Five Trends in Hardware to Watch

Jan 23, 2020

With the fast pace of technological change, it can be difficult for development practitioners to keep up with tomorrow’s opportunities and risks. Even for more technologically sophisticated members of the community, the focus on technology often overlooks hardware and exclusively focuses on software. As we begin 2020, I wanted to share the five trends in hardware that I think international development stakeholders—implementers, policymakers, civil society, the private sector, and others—should be watching for changes in the near term.

The Five Trends

1. TinyML. Machine learning frameworks that allow implementers to train a computer model based on example conclusions from a set of training data are making profound impacts on the way we will use computers. This may sound like a software trend, but the reality is these models need to run on hardware in order to apply them to real-world problems. Until recently, that meant most of the models lived in the cloud.

Over the last few months, however, we have seen the explosion of tinyML—frameworks that allow for those models, once trained, to run on very common, low-cost, and low-power hardware. While tinyML is so new it doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page (as of this writing at least!), we can expect to see commercial products and small-scale projects using these frameworks very soon. Development stakeholders will need to quickly become conversant about the opportunities and risks associated with artificial intelligence, especially as it becomes available everywhere.

2. LPWAN. The lack of tweeting refrigerators in coverage of this year’s Consumer Electronics Show is evidence that the Internet of Things (IoT) has reached a more mature phase of the hype cycle and the nontrivial problem of actually connecting all those things to the Internet has come into greater focus. We want our Things to be inexpensive and to be able to last months or years on a battery, and on these metrics existing technologies like wifi and GSM fall short. A new generation of low-power wide area network (LPWAN) technologies is vying for dominance. LoRaWAN, built on the proprietary LoRa wireless protocol, attracted a lot of early interest and remains promising. But we at DAI have not been the only implementers to be a little disappointed with our field trials of the tech. Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT), on the other hand, seems worth a look. It builds on existing 3G infrastructure which can be useful in many developing countries. Yet, with so many existing installations of connected sensors being involuntarily ripped up because of the phase-out of 2G right now, it might be a hard sell.

Choices related to the buildout of the infrastructure—in terms of both wireless networks and data flow—for these technologies will have far-reaching implications for smart cities, Industry 4.0, and other promising applications. Developing countries have both more to gain from enabling the right choices and more to lose from making poor ones than their western counterparts.

3. Open-source silicon. The instruction set architectures (ISAs) that dictate how microprocessors perform operations on data are complex and, until recently, almost entirely proprietary. ISA development is hard, and so while very large companies such as Intel and AMD can afford to produce their own ISAs for many of their products, most other vendors license intellectual property (IP) from companies such as Arm Holdings. In either case, the need for an ISA represents a barrier to entry to producing silicon.

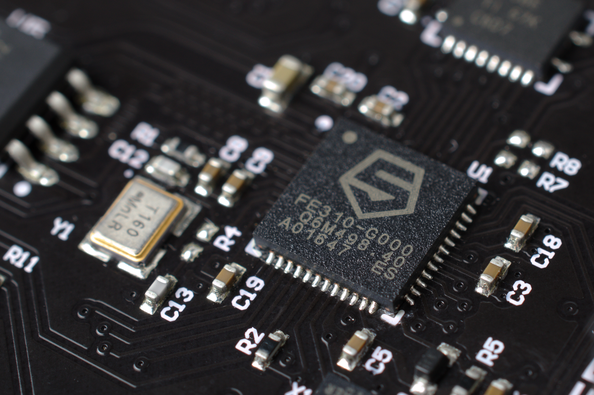

But this is changing: an open-source ISA project called RISC-V matured such that it is now feasible to produce commercial microcontrollers based on the architecture. At least partially in response to this, longstanding industry player Wave Computing has open sourced a current version of the venerable MIPS ISA.

A RISC-V development board from SiFive. Picture taken by Gareth Halfacree.

The availability of open source architectures such as RISC-V and MIPS mean that traditional producers can fashion silicon without developing their own ISAs or remitting licensing fees to companies like Arm, have the flexibility to customize those architectures without legal constraint. Using a component called a field-programmable gate array or FPGA, which can be thought of as a user-configured silicon chip, royalty-free designs can be created cost effectively in almost any quantity without having to actually manufacture silicon.

The advent of open-source toolchains has historically led to a flowering of novel applications from nontraditional technologists, and open-source silicon will likely be no different. We may see novel ISA applications, a multifurcation of silicon design traditions, or the growth of silicon industries in developing countries. With open source ISAs and FPGA toolchains that are themselves going open source and getting easier to use, we may well see changes in the way FPGAs are used. It all adds up to more options for applying cutting edge technology to problems in more contexts.

4. BVLOS. We all are aware of the hype around drones and how they will change the world, and in infrastructure-poor parts of the world, the promise has been especially intriguing. But while drones have brought dramatic changes to certain sectors—infrastructure inspection, for example, is done vastly differently than it was 10 years ago—by and large, the science fictional scenarios remain on the page.

That might change with a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking released by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in December that defines a system for remote identification of drones. Why does a proposed rule for how drones are used in U.S. airspace impact developing countries?

In North America and Europe, drone operators are restricted from flying beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS). The FAA’s rules are intended to put into place an infrastructure that will make it safe to lift those restrictions. The proposed regulations, which would take full effect three years after being imposed, do not themselves allow BVLOS, but will clear the way for new rules that will. While having no legal force outside the United States, these regulatory changes will affect the drone equipment available on the commercial market worldwide. As a result, expect to see the global landscape of possibilities (and problems) expand dramatically for drones around 2023.

Relativity Space 3-D printer driving space launch costs down through 3-D printed engines. Image taken by Relativity Space.

5. Space. With launch costs dropping sharply, and approaches to developing satellites changing dramatically, there can be few domains experiencing more change in 2020 than space. Few development implementers are going to launch their own satellites (though it is no longer inconceivable), but the availability of new tools that this will enable will bring opportunities for international development. From SpaceX’s global internet venture Starlink to Planet Labs’ offer of imagery of every meter of earth every day to low-cost globe-spanning IoT services like Lacuna Space, we are already seeing offerings that could affect change in developing countries and change the way implementers operate.

All these trends are worth watching. Stay tuned for more blogs in 2020 on these topics.