Let us know what type of content you'd like to see more of. Fill out our three question survey.

What Are Algorithms and How Are They Biased?

Jul 23, 2020

In the age of Big Tech and social media, the term algorithm gets thrown around a lot to describe the unseen mechanism that determines what people see on social media or the suggestions that they receive on Netflix. But what exactly is an algorithm? And can an algorithm be biased?

Algorithms are simple. By definition, an algorithm is a set of rules used to achieve a specific objective. These rules can be implemented in many different ways—not only by computers, which is a common misconception. Let’s take a non-computer example: waking up and getting ready for work. For me, that means going through a routine to fully get going every day. As part of that routine, there are several things that I must do to feel awake. They are:

- Wake up.

- Take a shower.

- Drink some coffee.

These three steps, and the order in which I do them, are an algorithm.

When you Google search "algorithm" these are some of the images that come up, furthering the common misconception that algorithms are difficult to understand.

Using this definition, let’s explore whether an algorithm can be biased. What do I mean by algorithmic bias? This term refers to errors that appear in algorithms that lead to unfair outcomes.

To understand what algorithmic bias looks like in practice, think of the example I described above—the steps I take to fully wake up. If I asked three other people what steps they take to get ready in the morning, their answers would likely be a little bit different than mine and each other’s. The figure below shows three example responses:

The first person takes the following steps to fully wake up:

- Wakes up.

- Exercises.

- Takes a shower.

- Drinks coffee.

The second person takes the following steps to fully wake up:

- Wakes up.

- Drinks coffee.

- Brushes their teeth.

- Eats breakfast.

The third person takes the following steps to fully wake up:

- Wakes up.

- Brushes their teeth.

- Drinks coffee.

- Eats breakfast.

In other words, each individual has a unique series of actions. What if I created a set of rules (an algorithm) to explain or predict the steps that every person in the entire world takes to get ready in the morning based on these three people? My algorithm would be a very bad one, because it would fail to account for people who do not drink coffee or others who have different routines.

This example is a vast oversimplification of algorithmic bias, but it shows how each individual perspective and life experience influences the rules or steps a person takes to complete the same task or achieve the same objective.

The rules an algorithm follows matter a lot more when the stakes are higher. Algorithmic bias shows up everywhere, from search engines to hiring practices to healthcare delivery.

For example, there are a number of mobile applications that help to detect skin cancer by analyzing a picture of a mole or discoloration on a person’s skin and then predicting whether that mole or discoloration could be cancerous. These useful tools can help to pre-screen patients before they are referred to skin cancer specialists. However, multiple studies found that these applications are more accurate at detecting skin cancer on people with white skin versus those with black or brown skin. If medical professionals relied solely on this tool to determine who should seek further treatment, some people with black or brown skin would likely be misdiagnosed.

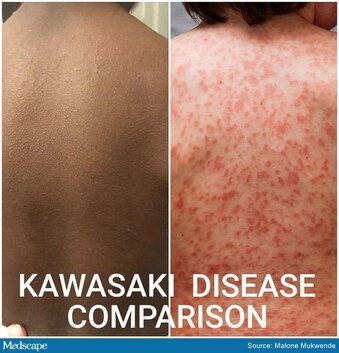

Efforts to address this type of bias are ongoing. Malone Mukwende, a second-year medical student at St. George’s in London, created a booklet on clinical care guidelines for people with black and brown skin. His goal was to raise awareness about how symptoms of certain diseases present differently on darker skin, something that had not been addressed in his formal medical education.

An image of how Kawasaki disease, a potential side effect of COVID-19 in children, manifests itself differently on lighter and darker skin.

As technology continues to become an integral part of people’s lives, the use of advanced algorithms in healthcare and the international development space will expand. However, for these tools to be effective, we must learn from past mistakes by rectifying and accounting for algorithmic bias to avoid excluding individuals or groups. Applications of algorithms on a mass scale, through AI and machine learning techniques, are still relatively nascent in many parts of the world. It is important that development professionals who work in these countries imbue these lessons into the tools they design or promote.

What can we do? Here are some suggestions to mitigate algorithmic bias:

- Diversify staff. Algorithms are only as inclusive the teams that create them. The lack of people of color, especially Black people, in technology and in development becomes apparent in the biased algorithms that these industries often use.

- Use appropriate data and information to create your algorithms. Bad data leads to bad algorithms. We cannot create algorithms with a small subset of the population and expect it to work for the general population. In a similar vein, we cannot simply export a solution that has been developed in the Global North and expect it to work in the Global South.

- Question whether automation is necessary. Algorithms that are executed by a computer are much more rigid than algorithms executed by a human being. As humans, we are able to make split-second decisions—decisions that in healthcare settings can save lives—which computers are unable to do. Consider if it is necessary to automate an algorithm—in many cases, it is neither necessary nor appropriate.

- Raise your individual awareness of algorithms. This suggestion goes beyond development and health. Big tech companies like Facebook and Google are using algorithms every day to control what we see and what we don’t see. Take a closer look—try to identify what algorithms are operating around you and how they might be biased.

Interested in learning more? Here are some additional resources in addition to those listed on our previous post:

- Algorithms of Oppression by Dr. Safiya Noble

- Automating Inequality by Virginia Eubanks

- Data Feminism by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein