Overcoming Gender Biases to Support Cyber Workforce Development in North Macedonia

Apr 4, 2024

In my country of North Macedonia and elsewhere, cyberattacks on our essential services are becoming increasingly multifaceted and intricate. To defend against them, diverse teams equipped with myriad perspectives are key to comprehensive cybersecurity problem solving. This diversity, however, does not exist in the cybersecurity field; women—who represent half of technology users—comprise only 25 percent of the global cybersecurity workforce and only 11 percent of information security jobs among the European Union’s operators of essential services and digital service providers.

This disparity is concerning both as a matter of equity and security. A homogeneous workforce limits national capacity for cybersecurity problem solving. Furthermore, the underrepresentation of women in cyber career and academic pathways perpetuates gender stereotypes and may sway females from pursuing these pathways. When young women and girls see a field dominated by one sex, it can unconsciously reinforce outdated beliefs about what they can or cannot achieve. This stunts the growth of countries’ cybersecurity workforces by narrowing the talent pool.

Built-in Social Biases at an Early Age

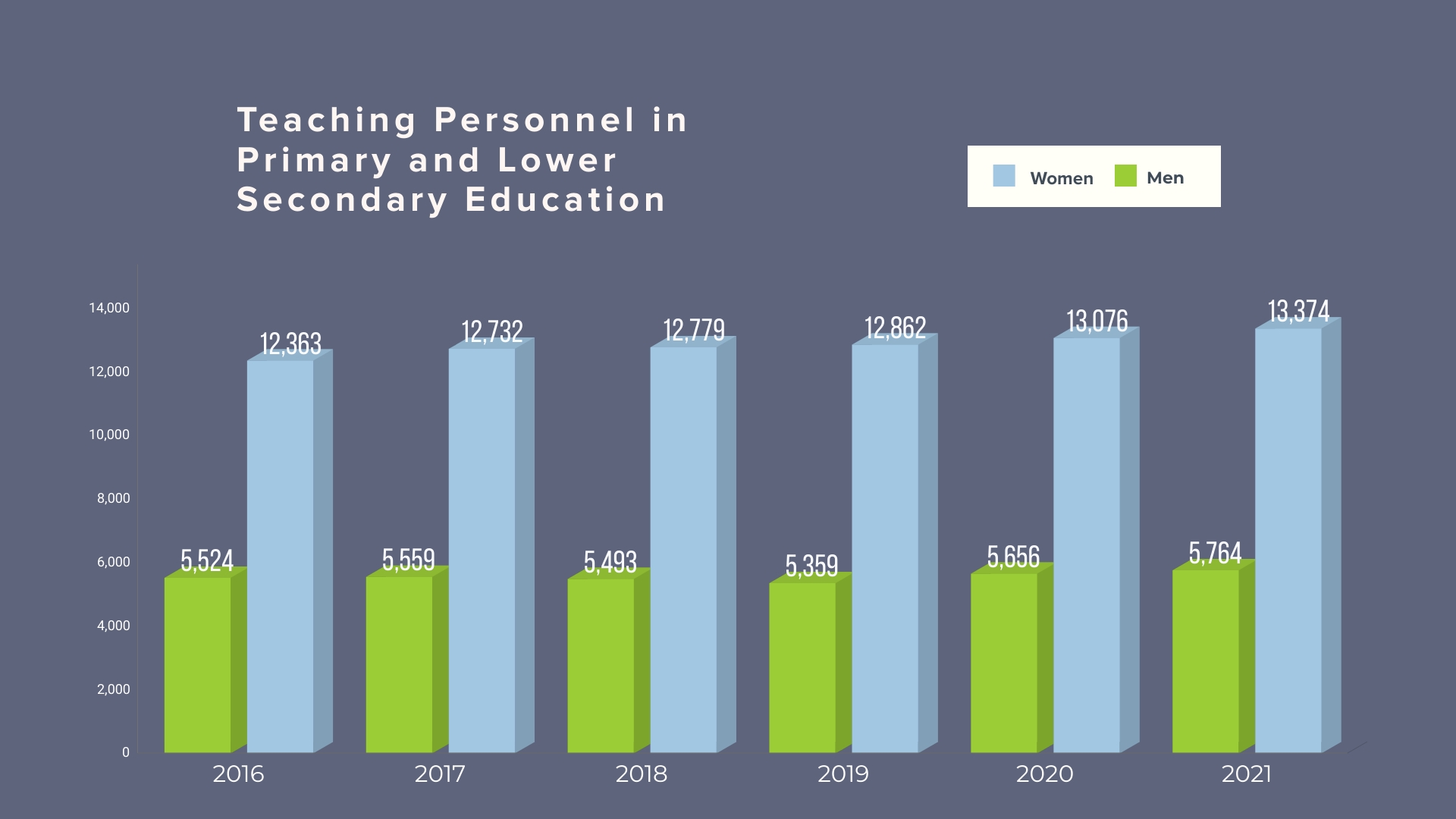

A pervasive narrative is present in North Macedonia from an early age for young girls. Teaching in primary and lower secondary schools, for example, is seen as ideal for women and young mothers as a career that would harmoniously blend with the responsibilities of managing a home and nurturing a family. Many young girls and women from my generation and those who have followed have been subtly—and sometimes not-so-subtly—directed toward careers viewed as “suitable” for women. We women continue to encounter these persistent social biases.

Source: State Statistical Office of the Republic of North Macedonia (October 2023)

Today’s shortage of women in cybersecurity can be addressed in part by motivating more girls and women to pursue this profession and more institutions—starting with schools—to help build these career pathways. For girls in North Macedonia, the road from childhood to a career in cybersecurity contains many impediments; today, the Cyber Pathways for Women (CPW) activity is confronting these obstacles. CPW is an activity of Critical Infrastructure Digitalization and Resilience (CIDR), a regional program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development to develop cybersecurity in the Western Balkans, Black Sea region, and South Caucasus, and led by DAI.

Perceptions Steer Girls and Women Away from Cybersecurity

In North Macedonia, social norms influence children’s choices of educational fields and directly contribute to gender segregation within the labor market. In the 2020–2021 academic year, 65 percent of students enrolled in gymnasium (general high school) were girls, as were 73 percent of pupils studying health. On the other hand, in the more technical academic tracks, 68 percent of students studying agriculture and veterinary medicine, 95 percent studying mechanical engineering, and 85 percent studying electrical engineering were boys, according to UN Women. Several surveys also indicate girls across North Macedonia may already have lower confidence in their digital skills than boys by age 15. In fact, when girls in primary school perform well in both STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and humanities (non-STEM subjects), girls tend to choose a humanities schedule for high school because they believe it will be easier for them to achieve higher grades.

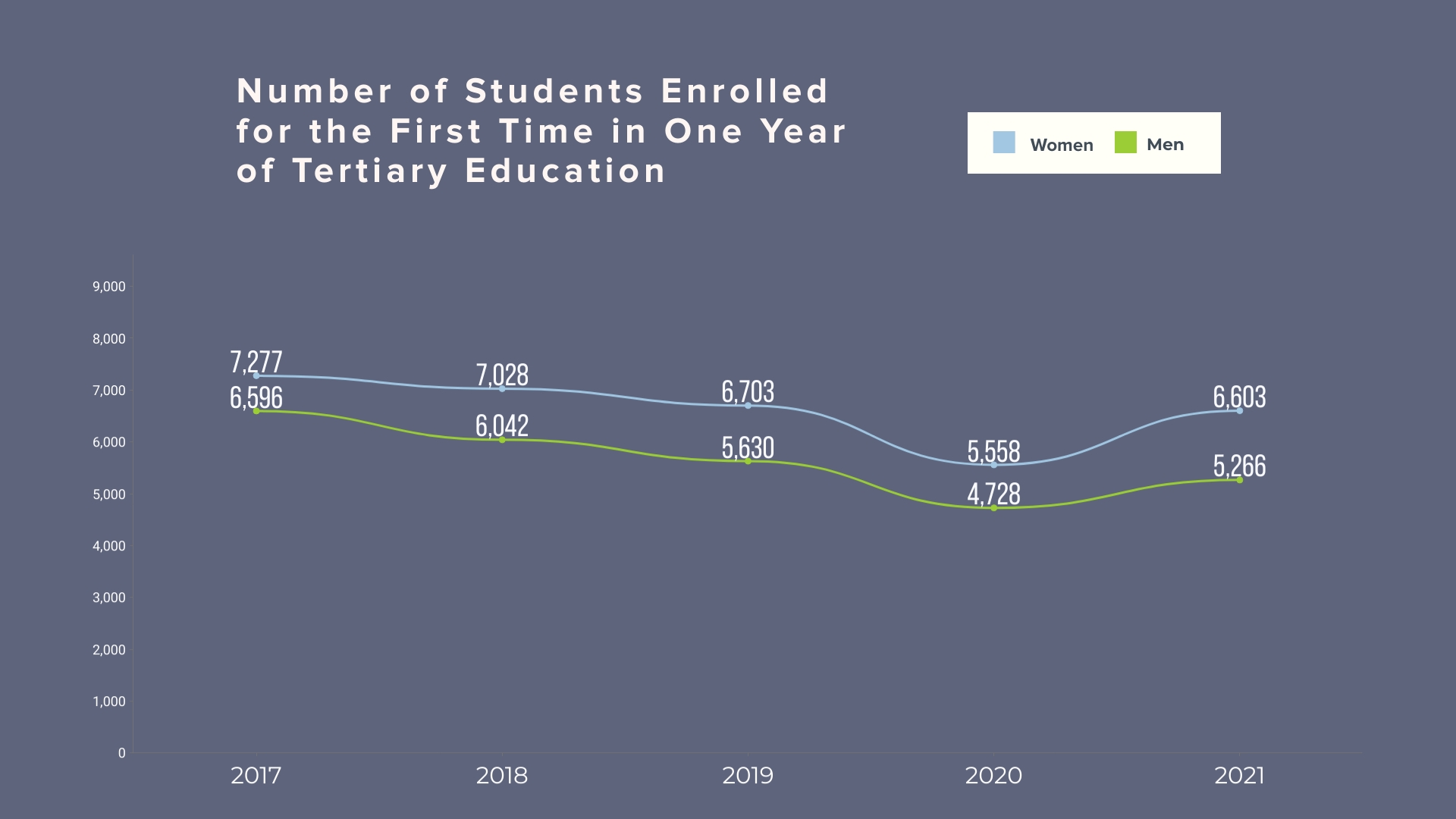

Source: State Statistical Office of the Republic of North Macedonia (October 2023)

Despite the increasing enrollment of young women in tertiary education (see chart above), a concerning trend emerges as we lose women’s participation in the labor force after they complete their degrees. This often occurs when young women either prioritize starting a family or opt for jobs that ensure their sustenance and family support.

STEM education is an area ready for change in traditional gender roles. Long before the pandemic began, the demand for digital skills across Eastern Partnership and Western Balkan countries was prompting curriculum overhauls; these countries include Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Ukraine. As schools in these countries evolve by incorporating digital literacy and 21st-century skill-building into coursework, education ministries must ensure that girls benefit equally, according to the International Telecommunication Union. This stance is consistent with USAID’s Youth in Development Policy, which calls for creating the services, opportunities, and support that all young people need to develop in healthy ways.

In the face of these curriculum overhauls, North Macedonia is grappling with misunderstandings regarding gender equality and witnessing the propagation of gender misinformation. This was notably evident in the capital of Skopje in June 2023 when several thousand protesters denounced the Draft Law on Gender Equality and amendments to the Law on Civil Registry as threatening traditional ideology. Within this context, CPW is conducting activities to attract women and girls into ICT- and cybersecurity-related career and academic pathways.

Playing a cybersecurity board game at the Safer Internet Day event in Skopje. Photo: Ivan Popovic.

Normalizing Cyber Pathways for Women and Girls

CPW recently launched two task forces in North Macedonia—the STEM Teachers Task Force focused on primary and secondary education and the Academia Task Force for university technology professors. These aim to attract more girls and women into the cybersecurity academic pipeline.

CPW launched these task forces at events in October and December 2023 with approximately 40 total stakeholders, and both events produced encouraging takeaways, including:

- There is strong interest and need across North Macedonia’s education sector to bolster female participation in academic tracks relevant to cybersecurity.

- Female role models can help motivate females’ interest and participation in cyber-related academics.

- Task force members can help build the linkages (pathways) between cyber-aspirant females and employers seeking trained and qualified job applicants.

Both task forces will convene regularly this year to plan and implement actions to support the building of cyber pathways from childhood to the job market. This will include by utilizing CPW’s baseline research and stakeholder mapping to strategically engage decision makers in the cybersecurity workforce, develop gender-inclusive curricula, establish mentorships, launch behavior change campaigns for parents and communities, and facilitate dialogue on creating inclusive policies, including ones to address gender-based harassment and violence, an area in which young women and families have shown particular interest.

For example, as part of our Safer Internet Day event, CPW and the STEM Teachers Task Force brought together young students and cyber women champions at the Creative Center Karposh, an extracurricular learning center in Skopje for motivated students and teachers. The students and champions met face to face in a session titled “Meet the Professional.” As a CPW manager, I felt rewarded to see how we matched the secondary school students and women professionals from different cyber-related organizations. This activity offered female students a unique opportunity to interact with women cyber professionals from various cybersecurity domains and ask questions about their working pathways and challenges.

I believe that through this initiative, we inspired young girls to consider cyber-workforce career paths by providing a closer look at what they can anticipate. Additionally, we were honored at this event to host U.S. Ambassador to North Macedonia Angela P. Aggeler, which was a thrill for the students and everyone in attendance.

U.S. Ambassador to North Macedonia Angela P. Aggeler and students at the Safer Internet Day event in Skopje. Photo: Ivan Popovic.

While women and girls face many impediments to entering cybersecurity career pathways, these barriers are surmountable; in fact, it is good business for employers of all kinds—academic, government, private sector, critical infrastructure—to help break down these barriers to grow their respective pools for qualified cybersecurity job candidates.

In addition to North Macedonia, CPW operates under the CIDR program in Serbia and has recently begun planning activities for Moldova. Each country’s activities aim to help develop well-prepared women, more informed and supportive influencers and decision makers, and, ultimately, stronger cybersecurity workforces for protecting our essential services.

For the rising generation, a good place to start this development is by breaking through the glass ceilings at our schools. The need is apparent—for example, in a 2023 CIDR survey of North Macedonia’s public institutions, 87 percent of respondents said they do not have enough skilled cybersecurity personnel at their institution.

My country has a great opportunity to build its cybersecurity talent pool by expanding technology-focused academics to those whose technology potential has been underutilized. By growing the number of girls and young women entering and taking ICT- and cybersecurity-related coursework, North Macedonia will be helping to address the long-term demand of employers for qualified professionals who can secure their organizations from cyberattacks.

DAI’s Liljana Pecova Ilieska is the manager of the Critical Infrastructure Digitalization and Resilience program’s Cyber Pathways for Women activity in North Macedonia.