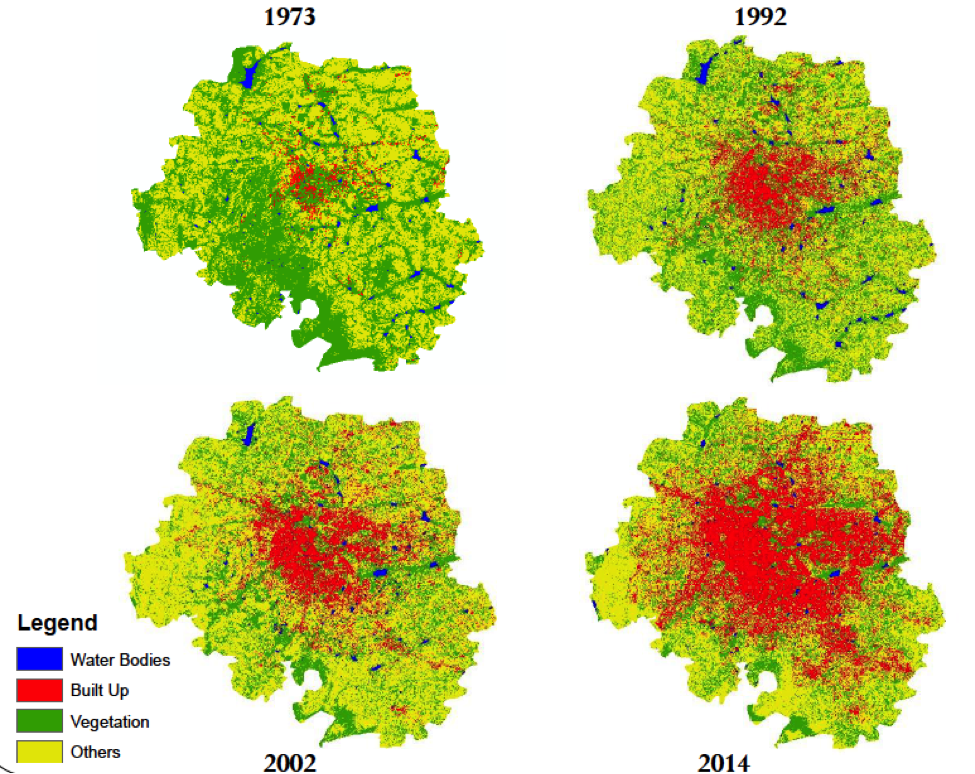

Graphic: Hungry Cities Partnership.

But this impressive growth trajectory is only part of the story. As CNN reported a couple of years ago, “India’s tech cities are choking on their success”. Bangalore’s population ballooned from 6.5 million in 2001 to almost 13 million in 2021. Its infrastructure has been strained beyond limit, and its gridlocked traffic is legendary, even by Indian standards. The city once known as the Garden City of India, famous for its urban parks and cool, tree-lined streets, has given way to a dense, warm, concrete sprawl that stretches out into the rural farmland surrounding the city. The city is also short of water. Recent research from the University of Minnesota shows how the booming tech industry has worsened socioeconomic inequality in the city.

It would, of course, be impossible to lay all of these issues at the feet of Bangalore’s technology industry. However, it is clear that the city was not prepared for the growth that the industry would create. The city’s roads, water systems, and other services were built to serve a much smaller population, and the city was unable to pivot to meet the needs that came with its transition from a sleepy vacation town to a digital hub.

To be sure, these are in part the lamentations of a long-absent immigrant, reminiscing about the good ol’ days of his hometown. But these are also warning signs that other technology centers in developing countries—Nairobi, Lagos, and others—should heed. Silicon Valley has given us many myths, many of which we’re interrogating today. But one of its more persistent myths is the unalloyed benefits of tech-driven economic growth. As always, the truth is much more complex. The international development community has a role to play here: In addition to the investments we are making in developing these cities’ technology sectors, we should also be making parallel investments in infrastructure, governance, climate resilience, and human capital that these cities will need to become thriving technology centers that aren’t victims of their own success.